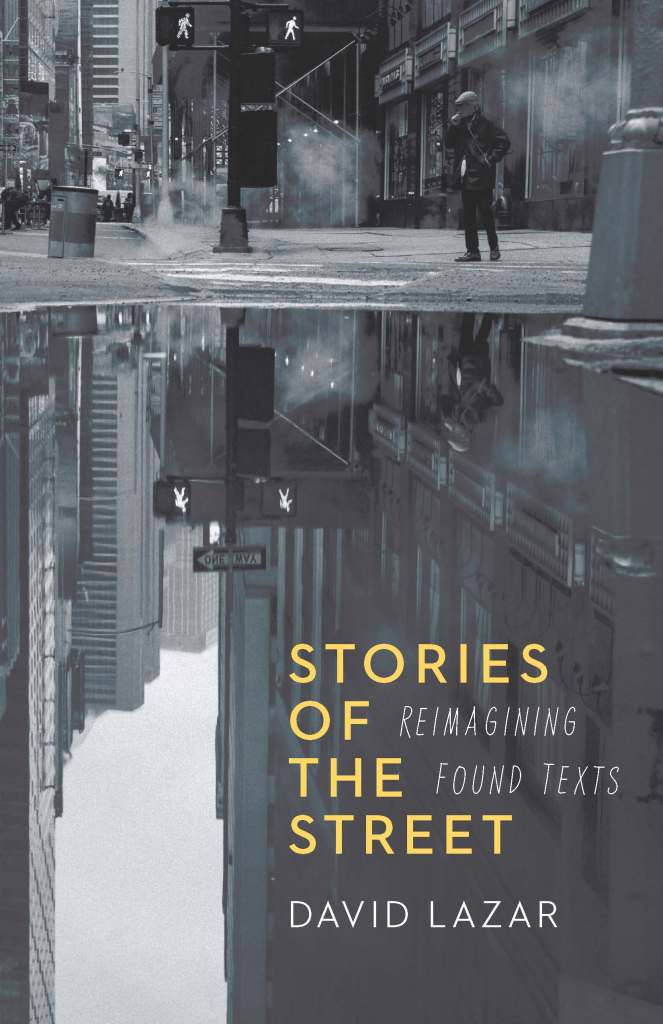

David Lazar is the author or editor of numerous books, including Celeste Holm Syndrome (Nebraska, 2020); I’ll Be Your Mirror: Essays and Aphorisms (Nebraska, 2017); Truth in Nonfiction; Occasional Desire: Essays (Nebraska, 2013); and The Body of Brooklyn. His most recent book Stories of the Street: Reimagining Found Texts (Nebraska, 2024) was published in November.

When walking down the street, it is not uncommon to see lost items that have escaped their proper receptacles, but how often does one stop to read the messages left behind? David Lazar has stopped often, capturing the pieces of a “lost world on the streets” and thinking about the life of the discarder from the fragments left behind.

Stories of the Street is a series of imaginative meditations—through prose poems, short-short essays, microfictions, and prose pieces without precise genre distinction—of what it means to encounter lost or discarded texts.

To the Reader

For the last ten years or so, I’ve noticed that there are texts everywhere; the ground is full of messages. Some are written by hand, some printed; there are scraps of paper and schoolbooks, advertisements and quickly scribbled telephone numbers, lists and equations, postcards and abstruse lines on lined or unlined pages, untranslatable. At some point I became fascinated with the world of ephemeral messages at my feet and began stopping to read and then photograph them in place, not sure at all what, if anything I might do with them, or what they might mean, but sure of my fascination, of my sense that there was this sub-world, this arcane lost world on the streets, of messages that had escaped their bottles, their owners or carriers, perhaps dropping listlessly from pockets like open mouths, crumbs on the ground I might follow. They were lying listlessly along with the leaves, in the gutters as the rain started, or the fading like dissipation of time spent walking aimlessly on the street, threatening their very existence with illegibility, or partially readable, like a textual dementia that challenges you to make sense of what is lost.

This book is in thrall to Walter Benjamin: the lyrical synecdoche of the city; the city as casual historical oracle. Fragments of what George Orwell calls “scraps of useless information” that might be revelatory given time.

Once again, via Benjamin: the city is a two-way street. In “One-Way Street” Benjamin writes,

What is “solved?” Do not all the questions of our lives, as we live, remain behind us like foliage obstructing our view? To uproot this foliage, even to thin it out, does not occur to us. We stride on, leave it behind, and from a distance it is indeed open to view, but indistinct, shadowy, and all the more enigmatically entangled. Commentary and translation stand in the same relation to the text as style and mimesis to nature: the same phenomenon considered from different aspects. On the tree of the sacred text both are only the eternally rustling leaves; on that of the profane, the seasonally falling fruits. (Reflections: Essays, Aphorisms, Autobiographical Writing [New York : Schocken Books, 1978], 67–68)

The “foliage” I found isn’t meant to be solved. Nor do I wish to turn the indistinct into an enigma. Instead, what Benjamin calls “commentary and translation” are my way of confronting, imaginatively, and one can only hope sympathetically, these fallen fruits and giving them a much more profane than sacred second life, and “ambiguity replaces authenticity” (Reflections, 75).

I’ve noted the approximate date and place where some of these texts were found, not because they especially shed light on the contents themselves but as a kind of footnote, a nod to the hybrid nature of what I’ve written, the plainest denotation of which might be called “responses,” a charming generic abyss that prose occupies when formal affiliations are oppressive, inappropriate, or just unavailable. Some might call these responses hybrids, a term of some marginal use that has already become somewhat mossy. I’d probably prefer circus acts, maybe just because it sounds so recherché. No animals, however, have been either involved or ill-used.

I have written some responses to images, as well as texts; they are alternate texts. Those of you who wander cities understand the lure of the stray image, the absurd, ironic, surreal, uncanny tableau that appears on the street of crocodiles. I have included a few of these as interludes, entr’actes between the messages lacking bottles that have caught my eye as I walked and walked, sullenly, moodily, occasionally however with a strangely jaunty amusement, down streets near and far, in cities—I’ve never met one that wasn’t interesting.

Gazing at surfaces, the flaneur may as well call his project, “On the Virtues of Looking Down.”

Or: the world is a bottle with no message inside. We write the messages ourselves and once in a blue moon the sea concedes.