Venetia Hobson Lewis worked at several stock brokerages and for almost eighteen years as a corporate paralegal for a motion picture studio. She is the author of several award-winning Western short stories. Her newest book, Changing Woman: A Novel of the Camp Grant Massacre, was published this month.

Arizona Territory, 1871.

After men from Tucson massacred 150 Apache women near Camp Grant, what did their wives in town say and do about it?

Changing Woman: A Novel of the Camp Grant Massacre, a historical fiction novel, answers that question. Two fictional heroines—Valeria Obregón, a Hispanic, and Nest Feather, a young Apache girl abducted at the massacre—sort out the truths and the lies. They relate with real historical personages, who recreate the events of their lives, as found in historical texts, primary documents, and memoires.

Most of the experiences of pioneer women have been overlooked, ignored, and lost to history. As novelist, I attempt in Changing Woman to give voice to those women’s stories, recreate the tense atmosphere in Tucson as they went along their daily lives, and share their possible varying responses to the massacre.

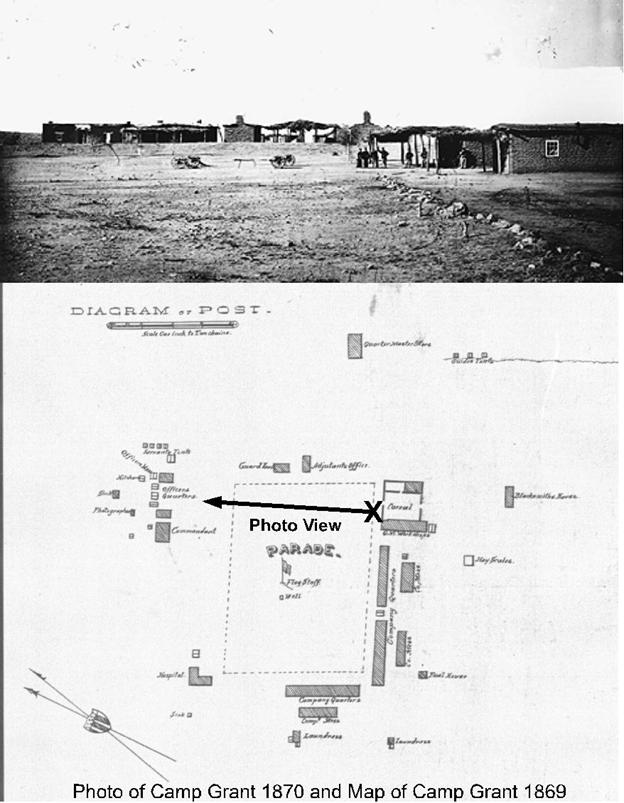

“The blackest day in Arizona history,” April 30, 1871, dawned in Aravaipa Canyon with the slaughter of Apache women by a murderous band of Anglo, Mexican, and Papago men from the Tucson area, fifty-five miles to the south. Camp Grant—branded by John O. Bourke as “the most thoroughly God-forsaken post”—slumbered, totally unaware of the carnage going on five miles to the east.

An acrimonious triangle—comprised by the United States military, the residents of Arizona Territory, and the warring Apaches—resulted in the massacre. Posted at camps throughout the territory for the safety of the territory’s citizens, soldiers regularly went on scouting expeditions to subdue the Apaches, whose raiding of residents’ ranches and homes necessitated the military presence, which provided the citizens with an economic opportunity to make money by supplying the military with supplies and goods. However, the people of Arizona Territory constantly complained that the military failed to provide enough protection. This internecine struggle permeated the territory’s existence in 1871.

No one was immune from the sting of Apache attacks. Ranchers and farmers in the outlying areas never went to their fields without arms. A sizeable number of men never returned home from their toils. Mail riders lost their lives while carrying bundles of letters from station to station. Frequent cattle raids mounted to great losses for the ranchers, who along with the townspeople of Tucson, met in nightly meetings at the courthouse to come up with a solution.

By necessity, many Tucsonans became experienced Indian fighters. Quite a few, including the Territory’s governor, suggested that these experienced citizens should assist the military in subduing the warring Apaches—particularly the Aravaipa Apaches, whom Tucson’s citizens indentified as being particularly vicious under the leadership of Eskiminzin.

