Elizabeth Shick is an award-winning novelist whose writing is influenced by her many years abroad, including six years in Myanmar. With a background in international development, she has also lived and worked in Angola, Gambia, Italy, Malawi, Mozambique, and Tanzania. Shick currently divides her time between Dhaka, Bangladesh, and West Tisbury, Massachusetts. She holds a master of fine arts from Lesley University and a master of international affairs from Columbia University. The Golden Land is her debut novel.

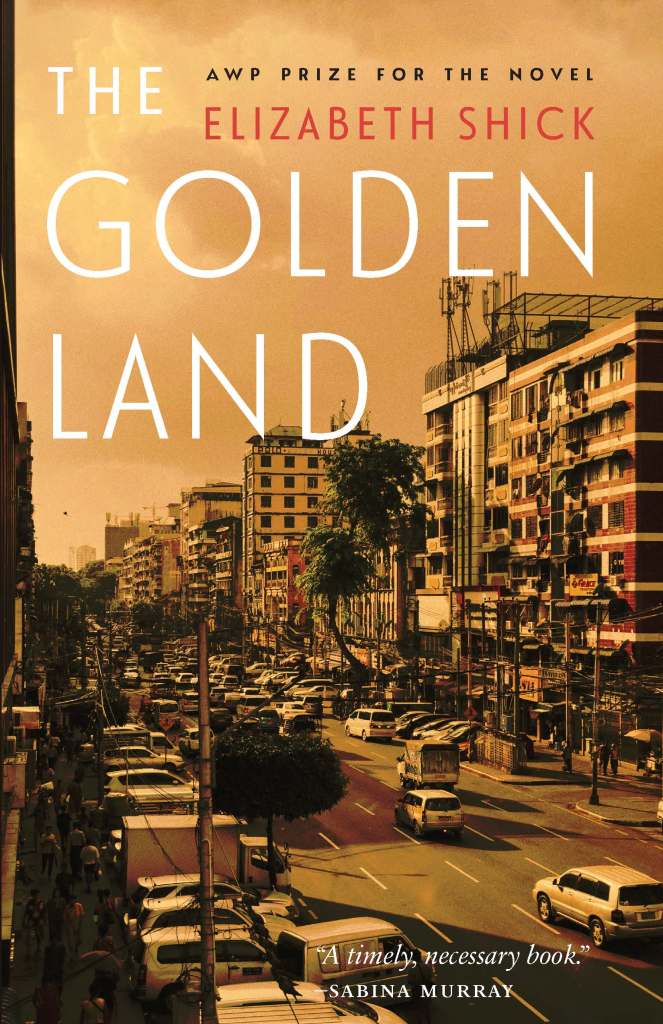

Winner of the AWP Prize for the Novel, The Golden Land digs deep into the complexities of family history and relationships. Etta Montgomery is a Boston-based labor lawyer coming to terms with the love and loss she experienced as a teenager during a 1988 family reunion in Burma. When Etta’s grandmother dies, she is compelled to travel back to Myanmar (Burma) to explore the complicated adolescent memories of her grandmother’s family and the violence she witnessed there. Full of rich detail and intricate relationships, The Golden Land seeks to uncover those personal narratives that might lie beneath the surface of historical accounts.

ONE

Boston, Massachusetts

2011

A thumb of ginger lies on the cutting board alongside several cloves of garlic and a pile of small, red shallots, as if any minute Ahpwa might resume chopping, grating, crushing. She was adamant about assembling her ingredients before beginning to cook, my grandmother.

Suddenly, I’m eight years old again, standing next to her with my eyes ablaze, enduring the fumes of the onion in exchange for a rare taste of intimacy. “Always prepare everything in advance, Myi, so the oil does not burn.” We looked alike back then, or rather, I looked like her. A quarter Burmese, I had my grandmother’s dark eyes and moon-shaped face, the same shiny, black hair, mine tied into an obedient braid down the center of my back, hers twisted into an elaborate knot, the impossibly long tresses coiled around a tortoiseshell haircomb at the nape of her neck before cascading, serpent-like, down the center of her back.

