Rainer F. Buschmann is program chair and a professor of history at California State University, Channel Islands. He is the author of several books, including Iberian Visions of the Pacific Ocean, 1507–1899 and Anthropology’s Global Histories: The Ethnographic Frontier in German New Guinea, 1870–1935. His newest book, Hoarding New Guinea: Writing Colonial Ethnographic Collection Histories for Postcolonial Futures, was published last month.

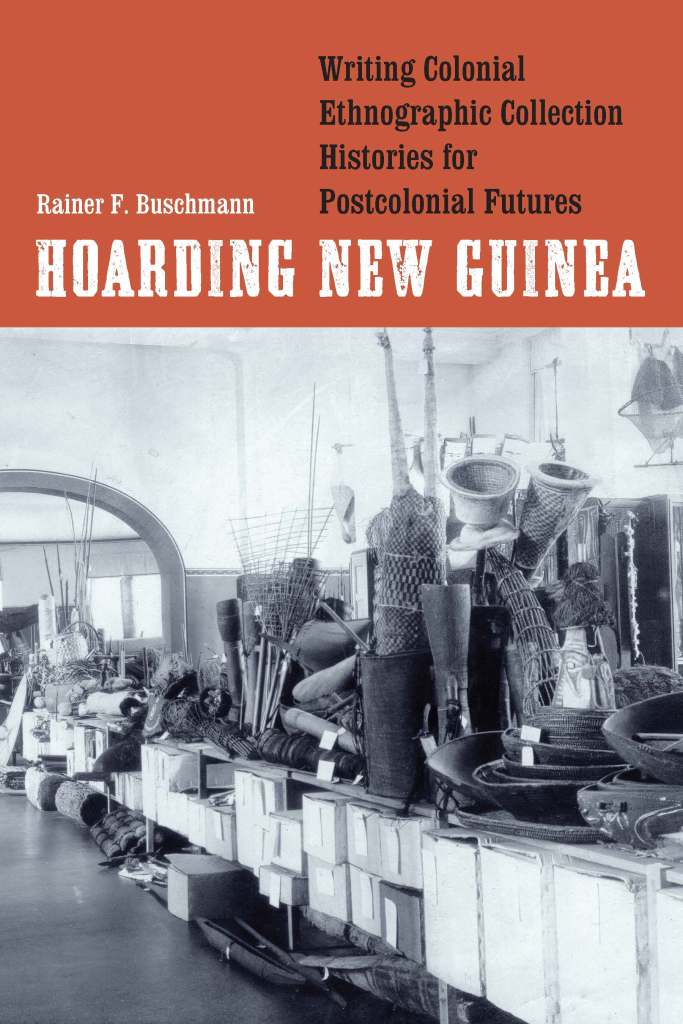

Hoarding New Guinea provides a new cultural history of colonialism that pays close attention to the millions of Indigenous artifacts that serve as witnesses to Europe’s colonial past in ethnographic museums. Rainer F. Buschmann investigates the roughly two hundred thousand artifacts extracted from the colony of German New Guinea from 1870 to 1920. Reversing the typical trajectories that place ethnographic museums at the center of the analysis, he concludes that museum interests in material culture alone cannot account for the large quantities of extracted artifacts.

Introduction

In a now overlooked turn-of-the-century dissertation on population decline in the Pacific Islands, Hans Blum, a former employee of the New Guinea Company, addressed what was a pressing issue for the new German colonies in the region. Blum’s findings were largely unsurprising for a work written during the height of the New Imperialism. Population decline in the area predated European arrival and was connected to the accommodation of the Indigenous seafaring populations to the relative comfort of the island environments, which encouraged such cultural practices as cannibalism, human sacrifice, sexual perversions, and prostitution. Europeans added to this mix alcohol, firearms, and diseases and initiated a disruptive labor trade that exasperated the decline of Indigenous populations. With colonial annexation, the cultured races of Europe were now tasked with bringing civilization to those Indigenous populations that they vowed to protect. It was their duty to curb European excesses, but the colonial government also had to educate the “poor natives” to develop a proper work ethic. Predictably paternalistic both in tone and direction, Blum’s work took an unexpected turn on page 67, where the reader is confronted with an odd-sounding paragraph. In it, Blum urges colonial officials, missionaries, planters, and traders to work closely together in their work to educate the Indigenous populations of German New Guinea. Traders in particular displayed a “lächerliche Kuriositätensucht”—a ridiculous obsession with, or having an addiction to, curiosities (Sucht in German signifies both meanings). The same author thus suggested that the colonial administration should step in to prevent the “unreasonable trade with ethnographica” to chaperon the Indigenous people toward practical work on such profitable natural products as copra, pearls, and shells.

The temporary reversal of carefully crafted colonial hierarchies makes Blum’s “ridiculous curiosities” statement remarkable. The colonizers act irrationally in their craving for Indigenous artifacts, with the colonized seemingly acting rationally in their employment of material culture to explore loopholes in the supposedly airtight colonial system. Blum’s paragraph explores the ambiguities, fluidity, and malleability associated with ethnographic objects. Artifacts make for incomplete, almost faulty commodities, illuminate cracks in the monolith called colonialism, and, perhaps most importantly, reveal Indigenous agentic creativity when bartering or selling artifacts. In short, Blum’s brief passage speaks forcefully to the central themes developed in the current monograph.

I have introduced Blum’s segment because it highlights different ways to engage, study, and display material culture that has been stored in ethnographic museums worldwide for over one hundred years. For the Pacific, the art of New Guinea and its surrounding islands have been an important component. Best known among ethnographic collections are the malagan masks and carvings from New Ireland and the mysterious figures and masks from the Sepik River. Such artifacts attracted both the admiration of nineteenth-century anthropologists who believed they were salvaging material legacies of vanishing cultures and the attention of early twentieth-century artists and poets who sought to propel creative expressions into new realms.

The collections acquired during colonial times entered the postcolonial consciousness when voices demanding the return of Indigenous art to its rightful owners emerged with the independence of African countries throughout the 1960s. However, such restitution demands found themselves blocked by diplomats and museum curators who regarded European museums as the only genuine depositories for the salvage and maintenance of universal cultural heritage. The issue of repatriation of human remains added new dimensions to the restitution of cultural artifacts to former colonies. Especially in Australia, New Zealand, and the United States, where European settlers had significantly displaced Indigenous cultures, the repatriation demands invited additional critiques of ethnographic and other institutions holding human remains.

In 2017 such efforts at restitution and repatriation received support from some unexpected sources. When that year French president Emmanuel Macron made a surprise announcement that his country would endeavor to return to the now independent nations Indigenous artifacts that had been taken out of Africa during his country’s colonial reign, provenance debates reached a wider public. In 2019 Macron encouraged a widely publicized follow-up report on this issue, co-authored by author Felwine Sarr and art historian Bénédicte Savoy, that fully urged the restitution of artifacts to their rightful owner. The authors maintained that Europeans’ colonial regimes of violence made any distinction between objects looted during military operations and those collected by scientific expeditions an impossibility and put museum directors and curators on the defensive.

Across the French border in Germany, controversy arose over constructing a new museum, the Humboldt Forum, in Berlin. This costly project consumed close to $800 million and reconstructed the Prussian palace that East German officials tore down following the Second World War. Apprehension about rising German nationalism expressed in the building of the Humboldt Forum was soon followed by concerns about the collection context of artifacts hailing from the former German colonies in Africa and the Pacific. Critics rightfully feared that the display of such objects would not reference the colonial context, and disapproving voices accompanied the institution throughout its 2020 virtual and 2021 physical opening.