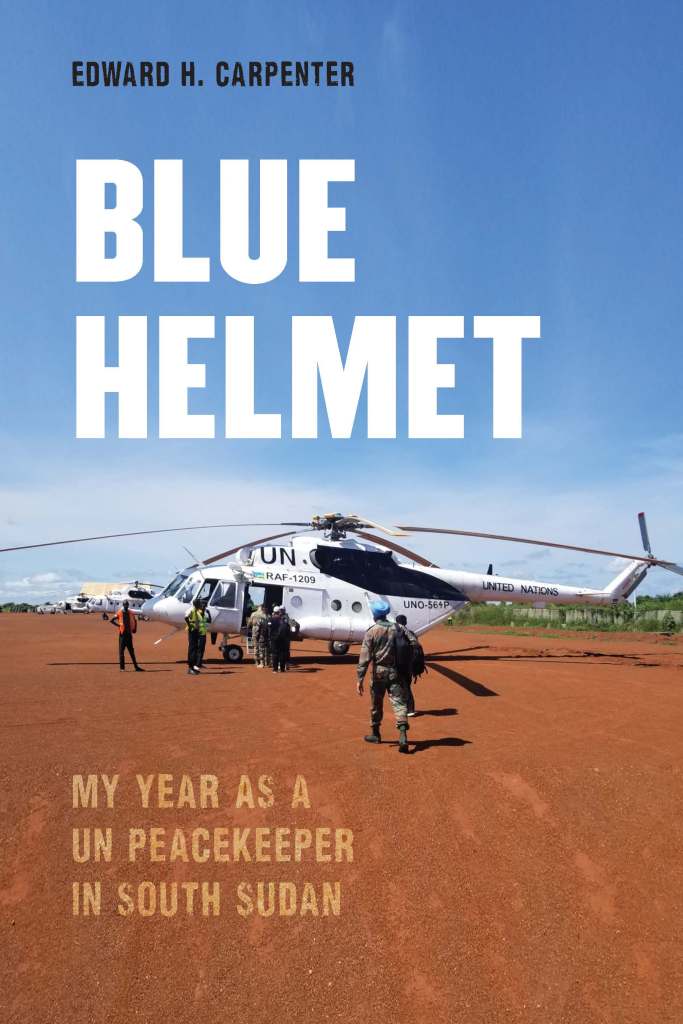

Edward H. Carpenter is the director of World Without War, an NGO focused on eliminating the root cause of the majority of human suffering in the 21st Century. His new book, Blue Helmet: My Year as a UN Peacekeeper in South Sudan, (Potomac Books, 2025) was published this month.

During a recent seminar at the University of Massachusetts in Amherst, I was wrapping up the question-and-answer portion when Grace Delaney posed a question that I didn’t feel I could answer properly given the limited time that we had left in the session.

Her query was deceptively simple: “Based on your experiences in South Sudan, what is your opinion on peacekeeping in general and how effective of a strategy do you think peace operations are?”

That line of inquiry goes right to the heart of my latest book. Blue Helmet is intended to help readers construct their own answers to those questions by showing them what a day, a week, a month, or a year looks like from the perspective of a peacekeeper, painting a vivid picture of what we did, what we didn’t do, and the consequences of our choices to take action—or to allow evil to triumph by doing nothing.

But Grace had asked for my thoughts—and there’s probably never been a better time to share them publicly, as peacekeeping options are proposed for Ukraine, the Sudanese Civil War continues to rage, and UN missions have been attacked in South Sudan, Lebanon, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Simply put, I am a believer in the power of UN peacekeeping missions—with the caveats that the military components of such operations must be appropriate to the situation, that they must be both empowered and required to act decisively to protect civilians and enforce their mandate, and that their leaders must be held accountable if the mission consistently fails to deliver results.

Sadly, as I learned in South Sudan, those caveats are rarely met despite the positive examples set by the successfully concluded missions in Côte d’Ivoire and Liberia. With that being said, it is rarely too late to adjust the makeup and number of peacekeeping battalions and observers, to empower them to act, or to replace leaders who fail to deliver results, so I am hopeful that our current and future peacekeeping operations can be made more effective.

Authorizing a UN peace operation can be a useful strategy for the international community to end the deaths and destruction associated with both intrastate and civil wars, but only if the mission is staffed and operates as I’ve described above, and if there is a serious political effort to resolve the fundamental issues at the root of the conflict. Armed peacekeepers can create a space for political resolutions, but they are not a substitute for serious diplomacy.

The easiest way to explain what I mean by “serious diplomacy” is to provide an example of where that political element has been completely lacking. In South Sudan, the UN and international community have aided and abetted a political solution to create a coalition government between two frenemies, President Salva Kiir and First Vice President Riek Machar—men known to have been personally responsible for crimes against humanity, including the massacres in Bor (1991 and 2014) and Juba (2013 and 2016).

Endorsing a government headed by men whose body counts exceed those of Slobodan Milošević and Radovan Karadžić suggests a lack of sincere intention to form a peaceful, stable multi-ethnic country. Sadly, this example is just one among many: Sudan, Gaza, and Ukraine have now joined Haiti, the DRC, and the Central African Republic as other locations where the deployment of peacekeepers can only serve as a stopgap measure until the root causes of conflict have been addressed.

Many of those root causes are general in nature—competition for natural resources and political power, historic ethnic animosities, and religious differences—but unique to each country. In South Sudan, the resource is oil, and the sub-state violence is driven by ethnicity. In Gaza, land is the contested resource, while religious identity and political autonomy are the contested ideas.

But all modern conflicts requiring UN peacekeepers have one element in common—the forces on both sides have access to an almost unlimited supply of weapons, often sold at great profit by the very countries whose Permanent Member status on the UN Security Council is intended to make them the guarantors of world peace.

So, while I believe that UN peacekeeping can be effective, as an international-level strategic tool in particular, I think we should stop using it merely as a post-conflict bandage to be applied to bloodied and traumatized populations. Where conflict is currently occurring or has just ceased, peacekeepers are a good tool—but I am reminded of the old adage that “an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.”

Prevention, in this case, means sharply curtailing the supply of weapons and cash to both state and non-state actors; it means analyzing where the impacts of climate change will hit soonest and hardest in order to deploy aid and development preemptively, and it means identifying political actors whose actions (perpetrating crimes against humanity on elements of their own population or that of neighboring states) are inconsistent with the UN’s principles and core documents.

Such leaders—whether they are the heads of powerful nations like Russia and Israel, failing states like South Sudan, or failed states like Sudan must be indicted by the ICC, and all the instruments of international power must be levied against their countries in a situationally-appropriate fashion to force compliance with international norms.

During my year in South Sudan, I saw what happens when peacekeeping goes wrong—what happens when there is no accountability for military and political leaders in both the host nation and the UN mission for the atrocities they commit, and the ones which they do not act to prevent.

Yet I also saw what happens when peacekeeping is done right—schools and bridges built, military forces used to help vulnerable populations instead of exploiting and oppressing them. It is those latter observations which give me the hope that we can do peacekeeping better in the future, and the energy to work towards making that happen.