On closer inspection, the ginger is slightly shriveled, having sat in the open air for nearly a week now. I pick up the cutting board and tip the abandoned vegetables into the trash, then uncurl my fingers one by one and let the cutting board slide in on top of them with a thunk.

The kitchen looks much as it always did, the white jasmine hanging above the sink, an empty teacup in the drying rack. The only signs of distress are the open cupboard above the stove and an overturned chair. As I set the chair upright, a can rolls out from under the lip of the kitchen counter. I bend down to pick it up. Chaokoh 100% premium coconut milk, imported. The top of the can is crushed on one side, its label furrowed. So that’s what Ahpwa’d been after when she fell.

Staring down at the mangled can in my hand, I feel a dull ache in my chest. Not sorrow, something else. A sense of wrongness, that this is not how her life was meant to end, that our family might have turned out differently. When I was little—before the family reunion in Burma, before I met Shwe and attended the protest march, before Ahpwa’s breakdown and my parent’s divorce and Ahpwa’s declaration that we were no longer Burmese, before all that—she only ever cooked with home-pressed coconut milk obtained by grating the thick, white kernel of a mature coconut then squeezing the grated meat through a fine cloth. To think she died reaching for the canned stuff, imported from Thailand no less.

My younger sister, Parker, is the one who found her. Since quitting, or perhaps losing, the latest in a long string of jobs, Parker’d begun to spend quite a bit of time here, eating most of her meals with Ahpwa, sometimes even spending the night. Our parents died years ago, so for a while now it’s just been the three of us on this side of the world. Now two. Monday evening, Parker arrived at Ahpwa’s to find her sprawled out on the kitchen floor.

As I entered the ER, Parker began to weep. “Etta,” she cried, heaving the full weight of her body upon mine as if she were nine, rather than 29.

I stumbled backward, the glare of disinfectant and antiseptic lights making my head swirl. I couldn’t believe Ahpwa was gone.

These last few days have been a blur of undertakers, morgue technicians and well-meaning acquaintances. Parker attends to the well-wishers. She’s better with people than I am, warmer and more accessible. At least, that’s what she says, and she’s probably right. As the lawyer in our little family of two, I attend to the paperwork, which suits me fine. I find the banality of the forms soothing.

Parker hasn’t wanted to return to the house, so I’m taking care of all the logistics here, too. Next up are the estate lawyers and real estate agents, today’s visit the first step toward putting Ahpwa’s house on the market, which begins with cleaning out perishables. I open the fridge: three bundles of spring onions, a posy of cilantro, one packet of thin egg noodles, and one whole chicken sitting unwrapped on a plate, its little feet tucked under its bum, skin dark and rubbery from prolonged exposure to the cold air. Ohn no khauk swe, that’s what Ahpwa’d been preparing the day she died, noodles in a coconut chicken soup. My childhood favorite.

~

Discovering that I’m taking a rare day off work, Parker asks to meet for lunch. After the usual tussle over venue, we agree on a café not far from where we grew up. I arrive five minutes early to find her seated in a booth near the window. In the center of the table, next to the salt and pepper, sits the black and red urn I’d planned to collect from the funeral parlor later today.

“I’m taking Ahpwa back to Myanmar,” Parker announces as I slide into the booth.

I unpeel my eyes from the gold-engraved urn and stare at my little sister. Seven years younger, Parker enjoyed a freer relationship with our grandmother than I did. But I can’t believe this is what Ahpwa would’ve wanted. And what does Parker know of Burma? She’d been only six when our family visited in 1988, too young to know about the protest march, or what I’d witnessed before we so hastily left.

“Why?” I ask.

“It’s what she wanted, her dying wish.” A lock of wavy, blond hair has come loose from her ponytail, framing the right side of her freckled face with the illusion of innocence.

“I thought she was unconscious when you found her.”

