Sonja Trom Eayrs is a farmer’s daughter, rural advocate, and attorney. She is involved in several rural advocacy organizations, including the Socially Responsible Agriculture Project, Farm Action, Land Stewardship Project, and Dodge County Concerned Citizens. Trom Eayrs also serves as the business manager for the Trom family farm in Dodge County, Minnesota. For more information about the author, visit sonjatromeayrs.com. Her latest book Dodge County, Incorporated: Big Ag and the Undoing of Rural America (Bison Books, 2024) was published in November.

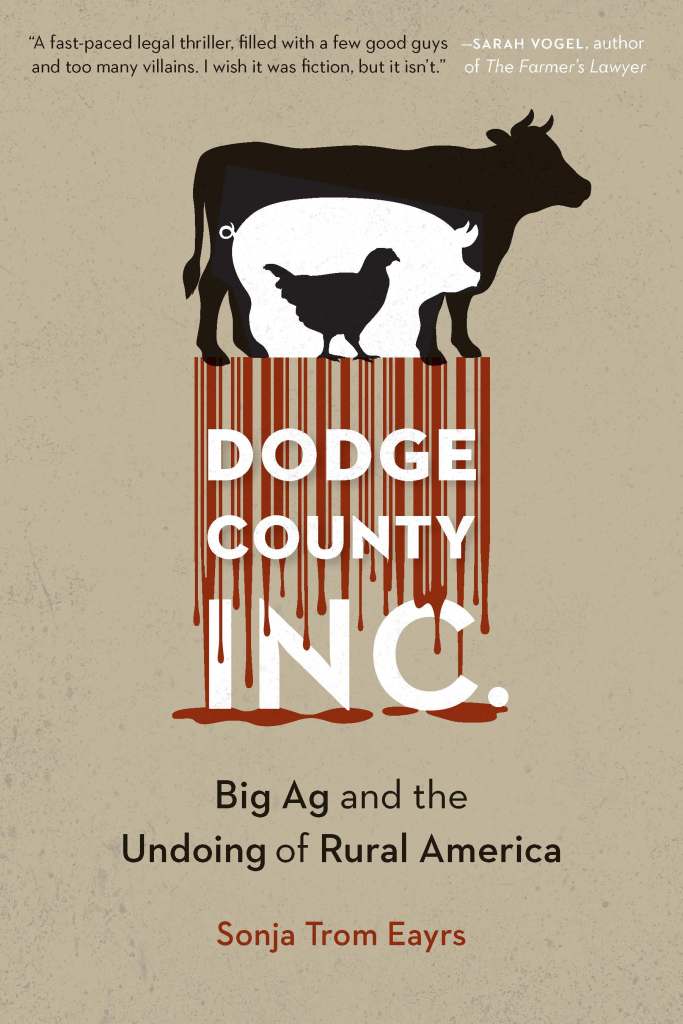

In a compelling firsthand account of one family’s efforts to stand against corporate takeover, Dodge County, Incorporated tells a story of corporate malfeasance. Starting with the late 1800s, when her Norwegian great-grandfather immigrated to Dodge County, Trom Eayrs tracks the changes to farming over the years that ultimately gave rise to the disembodied corporate control of today’s food system. Trom Eayrs argues that far from being an essential or inextricable part of American life, corporatism can and should be fought and curbed, not only for the sake of land, labor, and water but for democracy itself.

Introduction

A Readiness for Responsibility

My father, Lowell, died in 2019 after living a long, full life. He appears often in this book; in a way, he was my motivation and my muse. During Lowell’s lifetime, particularly in his twilight years, he witnessed dramatic changes in Dodge County, Minnesota, where his grandfather settled in 1892 upon emigrating from Norway. A palpable emptiness had overtaken farm country, marked by the absence of grazing animals that once peppered the landscape, the consolidation of local schools as the population declined and town centers eroded, and the shuttering of small-town businesses. The county and township roads were crumbling, laden with potholes and frost boils thanks to the large semis carrying hogs, manure, and feed between the nearby factory farms and the corporate delivery points.