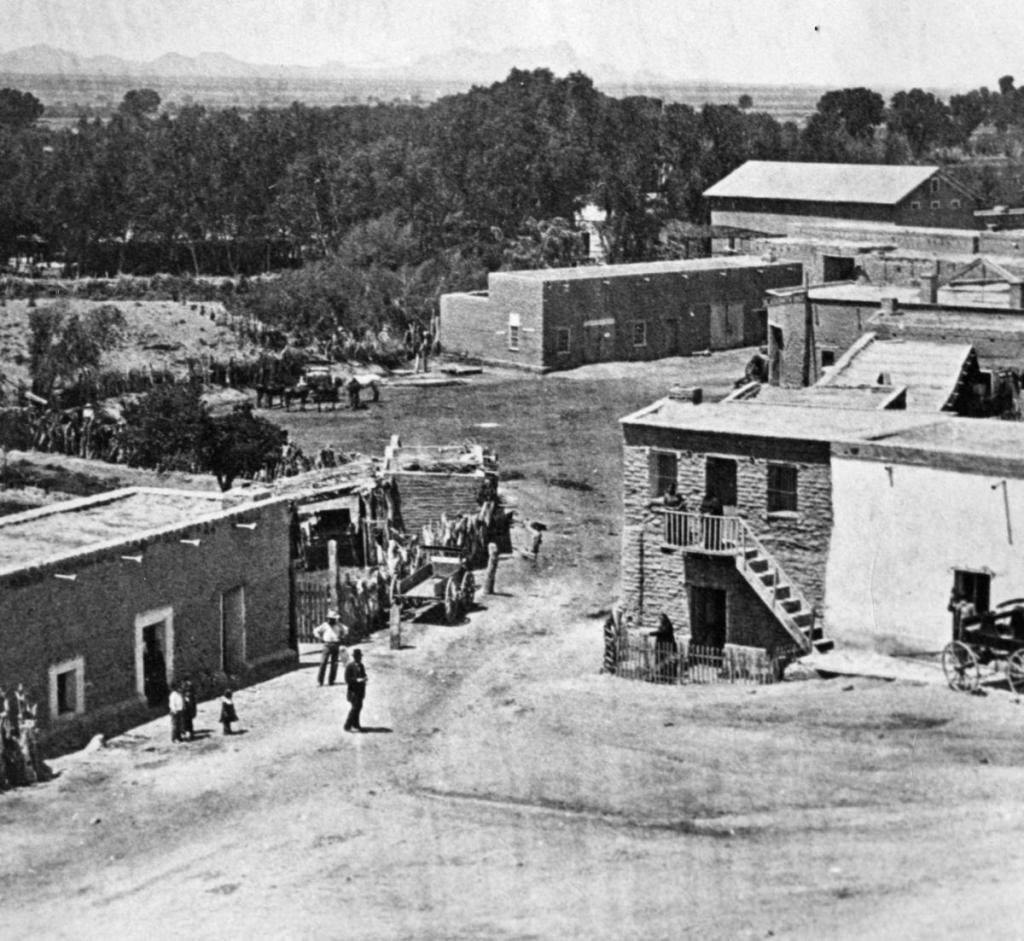

In 1871, Tucson’s 3,000 residents only reluctantly left the relative security of the town. The majority of women centered their lives around family, home, and church. Seven Sisters of St. Joseph of Carondelet arrived in Tucson in 1870 and quickly established a school of meritorious standards and acclaim. Some women became entrepreneurs: shop owners, seamstresses, restaurant owners, teachers, and madams.

Early on in my research of the Camp Grant Massacre, I realized there weren’t many written statements or opinions by Tucson’s women about their lives or the raid. Atanacia Hughes, the wife of the territory’s adjutant general who supplied arms to the perpetrators from their home’s dining room, was quoted that she supported everything her husband did. Besides her accommodating encouragement, she left few statements.

The slaughter of 150 Apache women most assuredly must have created varying opinions: disbelief, support, concern, relief, abhorrence. After the attack was known, there had to have been conversations in ladies’ social clubs or at dinner tables or in bed with husbands who participated in the massacre.

From Charles Etchells’s Hayden file at the Arizona Historical Society came the recounting that every time the massacre was brought up in conversation at his house, Etchells would hang his head and never utter a word. But Soledad, later his wife, would brightly comment, “Charlie went. Didn’t you, Charlie?” I could envision that she smiled sarcastically and poked him in the arm. Reading that entry, I knew I had to have a scene with Soledad.

Other women’s voices were more elusive. So I began to wonder, what would I think and how would I react to such news? The Anglo and Mexican perpetrators from Tucson talked about their raid the first few days after the attack, and then they all agreed not to talk about it at all. They silenced themselves. How did wives deal with silence? That would make many women very curious. Maybe they invented excuses for their men. Or the men provided excuses or lies about their actions to their wives. Most likely all of the above.

As the church filled a major part of people’s lives, I read about the sisters of Carondelet. Sister Monica had been married, but lost her entire family to diphtheria. Her voice would be compassionate. Remembering a friend’s recounting of the stern nuns at her catholic school, I determined that Mother Emmerentia’s voice should be commanding, perhaps even a bit brittle.

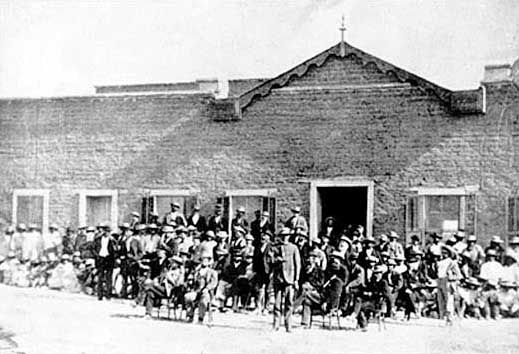

Upon hearing of the massacre, Quakers and other religious persons on America’s east coast immediately called for retribution. For some time they had been solicitous of their plan to tame Indian tribes by immersing them in Christianity. At the end of the year 1871, a trial ensued.

However, did a trial really end the strife among the bitter triangle? Did the women in Tucson accept their beloved husbands’ actions as justified? I believe my novel comes to several conclusions. As a reader, you may discover a different view within Changing Woman.

To sign-up for Venetia’s monthly newsletter about Arizona’s historical facts and places, visit her website https://www.venetiahobsonlewis.com or email her at venetia@venetiahobsonlewis.me.

Looking forward to reading… The CGM is often forgotten. The viewpoint of the woman impacted even more so. Thank you UNP for publishing this book, and thanks for writing this book, Venetia Hobson Lewis!

Ross Whitman Blair (great great grandson of Lt. Royal Whitman, 3rd Cav, US Army)