“Well, yeah.” She places her hand at the base of the urn. “But she talked about Myanmar all the time.”

“She actually said she wanted to be buried there? Rather than here, beside her own daughter?”

Parker flinches at the mention of Mother and I feel bad. Our mother had never been particularly attentive, surrendering our care to Ahpwa as she worked long hours to keep up with mortgage payments, but her death—ovarian cancer—had been hard on Parker, just 16 at the time. I was also sad, but too busy with law school to let myself wallow for long. With our father having succumbed to a heart attack years earlier, Mother’s passing left Ahpwa as Parker’s official guardian, and me feeling perpetually guilty for not being a more patient and understanding big sister.

“My point is that this was her home for the last sixty years,” I continue, gesturing beyond the window to the formation of birch trees sheltering the sidewalk, the familiar T station across the street. “Surely she’d want to be here. With us.”

The waiter approaches, scans our faces, and veers toward another table.

“Sorry, Etta, but when was the last time you talked to Ahpwa? I mean really sat down and talked with her about something not on your to-do list?”

Her words sting. For years, I’ve avoided spending any meaningful time with Ahpwa, still so resentful about everything— Burma, my parents’ divorce, being forced to leave Shwe. But what irks me now is the insinuation that Parker understood her better than I did.

Parker takes a slow breath, her fingers cradling the base of the urn as if seeking strength from within. “I think she felt guilty about leaving her brother, you know? And some other guy, too. Some long-lost love.”

I resist the urge to roll my eyes at this latter point, the idea of Ahpwa having a long-lost love almost as absurd as her wanting to go back to Burma. But then Parker’s always been a romantic. Despite what she may think, I admire this quality in her. I wish I still believed in that kind of sweeping, predestined love. But to paint Ahpwa as a romantic, too? Uncompromising, intense Ahpwa? I don’t buy it. Unless. Unless Ahpwa really had changed, and I’d failed to notice.

“Fine. But can we talk about this rationally? I mean, the ashes will keep––”

“I leave Tuesday.”

A shaft of sunlight hits our table, exposing tiny particles of dust drifting between us. I want to grab the urn away from her. Run out of the restaurant and far away. But there’s something menacing about Parker’s hand resting there, as if she’s waiting to swat mine away.

“Tuesday?”

She looks at me for several seconds, weighing her words, I suppose. “Look, I’m sorry…I just didn’t want you to talk me out of it, ok?” Her blue eyes are so steady, so full of conviction, I almost don’t recognize her. Growing up, Parker flitted from one pursuit to the next, leaving sticker books open on the kitchen table, abandoning Barbie dolls mid costume-change, and later, swapping boyfriends like shoes. Only a year ago, I was helping her fill out job applications, lending her money when she hit a rough patch. But something’s changed.

“What about your visa?” Neither of us have Burmese passports, Ahpwa having given up her citizenship when she moved to the U.S. in 1945.

“It came in the mail yesterday.”

That Parker’s managed to navigate the bureaucracy of the Burmese Embassy on her own astounds me.

“Vaccinations?” I ask.

“Had my last one this morning. Typhoid.” She cups her hand over her upper arm as if seeking sympathy, or admiration. But I’m too stunned to respond, the depth of her concealment upending my longheld belief that she needs or wants my help.

“And no, I’m not asking for money. I got my student loans deferred. So, I can manage.”

Her reasoning is maddeningly short-sighted as usual, but at least she’s thinking about money—in her own, Parker kind of way. And though neither of us can bear to say it out loud, there will be money from the sale of Ahpwa’s house, though perhaps not as much as Parker expects. As I meet her gaze, I realize she’s waiting for my blessing. That’s what this is.

“Are you sure it’s safe?” I ask.

“Yeah.” Her eyes soften. “It’s not like before, Etta. There’s a civilian government now. And Aung San Suu Kyi’s been released from house arrest. Myanmar’s changing.”

