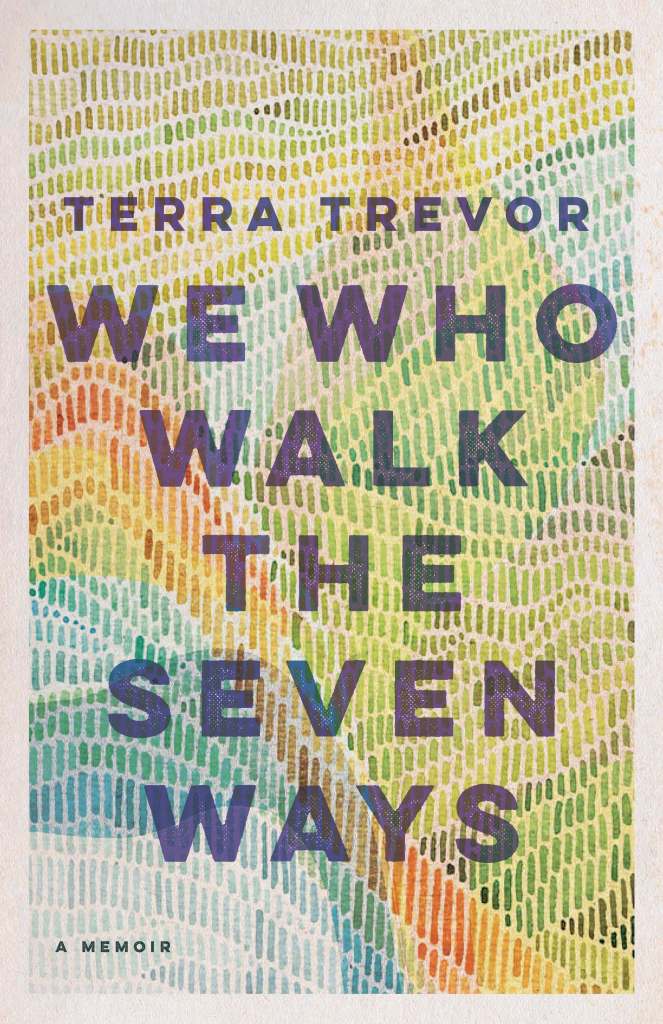

Terra Trevor is an essayist and memoirist who draws from her Native roots and the natural world. Her stories are steeped in themes of place and belonging. She is the author of two memoirs and is a contributor to fifteen books in Native Studies and Native Literature. Her new memoir We Who Walk the Seven Ways was published by the University of Nebraska Press.

We Who Walk the Seven Ways is Terra Trevor’s memoir about seeking healing and finding belonging. After she endured a difficult loss, a circle of Native women elders embraced and guided Trevor (Cherokee, Lenape, Seneca, and German) through the seven cycles of life in Indigenous ways. Over three decades, these women lifted her from grief, instructed her in living, and showed her how to age from youth into beauty.

With tender honesty, Trevor explores how the end is always a beginning. Her reflections on the deep power of women’s friendship, losing a child, reconciling complicated roots, and finding richness in every stage of life show that being an American Indian with a complex lineage is not about being part something, but about being part of something.

Growing Old in a Beautiful Way

This morning I watched a red-tailed hawk circle up from the bottom of the canyon and glide past, wings spread wide to catch the wind. Then a second hawk glided past, and then a third arrived in the air and was joined by a fourth and all of a sudden Auntie showed up, just as strong in my mind as she had been in life. I remembered the way she answered my questions by telling me to put it in my holy center and not to think about it too much, to just let the answer come in its own time. I returned to the times when Auntie would surprise me by talking about what was good medicine and bad, and how to figure out what to do, and not do, if power was given.

Her shoulders had bent as she grew older, but Auntie always stood straight as a young girl when she told me her stories. Her words sounded like wind shaking the leaves on a tree.

Auntie’s stories began in the evening, as the sun was going down. The turquoise beads she wore on Sundays made her white hair shine. Her skin was like dark smooth clay and when she laughed, she held her hand in front of her mouth hiding her bare gums. Before bed, she gathered me and all of the girl cousins and reminded us to remember our dreams and to feel our feet growing up from the ground so we would be able to find our paths within the great circle in relation to how Indigenous people viewed the world.

