Edward Armston-Sheret is a Fellow at the Institute of Historical Research, School of Advanced Studies, University of London. His new book On the Backs of Others: Rethinking the History of British Geographical Exploration (Nebraska, 2024) was published in December.

I recently sat down to talk with Professor Michael Robinson about my book on Time to Eat the Dogs, a podcast about science, history, and exploration. On the Backs of Others focuses on contributions and experiences of the various people and animals that made explorers’ journeys possible, but who rarely get the recognition they deserve.

During the interview, Michael asked me about an issue that has remained on my mind ever since: how different was the Anglo-Irish explorer Ernest Shackleton, from his contemporaries? This question fascinates me, as the degree to which Antarctica explorers were different from those that operated in other contexts is at the heart of my book.

Shackleton is an interesting figure within the history of labour and exploration. Most expeditions were profoundly hierarchical undertakings, and this was reflected in the way logistical work (such as cooking, cleaning, and carrying was distributed). In contrast, Shackleton, while never accepting challenges to his leadership, insisted that officers and scientists mucked in with such activities. One of my favourite images from the history of exploration shows the scientists of Shackleton’s Imperial Transantarctic Expedition scrubbing the floor of their living quarters. It is perhaps this attitude that means Shackleton remains a popular figure, even as there have been growing questions about the commemoration of other colonial-era explorers.

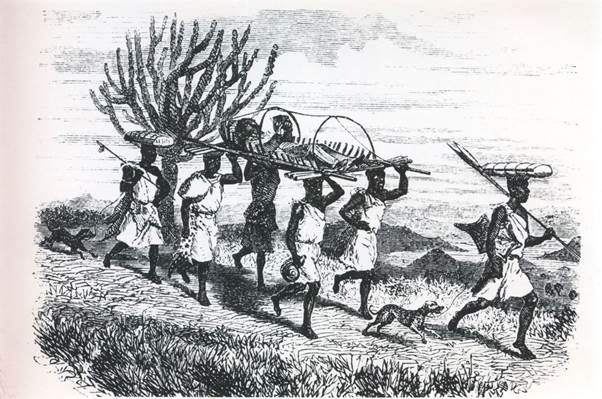

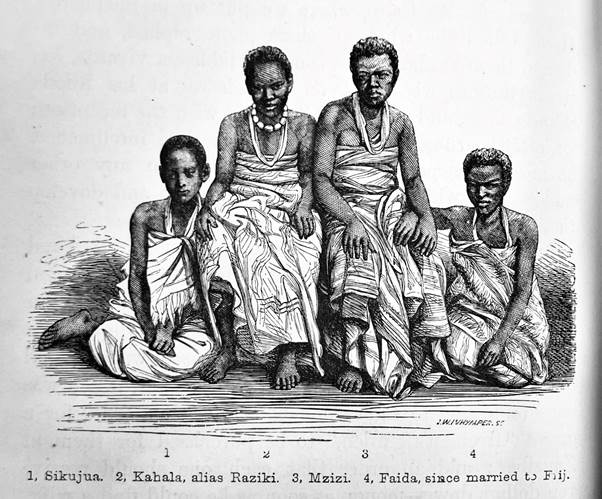

In some ways, Shackleton really was different from most British explorers of the Victorian and Edwardian era. Explorers who travelled to Africa and Asia often employed huge labour forces who did most of the physical work of their expeditions. Richard Burton, John Hanning Speke, and James Grant, who searched for the source of the river Nile in the 1850s and 1860s, employed hundreds of African men who carried their supplies (and often the explorers themselves) into the interior of the continent. They also employed African and Asian men to cook them food and to make and repair their clothes.

Shackleton’s approach clearly differed from that of Burton and Speke, as it required the explorers do much more of the work themselves. But the reasons for this are complex. First, because Antarctica had no Indigenous populations, there were no pre-existing labour forces or transport networks to travel on. The explorers had to do more of the work because there was simply no one they could hire to do it for them. As I examine in my book, strict divisions of labour were often linked to explorers’ gender, class, and racial prejudices. By refusing to do certain kinds of work, explorers in Africa and Asia sought to maintain their position as the thinker and leader of a party.

Shackleton avoided many of these decisions by organising a less diverse expedition. Unlike explorers who had to adapt to indigenous ways of travelling, Shackleton was able to select every member of his expedition from a huge number of volunteers. As a result, everyone who took part was a white man (almost entirely from within the British Empire). Some women did apply to join one of his expeditions but were turned down. Again, this was unusual, in Africa women often formed part of expeditionary parties. We can never know if Shackleton would have adopted the same egalitarian approach if his expeditions had been more diverse, but it seems unlikely.

Yet, Shackleton stands out as different even when compared with other Antarctic explorers, such as Captain Robert Falcon Scott. Like Shackleton, Scott led comparatively homogenous expeditions. Yet he took a somewhat different approach to certain kinds of logistical labour. On his final expedition (1910–13), he employed Thomas Clissold as a professional cook and much of the cleaning and sweeping was done by a “domestic.” Working class men therefore did a far greater share of such work.

Scott thought this approach was better than having everyone pitch in, as it allowed officers and scientists to concentrate on their own work without being distracted by logistical matters. But it is worth remembering that when Scott led sledging parties the work of cooking and pulling sledges was more evenly distributed.

Overall, Shackleton did differ from other explorers in his attitude towards logistical work. He got officers and scientists to do more cooking and cleaning than any other explorer I have come across, including other Antarctic explorers. Yet, there were major limits to his egalitarian approach, as only white men took part in his expeditions.