Scott D. Seligman is a writer and historian. He is the national award-winning author of numerous books, including The Great Kosher Meat War of 1902 (Potomac Books, 2020) and Murder in Manchuria (Potomac Books, 2023). His latest book The Chief Rabbi’s Funeral: The Untold Story of America’s Largest Antisemitic Riot was published in December by Potomac Books.

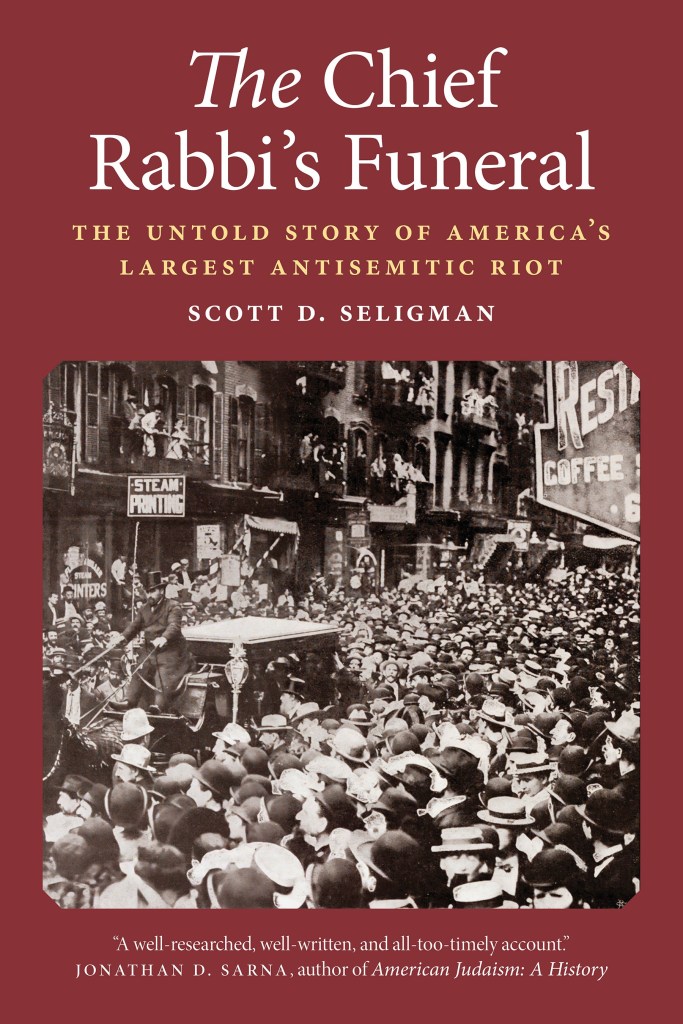

On July 30, 1902, tens of thousands of mourners lined the streets of New York’s Lower East Side to bid farewell to the city’s chief rabbi, the eminent Talmudist Jacob Joseph. All went well until the procession crossed Sheriff Street, where the six-story R. Hoe and Company printing press factory towered over the intersection. Without warning, scraps of steel, iron bolts, and scalding water rained down and injured hundreds of mourners, courtesy of antisemitic factory workers. The police compounded the attack when they arrived on the scene; under orders from the inspector in charge, who made no effort to distinguish aggressors from victims, officers began beating up Jews, injuring dozens.

To the Yiddish-language daily Forverts (Forward), the bloody attack on Jews was not unlike those that many Russian Jews remembered bitterly from the old country. But this was America, not Russia, and the Jewish community wasn’t going to stand for such treatment. Fed up with being persecuted, New York’s Jews, whose numbers and political influence had been growing, set a pattern for the future by deftly pursuing justice for the victims. They forced trials and disciplinary hearings, accelerated retirements and transfers within the corrupt police department, and engineered the resignation of the police commissioner. Scott D. Seligman’s The Chief Rabbi’s Funeral is the first book-length account of this event and its aftermath.

Preface

As I write this in 2024, the New York–based Anti-Defamation League (ADL) has just published its annual Audit of Antisemitic Incidents. This year’s edition testifies to the fact that 2023 marked America’s high-water mark for antisemitic assaults, harassment, and vandalism. In no year since 1979, when the ADL began counting, has the number of such incidents come anywhere near the 8,873 that occurred in 2023. Turbocharged by a surge in anti-Israel and anti-Jewish feeling associated with the Israel-Hamas war, it exceeded the tally of the three previous years combined.

The 161 violent assaults in 2023—a 45 percent increase over the previous year—involved a total of 196 victims. Had the ADL been around and been counting, however, they would have exceeded that number on just one day in 1902. On July 30 of that year, when the Orthodox Jews of New York’s Lower East Side buried their first and only chief rabbi, America experienced the single largest violent antisemitic incident in its history in terms of sheer numbers attacked and injured.

The most appalling aspect of the events of that day was not even the vicious assault on the huge crowd of Jewish mourners by blue-collar workers from a local printing press factory. That was dreadful and unprecedented in its scale, to be sure, but employees of that plant had a long history of harassing Jewish passersby. What was far more shocking was that the police themselves compounded the attack when they arrived on the scene. “They are the ones who should have arrested the aggressors,” the outraged Yiddish-language daily Forverts (Forward) protested. “Instead, they were the ones who perpetrated violence against the peaceful Jews a hundred times over.”