According to Auntie, there was woman’s work leading to our spiritual path. The stories she told spoke of the female cycles of life within the medicine world. But she never used those exact words. Instead, she told stories, the ones helping Native children to understand there was a natural world and a spirit world, and places connecting the two, through which some could, if they were supposed to, move from one to the other. Except I thought her stories were like fairy tales. There is a Grandmother Spider creation story, a traditional tale, and I thought she told it to me to keep my mind off all the teasing I got at school. The kids called me “spider,” because our last name was Webb, and I had long skinny legs.

Auntie and I grew up in a family where all of the women had known their great-grandmothers, and our great-grandmothers had known their great-grandmothers. From her great-grandmother, Auntie learned how to dig sweet root from the ground. Yellow root, lady’s slipper, she knew all of them. She knew about the helper plants. The ones that were not strong enough on their own and could help other medicine plants become stronger when combined.

“Time goes in a circle,” Auntie said. Everything that has ever happened, or ever will happen is going on all around me, always. I didn’t understand. Yet I could feel roots beneath my feet reaching back or forward into an invisible place where time lived. I thought of it as one big swirling windy place, where all of the things that would happen in the future, and what happened before I was born, came together and had a meeting of sorts. I didn’t know how, only that it did. Most of the time I couldn’t comprehend what Auntie was telling me and I tucked her words into my heart for safekeeping.

After Auntie passed into the spirit world, other Native women came into my life shaping me into the woman I am today.

I’ve been thinking about how lucky I am.

I’m thankful for Marie. She taught me how to age from youth into beauty. Marie had the radiant warmth and gravitational pull of a sun, and the ability to let you know there is no place in the world she would rather be than with you in the moment. She spent her early years living near Santo Domingo Pueblo and over a course of time became introduced to some of the tribes who maintained camping grounds on their reservations where well-behaved strangers were welcomed. Marie knew when to be quiet and she listened well. She had a favorite reservation she liked to camp on where there were hiking trails galore.

Galore, that was one of Marie’s words, and fiddlesticks. On days when a piece of writing was giving me a hard time, I went to Marie.

“Fiddlesticks,” she said. “Let yourself listen, and instead of trying to think something up, write about what you are thinking.”

Having already passed through the other cycles of womanhood, Marie was walking The Way of the Teacher. Much later I would begin to understand she was walking The Way of the Wise Woman, a Medicine Path. But Marie never used those words. Instead, she lived her life as an example. She was wise enough to offer the impression she was no different than any other old woman. This is what drew me in.

And there was Ann. She probably knew every Native woman in town, and I thank my lucky stars we became good friends. She was filled with stories, her own stories, and she retold traditional Native stories. The oral tradition, the teaching stories that guide us from the mundane to the spirit world. Her words flowed through the room, around the campfire, floating in the air, the impact of her words streaming down faces. I saw her voice.

Ann introduced me to the plants that make good basketry materials.

She held out a stalk of deer grass for me to examine.

“When immersed in water, baskets made with flowering culms become watertight as the stalk expands, making them perfect for water jugs and cooking baskets.”

Ann knew how to use wild plants for food, medicine, and crafts, and about the plants used to make natural dyes and which ones are gathered from below sea level or above timberline. She gave off no pretense as she walked The Way of the Ritualists. Like Marie, she is wise enough to offer the impression she is no different than any other older woman with a strong connection to the natural world.

While writing We Who Walk the Seven Ways, I had intimate chats, wandering back over time with Marie, Ann, Mary Lou, and Irene. Dancing with Irene long after the moon was full, wearing moccasins beaded in colors of sunrise, clouds, and blue skies, her buckskin dress swaying. Irene danced the powwow competitions, Women’s Buckskin style, Northern, in the Golden Age category. At seventy-five with her tight jeans, blue-black hair, and flirty personality, Irene reminded me so much of my Aunt Jo, that I had to keep reminding myself that she wasn’t my Aunt Josephine.

I loved the flow of these women in my life, the ones with the grandmother faces, walking the seven ways. How they made me laugh and told me the truth even when it was hard for me to listen.

While writing, I brought them all back and made them come alive again. The women who over three decades, lifted me from grief, instructed me in living, showed me how to age from youth into beauty, to grow right as an elder, and grow old in a beautiful way.