Edward H. Carpenter is a retired lieutenant colonel, a veteran of America’s “Long Wars” who served in the U.S. Army and Marines for a total of twenty-nine years, from Afghanistan to Japan, Indonesia to Saudi Arabia. He has written for the Washington Post and is the author of Steven Pressfield’s “The Warrior Ethos”: One Marine Officer’s Critique and Counterpoint. Carpenter is the founder of the nonprofit organization World Without War, to which he is donating his royalties from Blue Helmet: My Year as a UN Peacekeeper in South Sudan (Potomac Books, 2025).

Blue Helmet: My Year as a UN Peacekeeper in South Sudan tells the story of a country, a conflict, and the institution of peacekeeping through the eyes of a senior American military officer working on the ground in one of the most dangerous countries on the planet. South Sudan is rich in natural resources, and its fertile soil could make it the breadbasket of East Africa. Yet it remains the poorest and most corrupt country in the region, plagued by disease, famine, and ethnic strife. Abductions, sexual violence, death, and displacement affect tens of thousands of people each year.

Edward H. Carpenter pulls readers into his world, allowing them to experience the powerful, poignant realities of being a peacekeeper in South Sudan. In the process, the author reveals how the United Nations really conducts its missions: what it tolerates and how it often falls short of achieving the aims of its charter—equal rights, justice, and economic advancement for all people—with the use of armed forces limited to serving those common interests by keeping the peace and preventing the scourge of war. It is a story that is eye-opening, unsettling, and always compelling.

1. The Worst Day

Only the dead have seen the end of war.

— George Santayana

10 April 2019. Our mission—to visit a government official at his country estate to gain insight into human rights violations reported in the area—was fairly routine. Traveling in a pair of white sport utility vehicles (SUVs) with a local doctor as our liaison and wearing the traditional blue helmets of United Nations (UN) peacekeepers, we passed through the first several checkpoints with ease. These roadblocks were a ubiquitous sight in this war-ravaged nation. They were usually manned by police or soldiers in and around the capital, but out here in the countryside, the guards wore the mismatched uniforms characteristic of the local militia. We weren’t hassled for bribes, but once we were asked for food. “As’eef,” I said in my poorly accented Juba Arabic. Sorry. The man shrugged and waved us on. As we approached the turnoff for the official’s residence—a big house set in a wooded area about a quarter mile off the main road—we passed through a checkpoint that was unmanned. The circumstance was odd enough that I halted our little convoy and called our headquarters for guidance, which was—unsurprisingly—to continue our mission. As we turned onto the narrow dirt road leading into the wooded area surrounding the house, my mind was already moving ahead. Would our contact have the information we needed? How would his armed guards react to a half dozen blue helmets walking up to the door? Would he c—

The improvised explosive device (IED) exploded to our left, shearing the front axle and slamming our vehicle to a halt. Even though my ears were still ringing from the blast, I could hear bullets hitting the right side of the SUV. I shouted, “Bail out left!”

If it hadn’t been for the lessons drilled into me in our pre-deployment training, I would have followed my instincts and made my exit in the opposite direction—away from the blast, the fire, and the smoke. Going left was a dice roll, but it was still a better choice because the vehicle gave us a little more protection from the incoming rifle fire.

A quick count of the team confirmed my four peacekeepers were up—alive, uninjured, and returning fire. Our helmets and body armor had done their jobs. The doctor was not so lucky; his body had been thrown clear of the vehicle and lay a few feet away, his left leg partially severed. Blood was soaking his shirt from some upper body trauma. I had no idea what exactly.

I shouted at the team to lay down covering fire, grabbed my buddy Mack, and sprinted toward the doctor. He was not a small man, and the weight of his unconscious body, slick with blood, defied our first attempt to lift him. Forced to settle for an undignified drag, we managed to get him back to the cover of the vehicle, where we put a tourniquet on his leg and strapped him to a stretcher made of flexible plastic that could be hauled across the ground.