The assault on Chief Rabbi Jacob Joseph’s funeral procession was not the first such rite to be defiled by Jew haters in America. For that, one would have to go back at least to 1743, when the funeral cortege of Abraham Isaacs of Shearith Israel, the country’s oldest Jewish congregation, was assaulted by a mob. As the New York Weekly Journal reported at the time, his corpse was “insulted . . . in such a vile manner that to mention all would shock a human ear.” Isaacs’s body was finally interred, but only after someone apparently attempted to subject it to a posthumous conversion to Christianity.

As that example suggests, antisemitism in America is older than the United States itself, though violent attacks on Jews, at least those of any significant scale, are primarily twentieth-and twenty-first-century phenomena. This is the story of the first major one. The first one that garnered national attention. The one that ushered in a century that would, from time to time, witness more vicious attacks on America’s Jews.

But it was also the one that served notice on the country that Jews were now present in sufficient numbers, and had acquired sufficient political power, to fight back. Newly a part of the New York political establishment, Jews no longer had to accept mistreatment passively or with resignation. Through their hastily established East Side Vigilance League, they would wield their newfound influence to defend their interests and push for justice.

Decades before the spate of antisemitic violence that reared its ugly head during the civil rights struggles of the 1950s through the 1970s; before New York’s Crown Heights riot in 1991; and before the mass shooting at Pittsburgh’s Tree of Life–Or Simcha Synagogue in 2018, which was the deadliest as of this writing and in which one of my own elementary school classmates perished, there was the brutal attack on the chief rabbi’s funeral cortege. Its sole saving grace was that unlike several of the others, no one was killed in it.

FBI director Christopher Wray told the ADL in late 2022 that antisemitism motivated fully 63 percent of religious hate crimes in the United States, a number that has likely risen in the wake of the Israel-Hamas war. Such offenses target an ethnic group that makes up just 2.4 percent of the population. Unlike the 1902 riot, however, the modern variety of violent attacks on Jews, at least until the outbreak of the war, has usually been a premeditated strike by a lone hater. The various “crimes” these contemporary offenders attribute to Jews include support for civil rights or leftist causes, the State of Israel’s policies toward Palestinians, and alleged Jewish schemes to “replace” the white supremacists who peddle that particular baseless conspiracy theory.

Antisemitism remains alive and well among some in law enforcement. But although nearly all American Jews today—a poll by the advocacy group J Street put the number at 97 percent—report being concerned about Jew hatred, they do not generally expect to be at the receiving end of tear gas, tasers, or bullets from the police, at least not because they are Jewish. Not so Blacks and Hispanics. In that sense, the police role in the 1902 Grand Street riot has more in common with modern police brutality against people of color than against Jewish people.

In America today, it is unfortunately not at all difficult to envision police as agents of persecution instead of protectors and defenders. The 2020 video of Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin snuffing the life out of a helpless George Floyd with a knee on his neck has been seared into the public consciousness. It has catapulted the issue of police brutality toward minorities, especially Blacks, into the national conversation, where it has always belonged but seldom lodged for long. In several cities, echoes of the 1902 police actions reverberated in large-scale police assaults against those who protested Floyd’s killing.

Few photos of the events of July 30, 1902, on New York’s Lower East Side survive, and there were no videos, nor was there social media, to inflame public passions. But, as in the murder of George Floyd, coverage of the riot nonetheless brought violent ethnic hatred front and center, for at least a short time, and forced average people to see it for what it was. The good news is that in both 1902 and 2020, it was roundly condemned—by the newspapers, by politicians, by civic and religious leaders, and by the general public.

This book tells three related stories: the saga of New York City’s first and only chief rabbi; how his funeral gave rise to the single largest violent antisemitic incident in American history; and how, in its wake, the Jewish community organized and deftly deployed its newfound political clout to pursue justice for the victims and set a pattern for the future.

The events of 1902, although now well over a century in the past, unfortunately still resonate and continue to be relevant in our own times as we grapple with the purveyors of racism, antisemitism, anti-Muslim and anti-Asian prejudice, homophobia, and transgender phobia who act out their hatreds across the length and breadth of the land.

In 1902, New York’s Jewish community found that by uniting, organizing, and building alliances, it could hold the government accountable for taking to task those who did it harm. In the more than a century since then, organizations like the ADL, the American Jewish Committee, and the American Jewish Congress, all of which were established in the wake of the 1902 riot, have done more or less the same after incidents like the murder of eleven worshippers at Pittsburgh’s Tree of Life Synagogue. As they seek to leverage their political influence to combat discrimination and secure justice in modern times, they have, in effect, borrowed a page from the East Side Vigilance League’s playbook.

When people speak of antisemitism, or even of racism in general, it is often accompanied by a wringing of hands. People say it has always been with us and predict that it always will be. Eradicating it is a Sisyphean task, but we must never cease trying. At the very least, we can impose a significant and deterrent cost on it when it rears its hideous head in violent expression.

In 1902 the New York Jewish community showed us how.