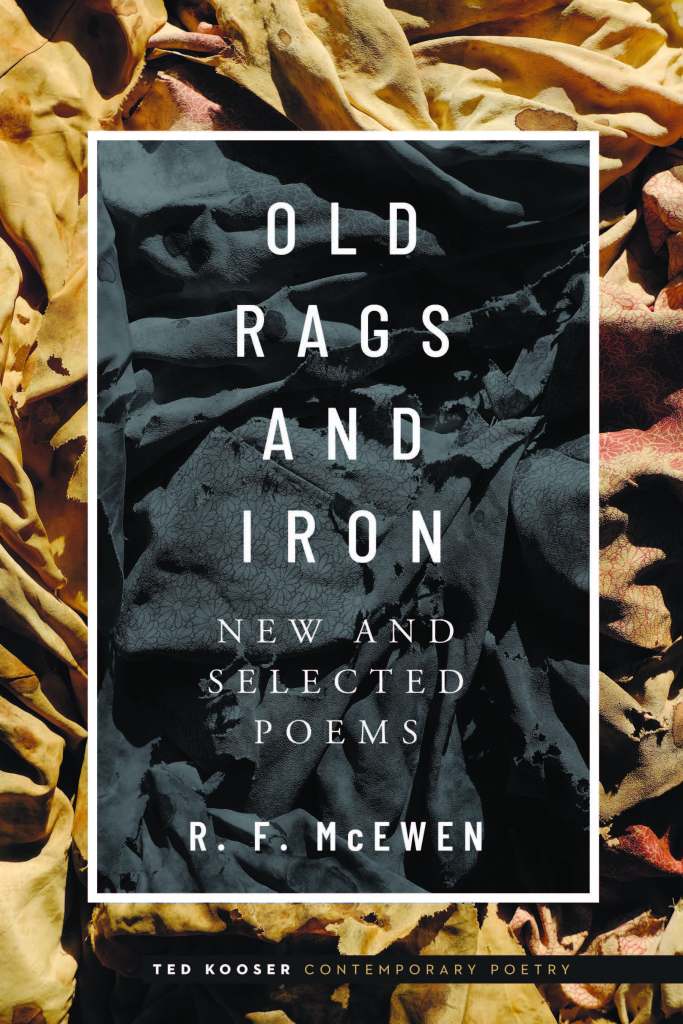

R. F. McEwen was born in Chicago, Illinois. Since 1962 he has been a professional logger and tree trimmer, and he has taught English in Chadron, Nebraska, since 1972. McEwen is the author of several books, most recently The Big Sandy, Bill’s Boys and Other Poems, and And There’s Been Talk . . . His newest poetry collection, Old Rags and Iron: New and Selected Poems (Nebraska, 2025) was published in March.

Old Rags and Iron is a collection of narrative poems about the life experiences of working-class people with whom the author, R. F. McEwen, is not only acquainted but whose lives he has shared. McEwen supplemented his income as a teacher while working as a professional logger and tree trimmer, and he writes with great love and respect for blue-collar families.

Set primarily in the back-of-the-yard neighborhood of South Side Chicago, where McEwen grew up, as well as Pine Ridge, South Dakota, western Nebraska, Ireland, and elsewhere, the poems celebrate many voices and stories. Utilizing tree-trimming as a central metaphor, these poems of blank verse fictions reverberate like truth.

Cotton Bishop’s Good Sheep

The buzzards circled and the sky was gray.

My uncle Bradley set the stock against

his cheek, and still the buzzards circled and

the sky was gray. “You’ll have to try again,”

my mother called. She’d quit the truck and walked

to where we stood. “You think I won’t,” I heard

him whisper as he sent his round to home

within the lamed buck’s brain. “Goddamn these traps,”

he said. “Why can’t you have your father set

them farther from the fence?” “Goddamn these deer,”

she said. “You’d think they’d know to watch the place

beforehand where they planned to set their feet.”

I watched the buzzards’ circling; I watched

my uncle crow-step down the hill then draw

his knife and gut the deer. The wind was calm.

And when my uncle finished with his knife,

he called for us to bring the truck around

the lightning-riven cottonwood that spanned

the short side of the draw. It took them both

to load the deer. I saw the buzzards settled in

a stand of tangled oaks and turned away.

We drove the creek bed till it disappeared,

then crossed the northwest pasture to the road.

Then at my uncle’s, where I fell asleep

against the wood box near the stove, I dreamed

about the buzzards watching while we hauled

the carcass past the gate. The sky was clear.

Lion’s Head

Cass County, Nebraska, 1953

I found a lion’s head in our backyard:

it was a gnarly, flea-forgotten thing

from which it seemed his majesty had fled

into the forest rising to the right

of where we butcher hogs, three hundred yards

(not more), just where our forty ends, just there,

and where spring lightning’s hit in multiples

of ten each fourteenth year, stripped more than one

of Walter Evenhook’s black walnuts bare

and riven cottonwood and oak alike.

I don’t suppose the lion’s had much say

on anything of consequence for quite

some time. “The Serengeti’s not a lark,”

Walt reckons, “not from here.” His mystery’s mine.

And yet some say there was a time big cats

were tearing carcasses and drinking blood

just where our corn is tasseling and dry.