I know all this. I must’ve read every Globe article about Burma in the last 10 years. They say the country’s opening up. But I don’t trust it—the memory of what I saw as a teenager, the terror I felt, more compelling than any reporter’s analysis. Because once you’ve witnessed tyranny, you can never un-see it, never quite believe it won’t lash out again. This is what Parker doesn’t get. Why would she?

“You could come with me, you know.”

“Are you crazy? There’s no way I can get a visa before Tuesday. You know that.”

“The week after, then.”

I want to believe she’s sincere, that she wants me by her side on this journey. But all I feel is manipulated, Parker pulling my strings like one of Ahpwa’s old marionettes.

“I have work.”

“Come on. It’ll be fun. We can meet up with Shwe. Don’t you ever wonder about him?”

My chest tightens at the mention of our second cousin. A memory of him being pulled away by his mother. Of myself, writing letter after letter without hearing back. There’ve been times in my life when all I wanted was to return to Burma, to see him again and figure out what happened, why everything fell apart. Visiting Burma had been too risky back then, the military having tightened its hold over the country, and now…now, I like my life the way it is. After all those years of law school and kiss-ass entry-level positions, my career as a labor lawyer is finally starting to gel, even if I am on the employer side of the courtroom.

And then there’s Jason—sweet, steady Jason. After nearly a decade living together, we’ve decided to marry next year. He started to ask me once before, when I hadn’t been ready, and the pain from my equivocation almost broke us. I worry that following Parker on a half-baked quest to Burma will re-open that wound.

“It would mean a lot to Ahpwa,” she says.

“Not fair, Parker. You want to go, then go. I have enough regrets of my own. Last thing I need is you piling more crap on top.”

“Fine.” She hesitates for a moment. “I just thought it might be good for you to get away. To get some perspective on…you know, everything.”

My irritation flares into rage. She’s referring to Jason, of course. She never did approve of him, thinks he’s boring, controlling.

“Some of us have commitments, Parker. We can’t just fly off to the other side of the globe at a moment’s notice.”

She looks away, and my fury fizzles back to uncertainty. The truth is, part of me is curious about the new Myanmar, about my cousins and aunties and uncles, about Shwe. But another part is terrified, both by the risk of renewed violence—it was only a few years ago that unarmed protestors were being gunned down in the street—and by the possibility of peace unearthing long-buried secrets, concealed by the military regime. But I can’t stop Parker just because I’m afraid.

After lunch, we walk out to the sun-dappled sidewalk, Parker holding the ashes out in front of her like a Buddhist monk proffering his alms bowl.

“You need a ride to the airport?”

She shakes her head.

“Let me know when you get there.” Worry catches in my throat. “And be careful, okay?”

Parker shifts Ahpwa’s ashes onto her hip, and we embrace clumsily, the lip of the urn stabbing my ribs. As I watch her walk away, I wonder about her offer, whether she intended all along to invite me, or if the idea came just now—a genuine, spontaneous desire to include me in her quest. I wish we were the kind of sisters who didn’t hide things from each other, who told each other when they felt joy and when they felt pain. This isn’t Parker’s fault.

~

Jason and I sit on our new sofa, sipping coffee and reading our respective papers—his, the online version of the Times, mine, the paper version of the Globe. He’s wearing jeans and a flannel shirt, laptop balanced on his thighs, argyled heels on the coffee table, a look of concentration on his boyish face. He prefers his hair trimmed short, but today it sneaks over the temples of his glasses, longish, the way I like it. Sitting together like this on a Sunday morning is one of my favorite rituals, but right now, all I can think about is the fact that Parker left for Myanmar five days ago, and I haven’t told him.

Jason doesn’t like talking about emotional stuff, but he will when necessary. His mother raised him well in that respect, taking pains to ensure he wasn’t governed by avoidance like the other men in her family. At least that’s what she told me the first time we met, as we sat alone in their sunny, Pennsylvania kitchen, a pot of homemade chicken stock simmering on the stove. She wanted me to know what a catch her son was, what a good man I’d happened upon. I’ve been thinking about this exchange recently because of how solicitous he’s been about Ahpwa, urging me to take more time off work, asking if I want to talk. I don’t.