Kneeling over our doctor-turned-patient, I also realized that we were outgunned and running low on ammunition. I had already handed both of my extra magazines to the other peacekeepers who were still returning fire. This wasn’t supposed to be happening. We were here as observers, and most of our colleagues traveled unarmed. We Americans, Canadians, Australians, and Germans were the only ones who carried weapons, which were nothing more threatening than pistols.

Bullets continued to hum through the air above us and smack into the side of our vehicle as we crouched behind it in a slick mixture of blood and sweat. We had to get to a more defensible position and quickly. Frantically scanning for an escape, I glimpsed a house on the other side of the road we’d just left. Shouting an order to pull back, I drew my pistol and led the way at a sprint. Mack and Danny followed, dragging the doctor on the stretcher, and behind them—still firing their pistols toward the muzzle flashes in the trees—came Christopher and Emm.

We made it to the building, cleared and occupied a room, and treated the doctor. We applied a chest seal to plug the wound in his right side; performed an essential, albeit gruesome needle decompression to allow his collapsed lung to expand; and ran a nasopharyngeal airway down his nose and into his throat to help him breathe easier. I had just called for the quick reaction force and a medevac helicopter when I heard our instructors shouting, “ENDEX! ENDEX! ENDEX!” The exercise was over. This “worst day” was just to prepare us for the real thing.

**

Well, it wasn’t quite over. Although we had done many things right, our colonel thought we needed to run through the scenario again. And again. Military training was often repetitive. Even once we had a general idea of what was about to happen, the stress and unpredictability meant that every iteration was different. Someone’s gun jammed, someone twisted an ankle, someone got hit by simulated (sim) munitions and had to be treated as a casualty. And of course, as we got increasingly tired and frustrated, the same exact exercise became even harder.

“How long do you think you guys were in the kill zone?” asked one of our instructors, a tall, ex–special forces medic who went by the call sign “Clocktower.”

I looked at the team. “A couple of minutes, tops,” I replied, as they nodded in agreement.

“Check this out,” Clocktower said, and we huddled around his cell phone. We watched the simulated IED blast and saw our vehicle swerve to a stop. Thirty seconds. Watched ourselves bail out, start to return fire, sprint to the casualty. A minute ticked by. Mack and I wrestled with the heavy “body.” We dragged it toward the vehicle. Struggled to get a tourniquet on its leg. Strapped the dummy to the stretcher. Three minutes. Four. At last, we started to move toward the buildings, away from the gunfight. It had taken five long minutes.

Clocktower shook his head. “Five minutes, bro. What the fuck were you thinking?”

**

We finally performed the culminating exercise to the satisfaction of the senior evaluator and headed back to our ready room to shed our gear and clean the paint and powder residue from the sim munitions that we had fired in training. The next time we loaded our magazines it would be with live rounds.

Today’s worst day was over, but it was not the only one we experienced in our month of training prior to deployment. We were treated to simulated mortar attacks, hostage situations, and a staff exercise where a stable, peaceful country began to melt into chaos due to the twin threats of a spreading cholera epidemic and fighting between government and opposition forces. All these exercises were intended to ensure that we were mentally and physically conditioned to survive and lead through the worst things that might potentially happen on our assignments as UN peacekeepers.

This training was conducted by the U.S. Military Observer Group (USMOG), an organization that traced its history to the early days of UN peacekeeping. Lt. Col. Chris Matherne, the director of operations for USMOG, addressed us all during our first day of training in a classroom on the seventh floor of the Taylor Building in Arlington, Virginia. “You’re going to go out and do great work—maybe even earn some medals,” he said. “But a year or two from now, I don’t want to remember any of you. Because there’s only one officer that we remember at USMOG, and that officer is Colonel William Higgins.”

**

Col. William “Rich” Higgins was a rising star in the Marine Corps in 1987 when he was selected to serve in Lebanon as the senior military observer for the United Nations Truce Supervision Organization, one of the UN’s oldest peacekeeping missions.