In my youth, families put us children on bus number 2, which wound its way through the countryside and dropped us off in our hometown of Blooming Prairie on the southwestern edge of Dodge County. During a conversation with my father several years before his death, he described the specter of a new driver operating school buses in Dodge. It was a corporate driver, and the name of our transformed home was painted in bold, black lettering against the school-bus yellow: Dodge County, Incorporated. The corporate driver was not afraid to leave farm families and rural neighbors behind as it drove its empty bus. The children of farmers no longer stood waiting at the ends of long driveways. The main street in Blooming Prairie was lined with empty stores, and a sea of gray hair filled area church pews on Sunday mornings. A generation of farmers was ominously absent—and we knew the source of this sorrow.

Dodge County, Incorporated tells the story of industrial-scale factory farming: the pollution, the waste, the metamorphosis of the thriving, verdant countryside into bleak commercial zones. It is the story of my hometown, echoing with the story playing out in rural farm communities across the United States—one that is fueling a cultural and political shift in rural America. This is also the story of my family. We watched as our 760-acre farm was encroached upon in all directions by the look, feel, and overwhelming stench of “Big Agriculture.” We witnessed firsthand the effects of Big Ag that are rarely discussed in mainstream food and farm media: the hollowing-out of rural communities, the steady unraveling of the fabric that once stitched neighborhoods together, and the erosion of democratic values in service to the corporate bottom line.

What big box stores have famously done to shutter Main Streets across the United States, Big Ag has been doing, with the same ruthless efficiency, to rural farm communities such as ours. My family’s fight to preserve our farm, and our community’s reaction to it, laid bare the growing societal tensions and even violence shaped by the rural populism that has been on display across the nation. We were ostracized, harassed, and subjected to false police reports, threatening phone calls, and garbage dumped in the roadside ditches bordering our farm—all for asserting our right to live free of the air and water pollution that comes from cramming thirty thousand hogs cheek by jowl within a three-mile radius of our home.

For me, this journey of heartache and sadness has turned to hope and determination to fight for Big Ag reform. When I left Dodge County decades ago to forge my path as a mother and attorney, I never would have guessed that my frequent visits home would lead to where I am today.

In the fall of 1977, my parents put me on a plane bound for New York City with my bright red electric typewriter in tow. I was a farm girl through and through, having spent my childhood weekends and afternoons sitting on the fender of my father’s John Deere 4020. During fall harvest, I had darted straight to the fields after school, enjoying many peaceful hours on the combine as we combined soybeans or picked corn. Now I was hundreds of miles away, at Vassar College in Poughkeepsie, New York. I suffered terribly from homesickness during my freshman year.

The Hudson River Valley was admittedly beautiful. I relished the history tucked into every corner and visiting the lavish mansions of the Roosevelts and the Vanderbilts. It was an aesthetic, dignified backdrop as I ran around with new friends and danced with handsome men in uniform at the nearby U.S. Military Academy at West Point. But none of it compared with the beauty of waving grain. I longed for fall harvest. During my sophomore year, I transferred to Carleton College and the familiar, pastoral setting of Northfield, Minnesota. There, I graduated with a degree in political science and an appreciation for the democratic process.

I returned to the family farm often. I still loved working the fields. Though I had wanted to attend law school for many years, I postponed that dream as my husband, Douglas, and I did things backward and had our children first. In the fall of 1986, now a mother to two young daughters, I entered law school. After I graduated from Marquette University Law School in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, we moved to the Twin Cities metro area, where I work as a family law attorney. Our family returned to southern Minnesota almost every weekend so our daughters could see their two sets of grandparents. Like me, Douglas was raised on a family farm in Dodge County.

During those drives home, we realized rural America was changing. The changes were slow at first; then they happened fast—very fast—as multinational corporations such as Hormel Foods, JBS Foods, Tyson Foods, and Smithfield Foods asserted control over rural areas, including Dodge County, during the late nineties and the aughts. Small, independent livestock farmers left farming altogether or signed Big Ag contracts, allured by terms that supposedly offered financial stability but ensnared many of them in debt. This period, as well as those contracts, are explored in chapter 3, “The Big Pig Pyramid”; chapter 4, “The Meeting at Lansing Corners”; and chapter 5, “Get Big or Get Out.”

