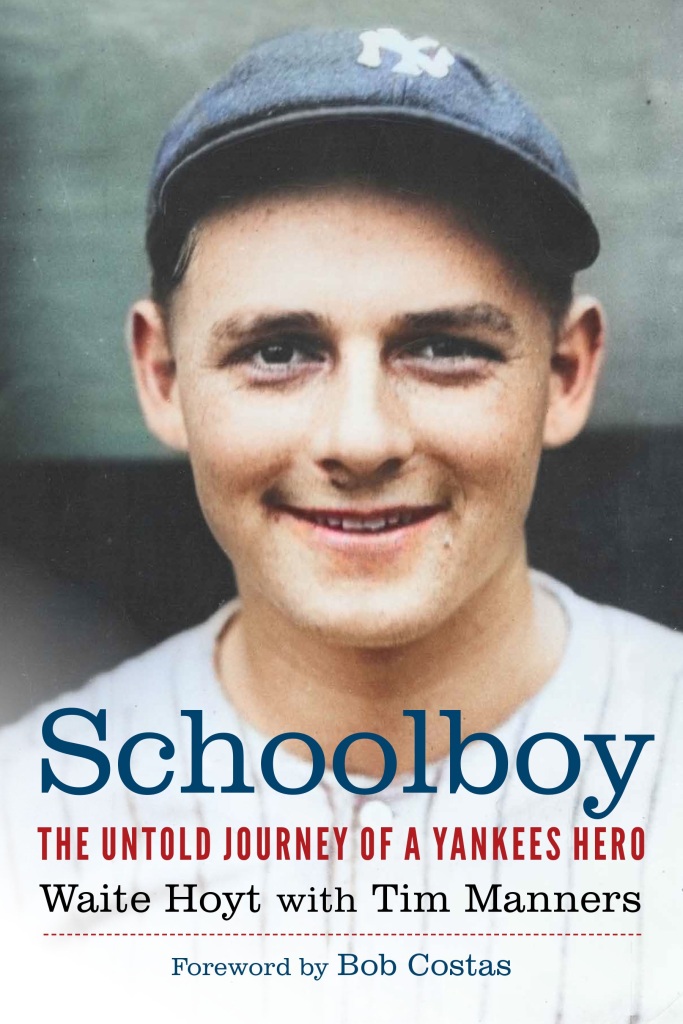

Tim Manners is a writer, communications consultant, and baseball fan. He is the coauthor of the memoir Schoolboy: The Untold Journey of a Yankees Hero (Nebraska, 2024). To learn more visit: https://schoolboyhoyt.com/ or follow the author on Facebook.

Waite Hoyt’s life was a puzzle. Picking up the pieces was pure joy.

Tim Manners

“Why didn’t your dad ever finish his memoir?”

It wasn’t the first time I had asked Christopher Waite Hoyt this question, but his response startled me.

About a year earlier, Chris had sent me a PDF of a smattering of book chapters by his late father, Waite Hoyt, who was a Hall of Fame pitcher for the legendary 1927 New York Yankees and beloved radio voice of the Cincinnati Reds. I was curious as to whether there was more.

Chris stared at his rigatoni for a moment and then looked me straight in the eye. “There are eight boxes of his papers,” he said. “I’m going to have them sent to you.”

I don’t have a picture of the boxes sitting on my front porch but I remember exactly how I felt. Excited, yes, but also worried. What if there was nothing of value in those boxes? What was I going to tell Chris? I dragged the boxes upstairs and cut them open, one at a time.

I went through them very slowly, the first time to get a sense of what was there and the second to begin carving out what I might be able to use. Most of the contents had been neatly organized into file folders, some bundled up in string, by Chris’s cousin, Ellen, who did the actual work of mailing the boxes to me. Ellen had the material because of her own painstaking efforts in the early 1980s to compose a biography of her uncle Waite.

Newspaper clippings. Letters. More newspaper clippings. More letters. Photographs. Unfinished memoir chapters written by mainly unidentified authors. Notes. Radio Scripts. Cassette tapes. Still more newspaper clips and letters. Waite Hoyt received a lot of press in his day. Most of the contents seemed interesting but not particularly relevant to a memoir until I happened upon a thick, plastic, three-ring binder of interview transcripts.

Paydirt.

Just a couple of years before his passing, Hoyt sat for a series of interviews with Ellen, which covered almost the entirety of his life. I thought I could use these transcripts as the backbone of a memoir, in his own words. It was a place to start. I felt I had something.

The first step was to re-type the transcript, editing along the way for clarity and setting aside parts that didn’t quite seem to fit. The process helped me internalize the material. Elsewhere in the boxes, I found a separate interview transcript in which Hoyt talked about what he wanted his book to be. He was quite outspoken about what he didn’t like about his previous memoir attempts. The gist of it was: They didn’t say what he wanted to say, the way he wanted to say it.

As Hoyt saw it, his book should be more than a collection of amusing, tell-all baseball anecdotes; it should capture his life as a man, and how he addressed internal conflicts with himself. He underscored that point in his notes over and over again. He was clear that the book should provide lessons learned so that future generations might benefit from an understanding of his mistakes. This intent to edify was almost too perfect for a guy nicknamed “Schoolboy,” which he earned at age fifteen, after New York Giants manager John McGraw signed him to play ball.

He also complained that his various memoir attempts didn’t sound like him. This became abundantly clear to me just by reading the raw interview transcripts and listening to recordings of radio interviews and his broadcasts. Hoyt had a plainspoken eloquence and enjoyed using a fancy word now and again. Some of his would-be ghostwriters affected almost a caricature of his true voice, trying a bit too hard to sound colorful and entertaining. He was those things but in an understated, relaxed, more conversational way. Once I had a handle on this, I could easily separate Hoyt’s writings from those of his various “literary doubles.”

The overarching challenge was figuring out what should go where. The timeline had to move forward chronologically but not to the point where it would become predictable. It was important to use flashback and flashforward at key inflection points to give the story the dynamics it deserved. It was like working a giant jigsaw puzzle. What belonged in the picture, what didn’t, and where?

One specific challenge was that Hoyt indicated he wanted his story to start with his dismissal from the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1938, which ended his big-league baseball career. It wasn’t until I found a scrap of paper, in his nearly indecipherable handwriting, that I was able to make this work. Fortunately, Chris’s wife Nancy has a real talent for reading inscrutable penmanship, yielding the first two paragraphs that start the book.

Another big problem was a gap in the narrative after 1938, covering Hoyt’s transition into radio and his simultaneous descent into alcoholism. Chris mentioned that his dad had donated some of his papers to the Cincinnati Historical Society, and – sure enough – they had some text covering his radio days. Hoyt also said he wanted to include a comparison between baseball in the 1920s and the 1960s, and the Society had that material, too.

Hoyt’s alcoholism story was relayed in almost excruciating detail in a recording of an epic speech he gave before Alcoholics Anonymous, which Chris gave me on cassette. This provided what was needed to explain Hoyt’s experience with addiction fully, particularly his advice to fellow travelers.

It seemed fitting to end the book with “Christopher’s Question,” given that this project began with my question to Chris: “Why didn’t your dad ever finish his memoir?” Chris’ question to his father was: “What could we possibly learn from you?” This provided a framework for Waite Hoyt to come full circle, reflect on his life’s lessons, and express his hope that others might learn from “Schoolboy.”