Leslie Patten has worked as a horticulturist, habitat specialist, and landscape designer. After moving to Wyoming, she has volunteered at the Buffalo Bill Museum of the West—preparing bird and mammal specimens and measuring wolf skulls for scientific research. Patten is the author of several books, including Shadow Landscape: Notes from the Field; The Wild Excellence: Notes from Untamed America; and Koda and the Wolves. Her most recent book Ghostwalker: Tracking a Mountain Lion’s Soul through Science and Story, Expanded Edition (Nebraska, 2024) was published in October.

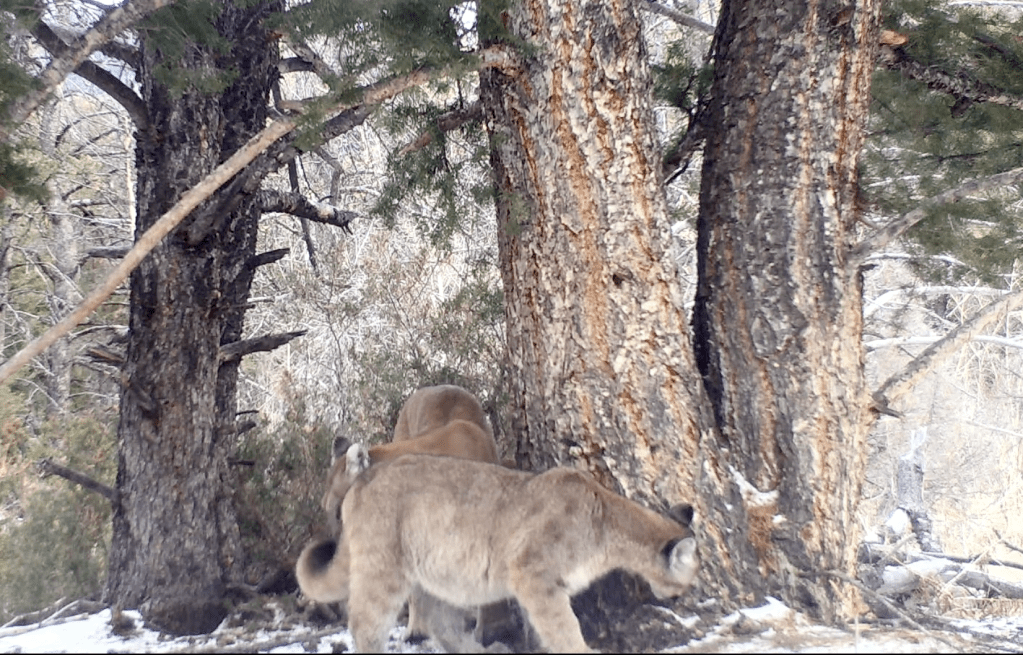

It was early April, and we just had heavy snow in Wyoming. I hiked to my camera sets, part of my ongoing study of mountain lions in the area, and unloaded photos of a nine-month-old kitten. What was troubling was that just a few months earlier, in December, I’d captured video of that kitten with his sister and mom, looking healthy, exploring scents, and playing. But now he looked gaunt and ragged. Today there were no captures of his sister or his mom. He was alone, wandering from one camera set to another. The photos were troubling because mountain lion kittens don’t disperse from their mothers until between fifteen and twenty-four months. Mountain lion mothers will stash their kittens in one spot while they hunt, but something was obviously wrong here.

I was very familiar with the mother of this particular kitten. She had only one good eye. Her blind eye appeared bluish in the daytime and had no eyeshine at night. I’d been following her since she arrived at my study area as a young disperser four years earlier. As a young cat with only one good eye, I felt I could safely assume this was a genetic defect. In that early first video, One-Eye was caterwauling, a shrill howling indicating she was looking for a mate. But she had no luck because it wasn’t until March a year later, in 2021, that I saw her again, this time looking quite pregnant. She successfully raised two kittens to disperse and then was pregnant again in April 2023.

