Hilary Zaid is the author of the award-winning novel Paper is White. Her short works have appeared in Mother Jones, Ecotone, Day One, Southwest Review, and Utne Reader, and have been twice nominated for the Pushcart Prize. Her newest book, Forget I Told You This, is the first title in the Zero Street Fiction Series and will be published in September 2023. It is available for pre-order now.

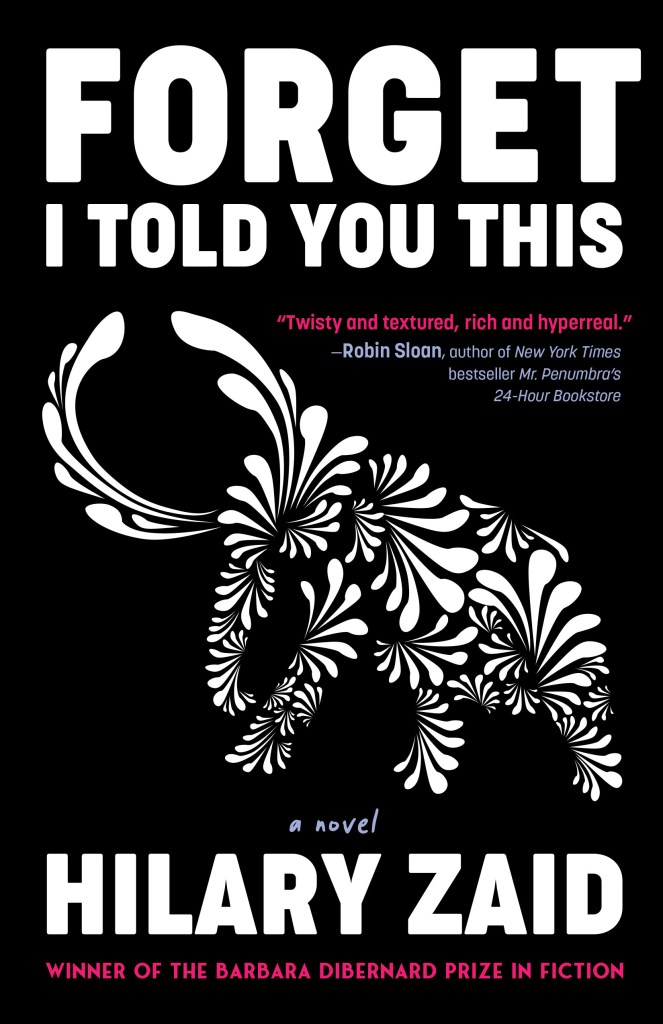

Very early one late winter morning last year, I got on a flight to San Diego and powered off my phone. When dawn broke and the wheels touched down at Lindbergh Field, I powered it back up to a very enthusiastic e-mail from writer and series editor Timothy Schaffert, inviting my novel, Forget I Told You This, to be the inaugural title in the new, queer imprint of the University of Nebraska Press, Zero Street Fiction. “We’d love to take on this project,” Timothy wrote of my novel, a literary thriller about a queer, Jewish artist at midlife who finds herself in the crosshairs of a plot to destroy the world’s largest social media company. “The more I read, the more I loved it. And the writing is just exquisite.”

I can’t think of a writer who doesn’t long to receive an offer of publication – or effusive praise for their work. Exquisite? Me? I’d submitted my novel just a few months before when I spotted the call for manuscripts for a new, LGBTQ imprint launched with the promise of bringing to a trade audience books that have traditionally been marginalized, or not published at all. Having debuted my first novel, Paper is White, with a tiny, lesbian feminist press, I knew what literary marginalization looked like (minimal reviews; condescending glances from bookstore staff), and I yearned for something more. There were only a couple of details, Timothy explained, some edits from himself and the other series editor, writer SJ Sindu. “Our notes are nothing major… just some clarifying, and another layer of polish here and there, etc.”

It wasn’t until I’d signed on whole hog and Timothy and I finally met via Zoom for our editorial meeting that I learned what one of those details was: the plot point on which my narrator’s motivation depended. “It just feels like a distraction,” Timothy said, as calm and reasonable as someone explaining that you might feel better if you took the stick out of your eye. I nodded, feeling neither calm nor reasonable as I saw the entire mechanism of my plot fall to pieces. What would force my narrator to decide what to do if she didn’t discover a hidden family secret? Timothy’s “distraction” was my lifeline! I could hardly breathe.

Timothy listened patiently as I flailed like roped steer to escape this new editorial constraint – over the rest of the call, and via email for the rest of the weekend. He (and his husband) were generous with suggestions: What about an anonymous threat mixed in with the flowers? What about murder? But what kept coming back to me were Timothy’s appreciative comments about what he identified as the core of the manuscript: the desire to make art, the anonymity of the medieval scribe, the longevity of the manuscript, long after the scribe is gone.

After a few days spent flailing against Timothy’s advice, I got to work. I cut the deeply buried family secret. I didn’t need it. It was extrinsic to the story. And what I needed to do—what Timothy’s patient editorial direction enabled me to do—was make the story more intrinsic to itself. That’s the best outcome any editorial feedback can achieve, I think. And, it occurs to me, it is the Queer project of the late 20th and early 21st century: to become more intrinsic to who you always were, all along.

After 50-plus years of an LGBTQ civil rights movement, Zero Street Fiction remains a necessary project. In fact, in light of the regressive new hate directed at queer people and queer books, it may be a more necessary project than ever. It’s a strange thing, writing very contemporary fiction. You never know what will shift under your feet. Writing a book about social media and surveillance capitalism, I had assumed that the social media and data privacy landscape would change in ways that might make this book feel old at birth. Unfortunately, the data privacy landscape hasn’t changed, and the threats to queer lives and reproductive freedoms have made the concerns of the novel more salient than ever.

If all that suggests that Forget I Told You This is pedantic or grim – it isn’t. It’s just a rollicking but lyrical, queer, Jewish literary thriller waiting to be read in one sitting, trying to capture one moment. I’m delighted to have been invited to offer it as the inaugural title of the Zero Street Fiction series as a work of art that is finally, intrinsically and completely itself.