As he was driving alone on the coastal highway between Tyre and Naqoura in southern Lebanon, his vehicle was stopped at a checkpoint, and members of the Islamist militant group Hezbollah kidnapped him. Higgins remained in captivity for over a year—interrogated, tortured—and his captors eventually executed him. As a result of this tragedy, USMOG was created to ensure that American officers bound for peacekeeping assignments received special training prior to their departure and that their whereabouts were tracked while they carried out their assignments.

Our three weeks of training—“book work” in Arlington, an urban survival and escape practicum, and this “high-risk operator” course—together with our updated equipment, were intended to prevent any of us from ending up like Colonel Higgins.

**

The USMOG commanding officer, Col. Allen J. Pepper, spoke briefly before our classes started in earnest. He warned us to expect a very different level of organization and a slower pace of progress than we might be used to. He also suggested that we should all invoke the “Serenity Prayer” and ask for the courage to change the things we could, the serenity to accept the things we couldn’t, and the wisdom to know the difference.

He also reminded us that going forward, we would be ambassadors for our country. While the United States put a lot of money into supporting the UN’s peacekeeping efforts, it contributed very few military personnel. We would be a distinct minority in each of our missions and often the only member of the U.S. military that any of our peers might ever meet. As such, our colleagues would judge the U.S. military—and Americans in general—based on what they saw of us, and so would the people of our host nations.

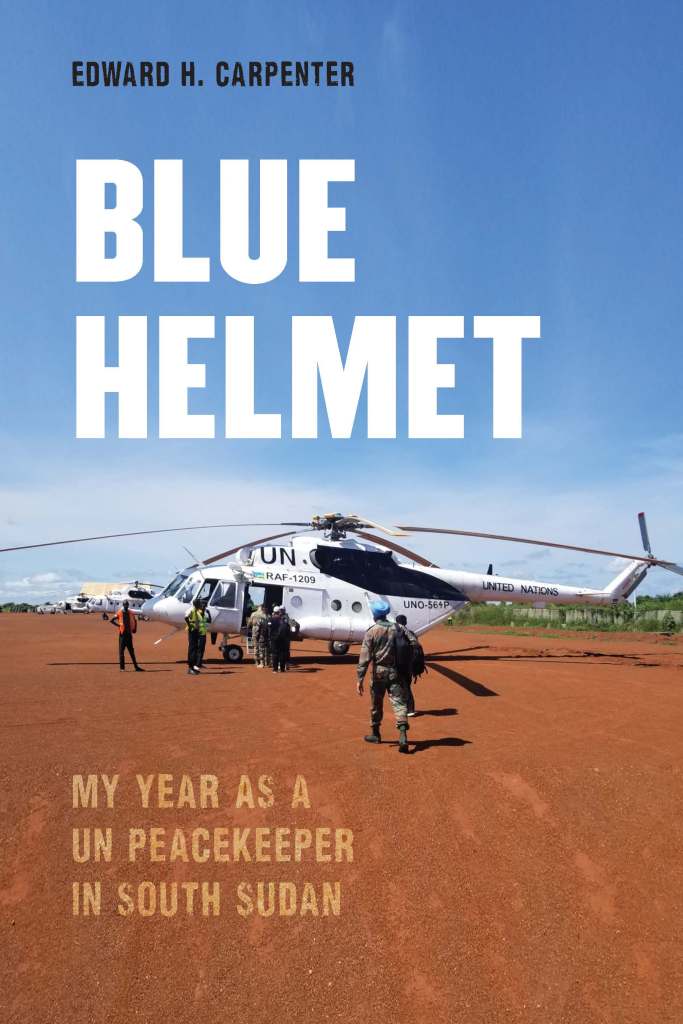

In the big peacekeeping missions, military forces made up the greatest number of UN staff. Its 110,000 soldiers were supported by hundreds of aircraft and thousands of ground vehicles, all of them painted in the universally recognizable color scheme of plain white with “UN” stenciled on them in large black letters. Out of all those familiar blue helmets that one often saw in the media, there were exactly thirty-eight American officers, eight of whom were U.S. Marines. So how did I, out of the all the eighteen thousand officers in the Marine Corps, end up here—just days away from departing for the world’s newest and most dangerous nation?