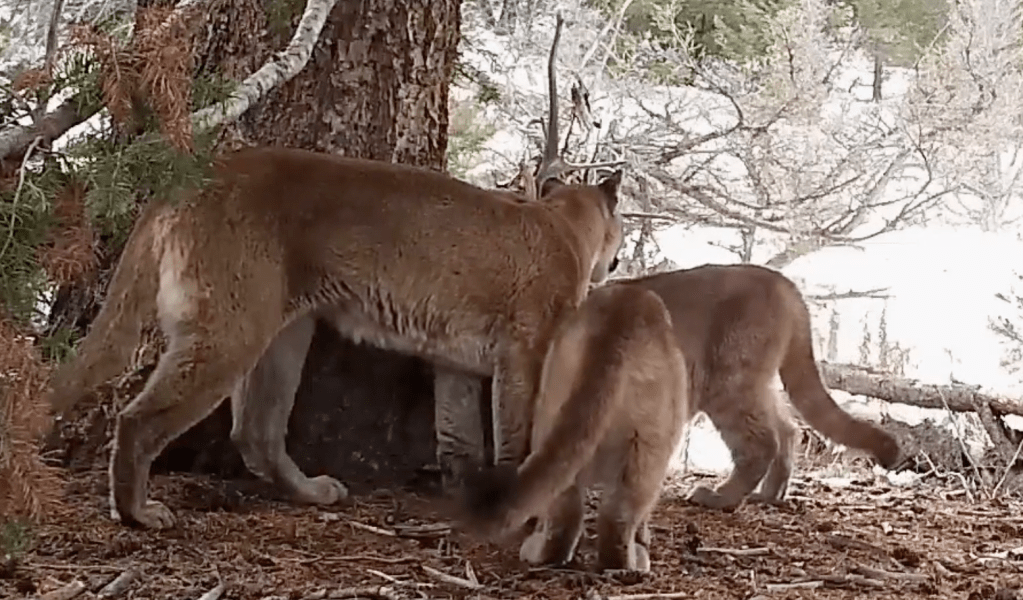

Our deer herd is migratory, meaning around early May they head into the high country of Yellowstone National Park. Once a mountain lion’s kittens are able to travel, around two to three months, they will accompany their mother on her forays. The kittens learn the seasonal routines and their mother’s territory. Sometime in late October, our deer herds begin to trickle back to lower elevations. It wasn’t until December 4, 2023, that I saw One-Eye’s kittens from this second litter for the first time. Now about seven months old, they were growing fast, spending time chasing each other and nuzzling mom.

Mountain lions with kittens need to kill a deer about every four or five days, although they are opportunistic and can feed their family with multiple small kills. A lion biologist in Yellowstone National Park, tracking a female with four kittens via a GPS collar, told me the mother was almost exclusively killing marmots for twenty days. My one-eyed mother was not only a successful hunter and provider for her family, but also a protector, guarding her kittens from wolves and many other dangers. Having only one working eye would surely limit her vision. To me, One-Eye was inspirational—a symbol of love and caring, courage and grit.

Kittens younger than fourteen or fifteen months without a mother probably won’t make it on their own. In a video captured by Mountain Lion expert Mark Elbroch’s Jackson, WY study, a mom brings a wounded deer to her two one-year-old kittens. You can see the kittens perplexed. “How do we kill this deer so we can eat it?” they appear to be thinking. Although the deer was still alive, it was too wounded to move much. The kittens took several minutes until finally one of them dealt the mortal bite to the neck.

I knew this lone kitten wouldn’t survive. I also had the distinct feeling that mom and the smaller kitten were already dead; this male was a trooper, trying to survive on his own with his limited skills and knowledge. At nine months, his survival education was far from complete.

I reached out to Dan Thompson, the large carnivore specialist for Wyoming Game and Fish, who completed his PhD on mountain lions in the Black Hills, to check if a hunter had brought One-Eye in. I knew he was deeply passionate about mountain lions from my interviews with him for Ghostwalker, and if I got an answer, at least then I’d know what happened. Mountain lions don’t have distinctive markings telling them apart, but a cat with only one good eye could be easily distinguished. Hunters are required to bring their kills to the local Game and Fish office to be sexed and aged. Wyoming law states that mountain lions traveling with kittens cannot be harvested. Research in Wyoming shows that during the winter months, mothers are away from their cubs about 50 percent of the time, and they could be away longer if their cubs are under six months old. It wouldn’t be a surprise if One-Eye had stashed her kittens and, while hunting alone, a houndsman had mistaken her for a solo female.

Usual protocol dictates that Game and Fish would not inform me how many female lions were killed in my area, a small sub-section of a much larger hunt zone. Yet Dan checked in with Luke Ellsbury, our local regional biologist, who also inquired of resident houndsmen. I suppose the photos and stories of this unique cat touched many at the department. The response was that there was only one female harvested in my area during the entire hunt, and she was not One-Eye.

I spent much of April and May looking for any remains of the three cats. I know my study area well, but a lion’s territory is vast, with a female lion’s being anywhere from fifty to one hundred square miles. My study area was barely seven square miles. I tried to think like a lion. If I were injured or starving, where would I go? A wounded or dying cat might crawl into a small, protected space, invisible to me. I relied on my dog, Hintza, to smell out their scent but he came up empty.

That May I had a chance to speak directly with Ellsbury. I showed him photos of the lone kitten. He concurred the kitten was in bad shape. But he also gave me new information. Two mountain lions had been reported dead in my area, probably discovered by houndsmen’s dogs. Ellsbury analyzed the scene and found that both these lions were killed by wolves. Wolves in Yellowstone and the surrounding forests are heavily GPS collared, so it wasn’t difficult for Ellsbury to determine that these lions were killed by Yellowstone’s Shrimp Lake wolf pack. The pack had been traveling back and forth outside Yellowstone Park’s boundaries. We have our own local wolf packs. These wolves were interlopers, looking to expand their territory while following our winter elk herd. Yet not all dead cats are reported or even discovered.

My guess is that One-Eye was either killed by wolves or in a fatal accident. With sight in only one eye, she may have been more susceptible to wolves and other hazards, especially while hunting. Her smallest kitten probably succumbed to starvation early on, while the more adventurous male tried to make it on his own, at least for a few weeks to a month.

This was the end of a memorable four years in my study area. An identifiable cat was gone. I mourned the loss of One-Eye. She taught me a lot about the tenacity, adaptability, and spirit of these wild animals. I did take some comfort knowing she met her demise via threats in her known world, however harsh, rather than from a hunter’s bullet. Yet I believe her life and death provide lessons for us regarding the day-to-day risks cougars live with, their low density on the landscape, and the impact we humans overlay on their existence. These include hunting, but also habitat loss and roads. I miss the thrill of catching her on my camera, but I’ll never forget observing such a magnificent animal push through obstacles to successfully care for her kittens.

2 thoughts on “From the Desk of Leslie Patten: Searching for ‘One-Eye’”