David Yee is an assistant professor of history at Metropolitan State University of Denver. His latest book Informal Metropolis: Life on the Edge of Mexico City, 1940–1976 (Nebraska, 2024) was published in November as part of the Confluencias series.

In the 1940s, as Mexican families trekked north to the United States in search of a better life, tens of millions also left their towns and villages for Mexico’s major cities. In Mexico City migrant families excluded from new housing programs began to settle on a dried-out lake bed near the airport, eventually transforming its dusty plains into an informal city of more than one million people.

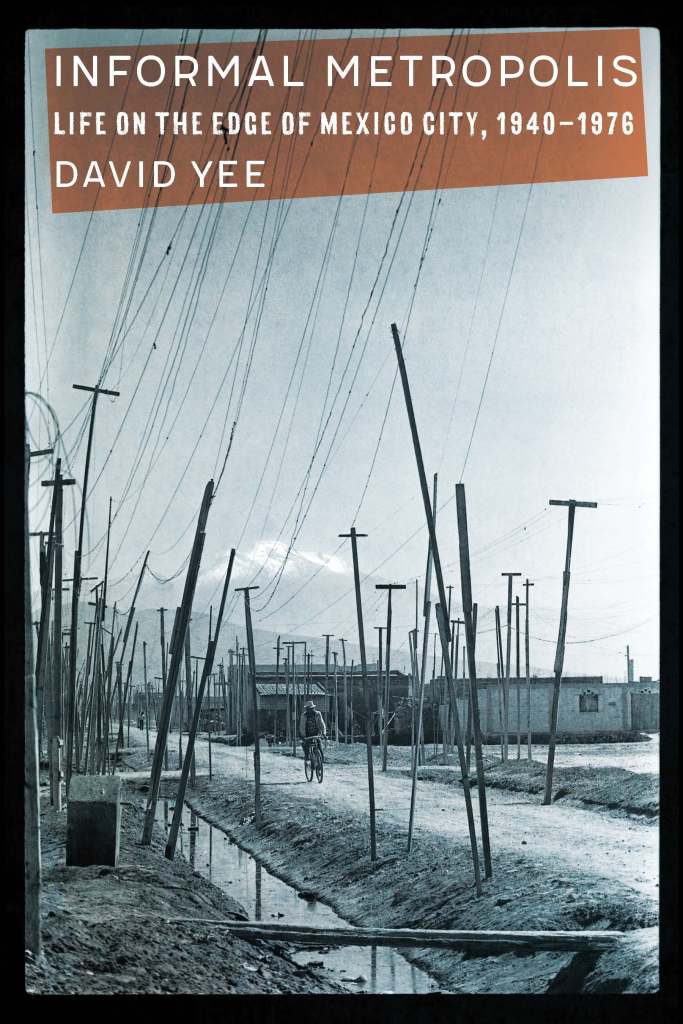

In Informal Metropolis David Yee uncovers how this former lake bed grew into the world’s largest shantytown—Ciudad Nezahualcóyotl—and rethinks the relationship between urban space and inequality in twentieth-century Mexico. By chronicling the residents’ struggles to build their own homes and gain land rights in the face of extreme adversity, Yee presents a hidden history of land fraud, political corruption, and legal impunity underlying the rise of Mexico City’s informal settlements.

Introduction

For over a thousand years, rustic settlements dotted the edges of Lake Texcoco. The majestic body of water was once part of five contiguous lakes nestled in the Basin of Mexico’s volcanic mountain range. Over time, various kingdoms and empires laid claim to Texcoco as generations of villagers continued to hunt and fish around the edges of the lake. However, after a succession of regimes drained most of its water, the villagers found themselves on the edges of Mexico City. By the middle of the twentieth century, with the former lake bed’s land tenure still in question, the newly surfaced land became a violently contested site. This conflict would inevitably shape the area as it grew from a cluster of crudely built shacks into an informal city of over one million people.

Rogelio Vargas Soriano was one of the millions of people who moved out to the former lake beds encircling the capital’s eastern periphery. Originally from the Mixteca region of Oaxaca, he moved to Mexico City in 1954 as a teenager. Prior to his arrival, he had spent several days on a bus traveling across the mountain ranges that lie between Oaxaca and the capital. Rogelio arrived in the San Lázaro Terminal with a few pesos in his pocket, the little his family could scrape together after a poor harvest season. He struggled to survive in the city’s growing informal economy yet had saved up enough money to purchase a plot of land in a new municipality called Ciudad Nezahualcóyotl (Neza). On the day he met with the land developer, he asked where his property ended. The developer threw a rock into a nearby marsh and told him it ended where the rock hit the water. Despite the lack of formalities, Rogelio signed the contracts, much like thousands of other poor migrants lured to Ciudad Nezahualcóyotl by the prospects of becoming a homeowner.

Raúl Ruiz Bautista arrived in the same terminal nearly ten years prior to Rogelio Vargas. Raúl Ruiz walked for days through the Mixteca’s mountainous terrain until he found a train station that connected him to Oaxaca’s capital. From there, he continued his journey to Mexico City in 1942. Unlike Rogelio, Raúl Ruiz maintained close ties with his fellow Mixtecs in Mexico City, organized a mutual-aid association to send funds back to the Mixteca, and worked closely with the National Indigenous Institute. Eventually, he found an office job with the Mexican Institute of Social Security, a position that gave him access to an apartment in one of the new housing projects built by the federal government in the 1950s. Located in the middle-class neighborhood of Narvarte, Raúl Ruiz held meetings in Spanish and Mixtec with other migrants from his village in a modern apartment equipped with services and a shopping center on the ground floor.