All this is to say that I’ve had ample opportunity to tell him about Parker’s trip, ample time to disclose both my admiration—that she’s saved money, is showing initiative, and doing something she believes in; and my concerns—that she’s impulsive, irresponsible, and in a country prone to eruptions of state-sanctioned violence. Yet I’ve said nothing. The clumsy truth is that Parker going to Myanmar has me thinking about Shwe, about everything we went through together, and the terrible way it ended. I wonder what he’s doing now, if he’d want to see me again. Why he never wrote. And these aren’t thoughts I want to share with my fiancé. I know every detail of Jason’s childhood, from the name of his pet rabbit to the first girl he ever kissed, but I never told him what happened on that trip to Burma, and I never told him about Shwe.

“What’s up with Parker?” says Jason, looking at his watch. “Shouldn’t she be pestering you about now?” She typically calls Sunday mornings, a habit going back to childhood when we spent the day with our father.

“She went to Myanmar,” I say from behind my mug of coffee.

“Really? When?”

“Tuesday.”

Our eyes meet, and I wonder if he’s going to say something about my not telling him.

Instead, he says, “And lumped you with all the estate crap? Unbelievable. I hope you didn’t lend her money again.” His gaze returns to his laptop.

This is how we speak about my sister. I complain how irresponsible or needy or flighty she behaves, and he backs me up, pointing out how fortunate she is to have me to clean up her messes. I don’t know how to tell him that this time is different, that she hasn’t asked for my help, that I’m not the one in control.

“She took Ahpwa’s ashes.”

His hazel eyes flick up from the screen to search mine. Jason got along well with Ahpwa—she was always on her best behavior with him—but he knows how conflicted our relationship was. I’ve told him about her impossible standards and endless hours of tutoring, at least, if not about the haircut and smashed dishes.

“God, Etta. You must be furious. She’s your grandmother, too.”

It’s nice that he’s always on my side, but right now his words make me feel more isolated and alone.

“I don’t know. I think maybe she needed to go there for personal reasons.” I want to say more, but each detail withheld over the years seems to lead to another, creating a tangle of half-truths and omissions that I can’t explain my way out of in one sitting.

“How long’s she gonna to stay?”

“A week, maybe ten days?” Parker didn’t give a return date, but this is what I’ve been telling myself. Two days to get there, three to deal with the ashes, and two to get back.

“Did she go that time, when you were growing up?”

“Yeah, we all went: Mother, Father, Parker, Ahpwa.” I don’t mention that this was the last family trip we ever took, nor does he seem to catch the significance of my parents being there together— they divorced within the year, Father’s heart surrendering not long after.

“But she was only six.” I stand up to put my mug in the dishwasher. “I doubt she remembers much.”

“You didn’t want to go with?” He types something on his laptop.

I stare down at his profile, day-old stubble lending a rugged, more masculine quality to his soft features. He doesn’t know that I’m staying here for us.

“It’s not that simple,” I say.

“Sure it is. Look.” He turns his laptop so I can see the display.

Suddenly there it all is, all the beautiful, terrifying images in my head reduced to a series of thumbnail photos: the magnificent Shwedagon Pagoda glittering in gold; steel-helmeted riot police marching in procession; smiling women and children, their faces smeared with thanaka; bloodied demonstrators lying on the ground; and the implausibly serene Aung San Suu Kyi, her trademark flower tucked firmly in her hair.

Only Shwe is missing.

I sit back down, the empty mug slippery and cold between my hands. I’ve seen all these images before, but never like this, good and bad side by side. How is it possible for such beauty to exist alongside such evil? This is what confounds me. Jason doesn’t get it. I can see as much from the eagerness in his eyes. Like Parker, he thinks it’s easy: hop on a plane and scatter some ashes. I stare at the screen, searching for something to say that won’t worry Jason any more than he already is.