Hanne Nielsen is a senior lecturer in Antarctic law and governance at the University of Tasmania. Her research interests lay in representations of Antarctica, including Antarctica in advertising and Antarctica as a workplace. Nielsen has spent five seasons working as a guide in the Southern Ocean. She co-chairs the steering committee of the Standing Committee of Humanities and Social Sciences for the Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research and is a co-lead of its Tourism Action Group. Her mission is to bring the stories of the Ice to the rest of the world to inspire, engage, and promote care for Antarctica. Her book Brand Antarctica: How Global Consumer Culture Shapes Our Perceptions of the Ice Continent was published this month.

In April 1961 Soviet surgeon Leonid Rogozov fell ill with appendicitis whilst in the Antarctic. As the station doctor his fate was quite literally in his own hands – Rogozov operated on his own abdomen, thereby saving his life, and going down in Antarctic folklore. Following this incident, many National Antarctic Programs required winter expeditioners to have their appendix removed before being deployed. I heard this in passing and thought nothing of it. The story lay dormant, like a seed. Then, when I found myself struck by appendicitis in Vietnam, casting around for one good thing, my brain obliged with the thought: “at least now I can go to Antarctica.” And so it all began.

I first went south with Antarctica New Zealand in 2011, as part of the University of Canterbury’s Postgraduate Certificate in Antarctic Studies. There was a lot of snow and ice, but my interest was in the human stories that are layered over the continent. I was in a place for heroes during the centenary of Robert Falcon Scott’s Terra Nova expedition, talking to climate scientists about threats to Antarctica, and feeling like I was experiencing the place incorrectly somehow because the visit did not feel “life-changing.” Overlapping framings of the place coalesced in an Antarctic encounter that has, in fact, shaped everything since.

Upon my return to New Zealand I took a job with an advertising company. Drinking coffee from my Scott Base mug each morning my mind would wander back – I wanted to find out more about the stories that circulate about this frozen place. Somewhere between writing advertisement copy for tractors and dreaming of the ice, my PhD project was born, asking how Antarctica had been depicted in advertising, and what this meant both for us as humans and for the continent. Once you are looking, the advertisements just keep coming – a penguin here, a hero there, with the odd lost polar bear thrown in for good measure. The project became a thesis and then became a book which highlights the power of Brand Antarctica to inspire and to sell.

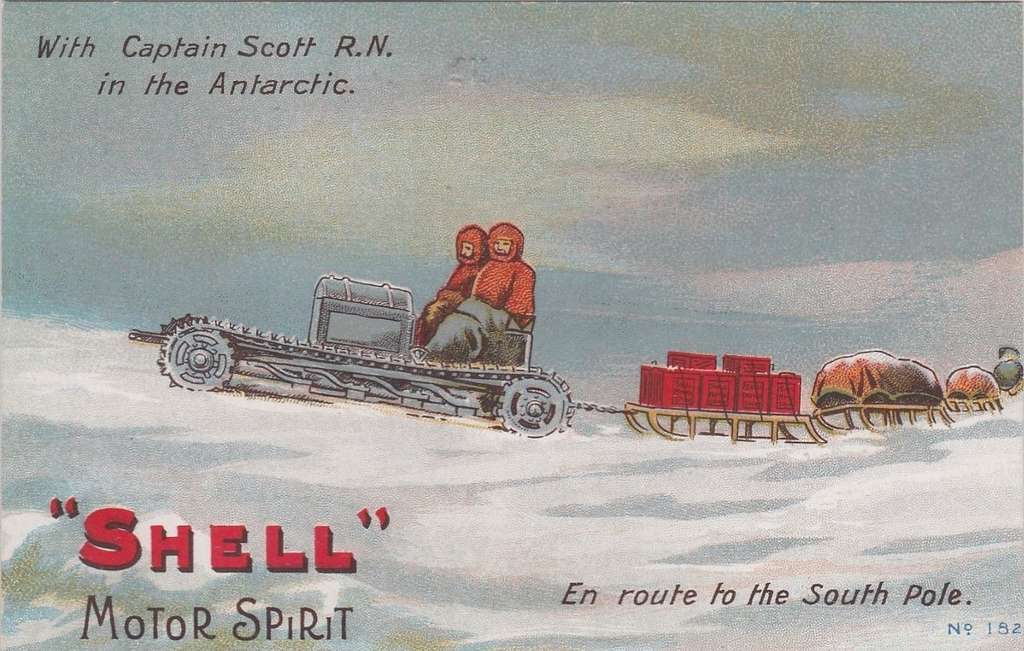

Most people never go to Antarctica, so their ideas about the place are mediated through cultural production – that includes photographs, diaries, narratives, videos, and advertisements. Advertisements are a particularly useful way to understand what Antarctica has meant at different points in time because they recycle ideas that are already in circulation. They also situate Antarctica within a global system of commerce, rather than as a continent apart from the rest of the world.

Throughout Brand Antarctica, I explore five of the most prominent framings of the far south: Antarctica as a place for heroes (including an analysis of the commercial sponsorship of early expeditions); as a place of extremity (where machines allow people to live in an extreme environment); as a place of purity (particularly common in advertisements for products from Antarctica, which play on the continent’s untouched nature); as a place of fragility (cue icy imagery and calls to consumers to adopt environmentally friendly practices); and as a place of transformation (particularly important in the context of growing Antarctic tourism numbers). Together, these framings paint a picture of a continent with a rich history of both human narratives and commercial interest. Ice moves. Perspectives shift. Stories accumulate like snow, year on year.

I wrote this book to better understand how humans have used Antarctica over time – both physically and symbolically. For most readers, the Antarctica they carry around in their heads seems far more real than the ice itself – that was certainly the case for me when my appendix made itself known. Yet Antarctica plays a vital role in many global systems. We need to understand what people think about the place, and why, in order to plan for any future protection. That is why Brand Antarctica, and the cultural framings and the stories we tell about the far south, are so important.