The parallel journeys of Rogelio Vargas and Raúl Ruiz Bautista reflect a common story shared by millions of Mexicans who left behind their small towns and villages for a new life in Mexico City. The commonalities shared by Rogelio and Raúl are striking, yet at some point their paths diverged and their lives moved in different directions. Why did one poor migrant from the Mixteca region gain access to a modern apartment with an elevator and hot water, while the other built his own home out of recycled materials near a polluted lake? Was the division between Rogelio and Raúl the product of their own decisions, or were there larger forces at play? These initial questions eventually led me to the central theme of this book: the relationship between urban housing and social inequality in mid-twentieth-century Mexico.

Rogelio Vargas’s and Raúl Ruiz Bautista’s stories are representative of a larger divergence that took place in Mexican society during the middle of the twentieth century. Over the span of two decades, from 1940 to 1960, inequality steadily rose, after which point, the country’s levels of inequality precipitously declined until the 1980s. Specifically, inequality peaked around 1963 and sunk to its lowest point in 1983. As one economist in the 1970s observed, “The Mexican miracle appears to have resulted in a redistribution of income in favor of its urban middle-class at the expense of the country’s top and bottom sectors.” Since then, historians have primarily focused on the nation’s “bottom sectors” to highlight Mexico’s comparatively high levels of inequality. In many ways, the current study of Mexico’s largest shantytown enriches this literature. However, to limit the scope of inquiry to Mexico City’s poorest shanty dwellers would overlook a distinctive feature of midcentury Mexico: the persistence of endemic poverty amid prosperity and upward social mobility. This reconfiguration was fully expressed in the crisis surrounding urban housing. As millions of rural migrants settled in Mexico City, housing functioned as a mechanism for upward mobility among the city’s incipient middle class at the expense of the informal poor.

Mexico City’s expansion was shaped by two kinds of mass housing. The first was the multifamiliar, a broad term associated with public housing complexes built for civil servants and middle-class families. Monumental in scale and modernist in style, the multifamiliar provided a national aesthetic for social welfare in midcentury Mexico. The second was the self-built home, a rudimentary shelter constructed by poor families at a distance from the state. As laborers in the informal economy, their precarious positions limited their access to financial credit, social welfare, and citizens’ rights. In this period, the multifamiliar and the shantytown were defined by each other, representing two possible futures for the Mexican metropolis. If the multifamiliar symbolized progress, rationality, and the quixotic optimism of high modernity, the shantytown reflected the failures of Mexico’s accelerated modernization. Nowhere was this duality more vividly expressed than in the Vaso de Texcoco.

The swampy remains of Texcoco’s lake bed became a proving ground for mass housing in Mexico City. It was here where Mexico’s largest shantytown, Ciudad Nezahualcóyotl, grew alongside Mexico’s largest government housing complex, San Juan de Aragón. I analyze these two contrasting areas to explore the relationship between geographic space and social inequality. In doing so, I argue that a person’s position in the formal or informal economy was the most decisive factor in determining where they lived in the metropolis. Beyond state institutions and laws, the inherent biases embedded in Mexico’s housing policies were also upheld and defended by the nation’s largest labor unions. In particular, the Confederation of Mexican Workers waged several struggles against the government’s attempts to provide a more inclusive program for informal laborers. Struggles surrounding housing helped solidify a broader reconfiguration of social stratification in midcentury Mexico.

Informal Metropolis traces the urbanization of the Vaso de Texcoco (Ciudad Neza and San Juan de Aragón) between 1946 and 1976. These years marked a period when the nation’s traditionally rural population declined in the wake of mass migrations to urban centers. During this period, in the press and the public imagination, Ciudad Neza represented a deformed, incomplete transition from “the rural” to “the urban.” By its sheer size and scale, Ciudad Neza gained particular notoriety as a city of extremes. In the 1970s, it was the site of the largest garbage dump and the largest shantytown in Latin America. It was also home to the largest protest strike for urban land rights and, subsequently, the largest land regularization reform carried out under President Luis Echeverría (1970–76). However, despite the extreme material deprivation evident in Ciudad Neza’s early history, a close study of its local archives reveals that the extreme nature of Ciudad Neza’s deprivation was more a product of policy than poverty. Though undoubtedly impoverished, Ciudad Neza’s extreme features can be traced back to the government’s unspoken practice of granting impunity to private developers who embezzled public funds designated for critical infrastructure projects.

Ciudad Neza’s historical record challenges many of the myths and common assumptions held about lawless squatters in Third World cities. In fact, most of Ciudad Neza’s residents were not squatters—broadly defined as one who settles on property without title or payment of rent—but instead were aspiring homeowners indebted to land developers. Documents held in Ciudad Neza’s municipal archives detail the fortunes reaped by private developers who fraudulently sold property lots with nonexistent services to unsuspecting families taken in by the prospects of owning land close to the city.

Nevertheless, a historian’s attempt to demystify past stigmas cannot negate the power they once possessed. Though fundamentally symbolic and ephemeral, social stigmas can exert a strong influence on the material conditions of a locale. Whether the Northeast of Brazil or the Southside of Chicago, the stigmatization of a region or area can influence policy decisions, financial investments, policing methods, and levels of corruption.