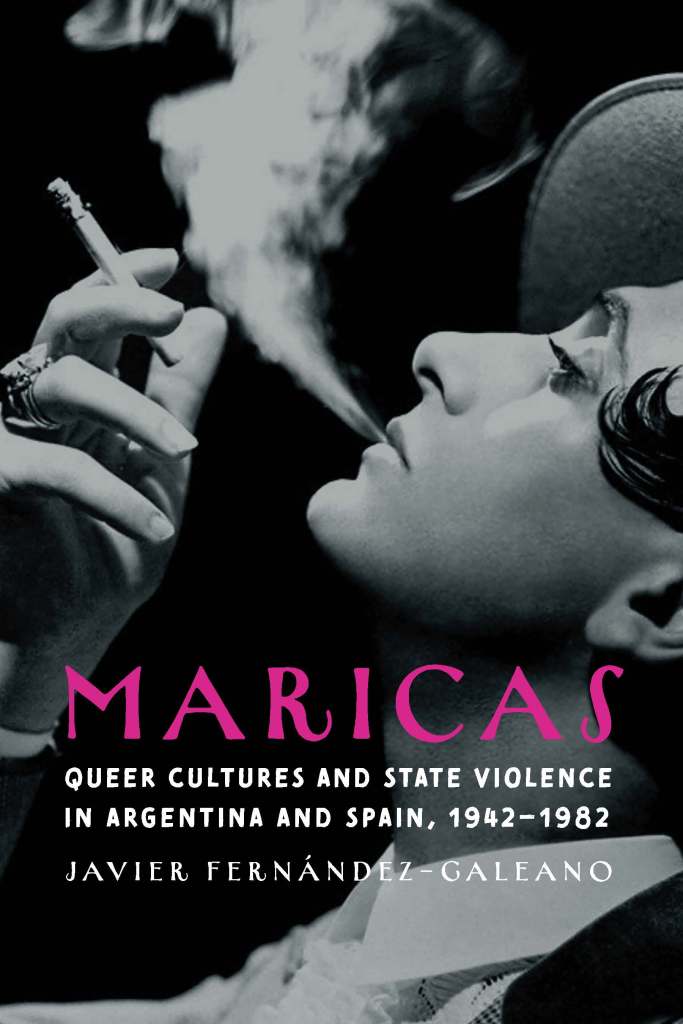

Javier Fernández-Galeano is a Ramón y Cajal Fellow at the University of València. His most recent book is Maricas: Queer Cultures and State Violence in Argentina and Spain, 1942–1982, which was published by Nebraska this month.

Maricas traces the erotic lives and legal battles of Argentine and Spanish gender- and sexually nonconforming people who carved out their own spaces in metropolitan and rural cultures between the 1940s and the 1980s. In both countries, agents of the state, judiciary, and medical communities employed “social danger” theory to measure individuals’ latent criminality, conflating sexual and gender nonconformity with legal transgression.

Argentine and Spanish queer and trans communities rejected this mode of external categorization. Drawing on Catholicism and camp cultures that stretched across the Atlantic, these communities constructed alternative models of identification that remediated state repression and sexual violence through the pursuit of the sublime, be it erotic, religious, or cultural. In this pursuit they drew ideological and iconographic material from the very institutions that were most antagonistic to their existence, including the Catholic Church, the military, and reactionary mass media. Maricas incorporates non-elite actors, including working-class and rural populations, recruits, prisoners, folk music fans, and defendants’ mothers, among others. The first English-language monograph on the history of twentieth-century state policies and queer cultures in Argentina and Spain, Maricas demonstrates the many ways queer communities and individuals in Argentina and Spain fought against violence, rejected pathologization, and contested imposed, denigrating categorization.

Introduction

Marica Politics?

This book argues that queer and trans genealogies ought to incorporate marica archives like Hugo’s oral history, collected by Archivos Desviados. Hugo (1943–2020) aptly traces how marica cultural codes informed the genesis of the (homo)sexual emancipation movement. Mir Yarfitz and I have argued elsewhere that marica historically referred to “subjects assigned male at birth who adopted a feminized persona through sexual practices, embodied and spoken languages, and social interactions, including relationships with masculine men, situational gender switching, and subcultural codes.” Hugo’s testimony fits this definition, but by that I do not mean to put the burden of representativeness on it. Hugo was born in Caballito, a neighborhood of Buenos Aires. He and his friends alternated between he/him and she/her pronouns (which I will replicate in my writing about them). Since his early childhood, she occasionally dressed like a woman—using sheets for a long dress à la Evita Perón and makeup stolen from his mother. As an altar boy in the parish church, he and one of his peers secretly imitated vedettes in the church gardens, turning leaves into feathers. Sexual abuse by the priests tarnishes these memories. It was only by meeting other maricas when he was an adolescent that she discovered the joy (alegría) of togetherness, a “marvelous awakening” (despertar maravilloso) despite social scorn and police harassment.

