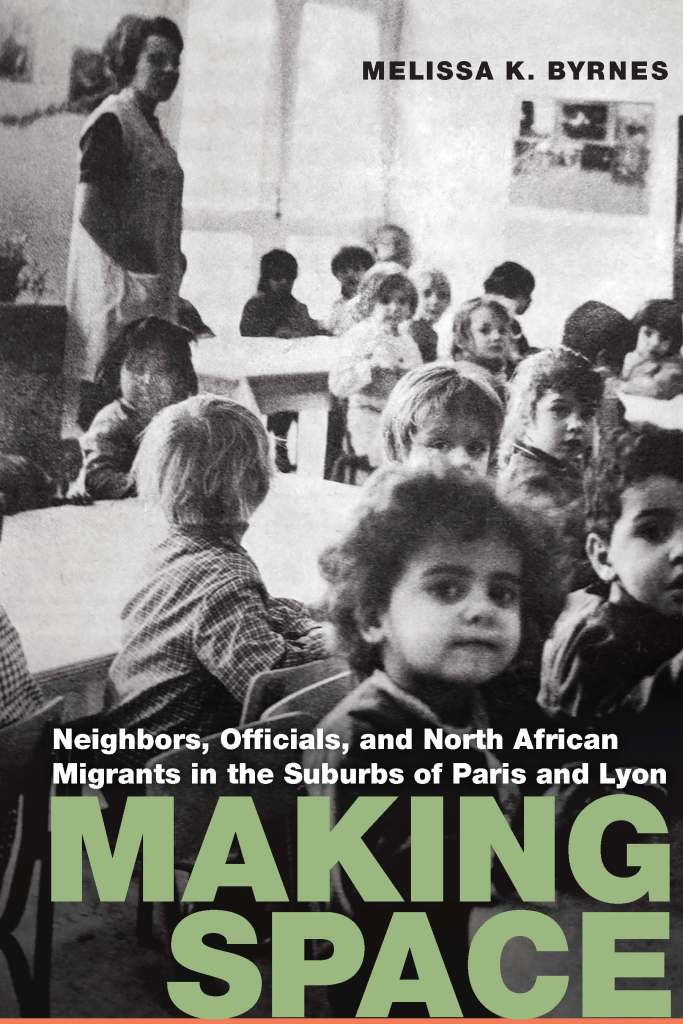

Melissa K. Byrnes is a professor of modern European and world history at Southwestern University in Georgetown, Texas. Her latest book, Making Space: Neighbors, Officials, and North African Migrants in the Suburbs of Paris and Lyon was published in January.

Since the 2005 urban protests in France, public debate has often centered on questions of how the country has managed its relationship with its North African citizens and residents. In Making Space Melissa K. Byrnes considers how four French suburbs near Paris and Lyon reacted to rapidly growing populations of North Africans, especially Algerians before, during, and after the Algerian War.

Introduction

A View from the Field

The first official goal scored at the Stade de France in Saint-Denis was kicked by a Frenchman of North African descent in January 1998. Zinedine Zidane is, of course, less known for this particular football match (a friendly game against Spain) than for captaining the French national team to a spectacular World Cup victory against Brazil in the same stadium later that year. Zidane was born in France—in the Castellane neighborhood of Marseille. His father had migrated from Algeria in 1953 and actually worked for a number of years in Saint-Denis, long before the stadium was built in that city. The 1998 FIFA trophy was widely hailed as a testament to France’s diversity, to its strengths as a multiracial republic, to its dedication to making Frenchmen out of migrants like Zidane’s father. Images of Zidane and his teammates were projected onto immense screens throughout France in a celebration of brown, Black, and white unity. French fans likewise projected a multitude of meanings onto these men’s bodies and accomplishments. Lilian Thuram—the other star footballer of the moment—was one of the first to worry that of all the potential messages to emerge from the victory, the story to gain traction was one of republican integration. Raising up the supposed success of the French system to mold its citizens recalled long-standing imperial doctrines that elevated white Frenchness over the myriad contributions and cultures of its global subjects. To claim the 1998 World Cup as a national victory, the actual voices, experiences, and accomplishments of its Black and brown participants were often occluded or ignored.

National glory is not, however, what interests me about this moment—nor is this book a national history. My fascination with this stadium and these victories is rooted in their location on Saint-Denis’s soil. The Stade was built in the Parisian banlieues (suburbs) as part of an urbanization plan closely overseen by Saint-Denis’s communist municipality. The “France” in the stadium’s name refers not to the country but rather to the geological plain around Paris. This slippage between the local and the national, between inhabited space and imagined identities, is central to the story I tell. Saint Denis, like its stadium, might be seen as a testament to inclusion: a workers’ city that embraced its migrant communities, embodying over many decades the euphoric belonging of the fabled “black-blanc-beur” (“Black-white-Arab”) World Cup win. Yet even the Stade’s experience of community interaction is more complex than those two games in 1998. Take, for example, the friendly match between the French and Algerian national teams in 2001, during which spectators hissed through the French anthem and later spilled onto the field, causing the game to be canceled. Or consider, more chillingly, the bombings that were part of the constellation of attacks in November 2015. Diversity may often be showcased in the Stade de France, but it is also critiqued, challenged, and even attacked. Examining Saint-Denis’s municipal activism on behalf of the city’s North African population over the decades after the Second World War offers a closer look at the stakes of supporting—and failing to support—local migrants. This local story gains still deeper meaning when compared with those of other suburban cities around Paris and Lyon.

Making Space: Neighbors, Officials, and North African Migrants in the Suburbs of Paris and Lyon examines the ways that predominantly white French administrators, actors, and activists got involved with their North African neighbors by detailing daily, on-the-ground experiences in four French suburbs: Saint-Denis and Asnières-sur-Seine in the Paris region and Vénissieux and Villeurbanne around Lyon. Chronologically, this research emphasizes the development of support for North African migrants from the inception of the Fourth Republic (in 1945), through the decolonization process, and up to the moment, in 1974, when the global economic crisis triggered a moratorium on migration to France. The historical willingness of autochthonous members of these local communities to engage with North African migrants proves that there are workable models of inclusive republican citizenship that do not require newcomers to negate all other personal identities—whether cultural or religious.

This book answers the question of why particular local actors in France advocated for North African migrant rights and welfare in the decades following the Second World War. It details the experiences of municipal officials, regional authorities, employers, and others to establish the wide variety of strategies that French community leaders developed in the face of rapidly growing North African (especially Algerian) populations. I pay close attention to how these actors explained and justified their positions regarding North African migrants, to the claims they made on broader social and political ideals, and to the connections they drew between their actions and their worldviews. I explore the ways that local attitudes and policies, whether inclusive or exclusionary, formed and re-formed communities. This view from below offers a deeper understanding of the decisions that led to the current tensions surrounding race, migration, identity, and belonging in French society.