We observed the transforming landscape. Fences disappeared. Cows, hogs, and other animals no longer grazed in the fields. I recall saying to my husband, as I looked out the window with a creeping feeling of bewildered sadness, “Where are the animals?”

That was the beginning of a long journey. My family became involved in local efforts to halt the advance of factory farms and the air pollution, water contamination, and emerging cancer clusters that came with them. As I recount in chapter 6 (“The Battle in Ripley Township”), members of my family were involved in two citizen’s efforts: one, to prevent the installation of a large gestation sow facility near the Swiss community of Berne in northern Dodge; the other, to challenge the installation of Ripley Dairy, which would have been the largest dairy operation in the state of Minnesota at the time.

Douglas and I watched these battles—one successful, the other not—from somewhat of a distance, and our feeling of responsibility grew.

Then, in 2014, a young farmer sought a permit for yet another factory farm, this one right next door to my parents’ farm. This industrialized swine feedlot would have no family living on it—no farmhouse with people who cared for the land, only corporate interests hoping to squeeze every dollar out of the 2,400 hogs that would stand, every day, stuffed into a crude, dark building. The proposed project would produce manure equivalent to a town of nearly seven thousand people and spew hydrogen sulfide, methane, ammonia, and other dangerous gases into the air encircling my parents’ home.

That is when I jumped in with both feet. My mother, Evelyn, had just entered the local nursing home, and my father, at eighty-five years old, was tasked with becoming her caretaker while continuing to farm the land. In chapter 9, “Getting to Know Your Neighbors,” I begin the story of how my family banded together to prevent the county’s approval of the permit for that factory farm. When our initial efforts failed, my parents filed a lawsuit against Dodge County officials and local swine operators. Chapters 10, “Industry Watchdogs”; 13, “The Corporate Bully”; and 14, “In the Trenches,” recount the harassment and intimidation that frontline families such as ours face in our own communities when we become involved in the national movements to fight back against the excesses of Big Ag.

The book’s final chapters tell the larger story of Big Ag’s negative impacts on rural communities across the country and of the hyper-local citizens’ efforts that have arisen to protect communities from the environmental and health consequences. Though sparsely covered in the national press, disagreements over agricultural issues in rural communities deeply impact our national politics, coloring everything from agricultural policy to antitrust legal scholarship to the trajectory of environmental policies and regulations.

I was first driven to write Dodge County, Incorporated after experiencing how my family was—and continues to be—treated in the years following our initial lawsuit. But as the book unfolded, I homed in on something bigger—namely, the corporate model itself. It perverts people’s best impulses and amplifies our worst, as local economies are highjacked and as communities increasingly serve not themselves but the interests of multinational conglomerates, many of them based overseas.

For me, the questions raised by factory farming aren’t only about the economy, the environment, and the well-being of rural residents—though these issues are certainly important—but also about the nature of community. Are we, as people, beholden to one another? And if not, to whom, or what, are we beholden?

In these pages, I hope to show that despite what the industry wants us to believe, most farm communities are not united in their acceptance of the corporate-driven farming model. We don’t need to organize our economy, our communities, and our agricultural practices around the profiteering of Hormel, Cargill, Smithfield, Tyson, and other multi-national giants. We must instead reclaim and celebrate what many generations of farmers embraced: nurturing the land and the animals, maintaining a sustainable food supply, promoting public health, valuing clean air and the opportunity to swim and fish in healthy local streams and lakes, and cherishing nearby neighbors and friends. In failing to align with these values, large corporate interests continue to create conflicts in rural areas, conflicts that then reverberate in America’s cities and towns.

The German theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer once wrote, “Action springs not from thought, but from a readiness for responsibility.” We must wrestle the steering wheel back from the hands of the corporate driver. In rural America today, we must support the steady, growing resistance of people who are committed, not to restoring an imperfect past that led to our current predicament, but to building a future in which we are no longer dependent on the corporate trough.