He started to frequent downtown cruising spots, including cinemas, public restrooms, and the Augustus bakery, which she describes as maricas’ own cathedral, “a swarm of locas.” In between sexual encounters, maricas turned Augustus into a sort of “cultural center”: they shared information on recent police raids and discussed poetry, art, and movies (like the 1964 Argentine premiere of Las amistades particulares, an adaptation of its namesake novel by Roger Peyrefitte). Hugo was “catechized” in marica codes by his new kin. Carnival and its preparations—like sewing dresses—were crucial components of marica sociability, since maricas’ cross-dressing became an object of popular celebration during that time of the year. During the day, Hugo worked for an insurance company. When the workday was over, she put on her makeup, met a marica friend, and together they cruised for sex downtown while singing flamenco and praying to the Virgin Mary when young boys (chongos) harassed and insulted them. Spanish dancing companies (las locas españolas) performed at the Avenida theater, a landmark for Buenos Aires maricas: “We all identified with flamenco, with gypsies’ lament, because it was like our marica lament.” Anti-marica police harassment was constant. Hugo was once tortured by police officers, who called themselves machos while hitting metal against metal above Hugo’s head. Hugo also spent several days in the Devoto Prison in the early 1960s, having a passionate love affair with another prisoner whom she met in the weekly mass and using their hands to communicate without words through the cell bars. When President Juan Domingo Perón died in 1974, his followers flooded Buenos Aires downtown to mourn him, and this became an orgiastic opportunity for maricas like Hugo, who seduced and had sex with plenty of Peronist chongos.

In the early 1970s, Hugo and one of her friends founded a camp order of “impure” nuns. They requested and were granted permission to live in the monastery of San Camilo and later the convent of Santa Inés, turning their own dormitories into a marica/queer convent, until they were expelled for bringing chongos into the convent and having sex with them at night. In 1973, Hugo ran into a street protest staged by Eros, the section of the Frente de Liberación Homosexual (Homosexual Liberation Front, or FLH) led by Néstor Perlongher, and asked them how she could become part of their movement. Hugo remembers fondly the role that Héctor Anabitarte’s political guidance and affection played in his own process of self-empowerment. The formation of the Catholic homosexuals’ group within the FLH was Anabitarte’s idea. One of the most joyful moments in Hugo’s memory is the founding of Somos (the FLH’s publication). To celebrate the consensus they had reached on the publication’s name, they drank and smoked marijuana, danced, and cracked jokes while Hugo sang cuplés popularized by Spanish singer Sara Montiel, sharing an “unforgettable feeling of freedom and hope.”

However, Hugo also relates how some FLH activists (the group Profesionales) despised maricas and afeminados (feminine males) like Hugo because, in their opinion, maricas’ scandalous personas and habit of cruising for sex antagonized potential adherents. Hugo counterargues with juxtaposition: there were activists who had lost “the poetry of being a homosexual” for the sake of maintaining hyperintellectualized views, and there were maricas who put their bodies on the line, demanded respect, and did not want to be objects of study. After the parenthesis of the last dictatorship, Hugo reassumed his LGBTQ activism and commitment with the left, being aware of the postdictatorial regimes’ flaws—“democracy was heterosexual,” he said. Fear of police and his own family repeatedly led him to destroy his own compromising belongings during the last dictatorship, including Anabitarte’s papers. In view of this forced erasure of his own archive, Hugo warns that taking care of our “struggle” entails remembering our marica ancestors. Hugo, like many of this book’s protagonists, treated marica subjecthood as transcendent while simultaneously parodying transcendence as a camp artifact.

I grew up a sheltered mariquita—feminine, sensitive, and familial, even Catholic—in Badajoz, a municipality in the region of Extremadura, which many Spanish people associate with rural culture. My deepest fear was to be called a maricón—despised as hypersexual and feminized—and instead I ended up identifying as gay, a comparatively easy-to-pronounce word that often works to deactivate prejudices by referencing mainstream paradigms. The term “homosexuality” feels unfamiliar to me, too full of fricative sounds, as if pronouncing it entails the intentionality of marking someone as something other than. I only learned to use “queer” as a graduate student—it is not originally a Spanish term—and while I use it in communication with English speakers, it never crosses my mind when I think of maricas’ pleasures or experience them. Yet since this book is written in English—which could merit a longer discussion on the international structures of academic knowledge production—I am going to use “queer” as a verb more than as a noun in reference to sociocultural practices that unsettle normative regimes.