Michael Dowdy is a professor of English at Villanova University. He is the author or editor of several books, including Urbilly: Poems and American Poets in the 21st Century: The Poetics of Social Engagement, co-edited with Claudia Rankine. His latest book Tell Me About Your Bad Guys: Fathering in Anxious Times (Nebraska, 2025) was published last month.

Ancestors, tell me now if you think I’m tweaking.

—Toro y Moi, “Smoke”

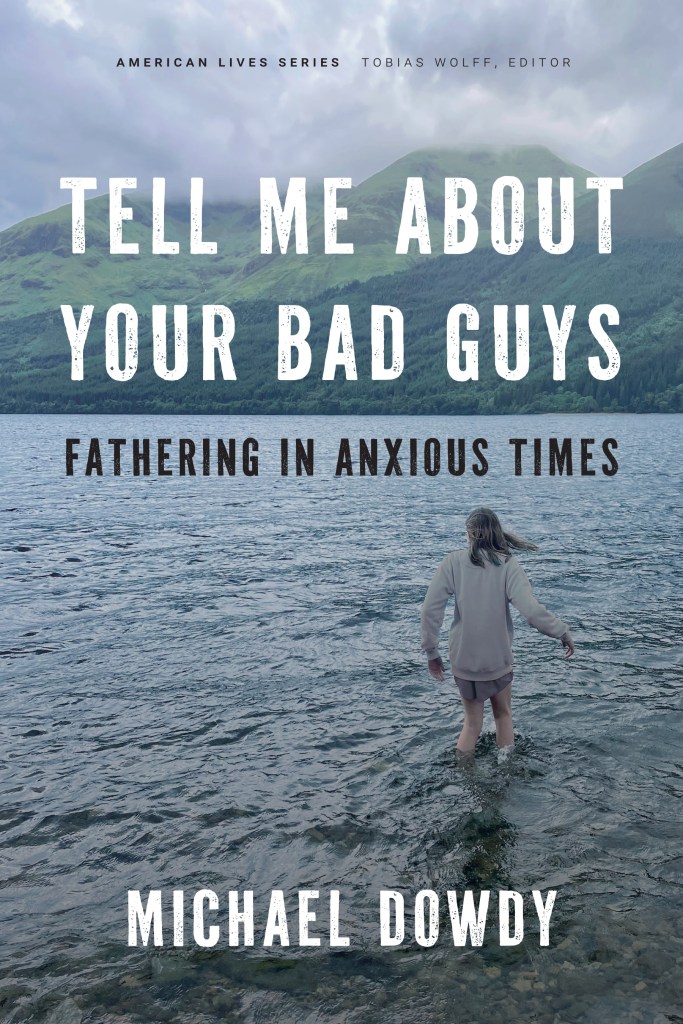

You really put yourself out there. This statement about my new book, Tell Me about Your Bad Guys: Fathering in Anxious Times, was delivered with surprise by the friends and family who know me as a private person. As someone who avoids social media, I certainly didn’t set out to expose my darkest secrets. Now that I find myself alone out here, without my daughter A, the book’s veritable coauthor and my trusty sidekick, I can’t help but interpret this statement as a question: Why did you put yourself out there?

With this question fresh in mind following half a dozen public readings, where I met many anxious dads, I’ve arrived at the idea that fathering is an “out there” practice. In moments of urgency, an engaged fatherhood will become an “out there” condition. If I don’t enter that unnerving land of public scrutiny, if I’m not held to account in its blistering light, then I’m not the daughter’s father I want to be. Out here, my private life always has social stakes: for me, my daughter, and our relationships to our ancestors.

In The Afterlife is Letting Go, Brandon Shimoda differentiates between “researching” and “rehearsing” the ancestors. I read Shimoda’s haunting book just before Tell Me about Your Bad Guys was published, too late to rethink my own ancestral rehearsals. The guiding questions of “rehearsing” relate to manifestation and encounter: “Where do the ancestors gather? Where do you go to meet them?” These questions preoccupied me as I met my parents at a Charlotte brewery before my first Tell Me event. They had concerns. They had questions. Most importantly, and to their great credit, they had done the reading.

At the brewery, my father reported that he’d rate my book “7 out of 10” due to his “frustration” with the book’s treatment of his father. My dad’s displeasure centered on his fear that my daughter, his beloved granddaughter and Tell Me’s beating heart, will dislike her great-grandfather, the complicated man I once idolized. To A, my grandfather will likely remain her Denny’s dad, no more and no less; he passed away five years before she was born.

In the days before meeting in Charlotte, I talked with my parents on the phone for hours at a time. We hadn’t done so in years. My no-nonsense, skilled-in-a-crisis mother served as my gentle, easily wounded father’s handler. She told me they had many questions about the book. But, at the brewery, they simply wanted to talk. The ancestors gathered at our picnic table, our conversation launching my parents and me—we who’d rather talk about sporting dramas than personal ones—way out there. I hope that we kept the ancestors alive as the complicated people they were. Their one question? Painfully direct: Did we not do a good job?

The Urban Dictionary defines “tweaking” as “doing something dumb.” I saw Toro y Moi in concert right before my book tour. Toro’s invocation “Ancestors, tell me now if you think I’m tweaking” looped through my head as I drove from Charlotte to Asheville to Columbia. Had Toro’s line wiggled into my ear like the worm of a guilty conscience? Had not writers dished on their families for centuries? Had I not considered the lessons of Family Trouble: Memoirists on the Hazards and Rewards of Revealing Family, the UNP volume edited by one of my favorite writers, Joy Castro?

In Tell Me, I tried to mind offending the ancestors. That’s why I use the poet Anne Boyer’s words as an epigraph: “I’m not writing a scandalous memoir. I’m not writing a pathetic memoir. I’m not writing a memoir because memoirs are for property owners.” Boyer’s use of paralipsis, that cheeky tool of disavowal, signals my discomfort with the forms of memoir, property, and propriety. But I’m guilty as charged. On the back cover, Literary Essays / Memoir screams from the small print.

It’s fair to conclude that Tell Me about Your Bad Guys puts me out there. But it’s often my daughter who pushes me. The book’s title was her bedtime demand for me to narrate my moral universe when she was three-years old. To her tremendous credit, she also pulls me back with encouragement, forgiveness, and humor. I’m telling myself now that I chose to put myself out there in Tell Me to avoid putting her out there. She doesn’t belong here until she comes of her own volition.

“What does your daughter think of the book,” the scholar Erica Abrams Locklear asked after my reading in Asheville. I spent many more hours stressing over this question than I did worrying about what my parents would think. This imbalance explains my decision to withhold my daughter’s name, to redact her words in our Taylor Swift letters (“Swifties [Redacted]”), to preserve space for her to tell her own story. All while writing my dad’s father and my mom’s mother with a tough love that they may have recognized as my inheritance.

A, I hope that one day you will decide that I did as good a job as my parents did. In the meantime, daughter, tell me now if you think I’m tweaking.

One thought on “From the Desk of Michael Dowdy: Ancestors and Anxious Dads”