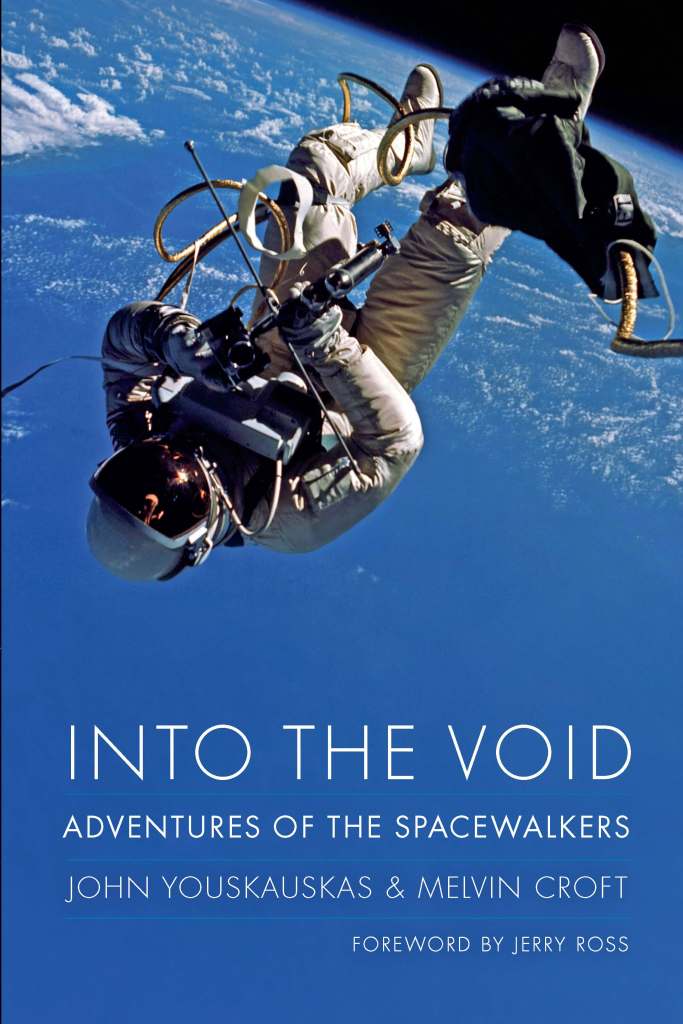

Tomorrow is Spring National Astronomy Day, so now is a good time to spring into space . . . books. To celebrate, we’re sharing an excerpt of the latest title in our Outward Odyssey series Into the Void: Adventures of the Spacewalkers (Nebraska, 2025) by John Youskaukas and Melvin Croft.

Into the Void tells the unique story of those who have ventured outside the spacecraft into the unforgiving vacuum of space as we set our sights on the moon, Mars, and beyond.

John Youskauskas is a commercial pilot for a major fractional jet operator with more than thirty years of experience in flight operations, aviation safety, and maintenance. Melvin Croft has more than forty years of experience as a professional geologist and is a longtime supporter of the Astronaut Scholarship Foundation. Youskauskas and Croft are coauthors of Come Fly with Us: NASA’s Payload Specialist Program (Nebraska, 2024) and contributors to Footprints in the Dust: The Epic Voyages of Apollo, 1969–1975 (Nebraska, 2010).

Introduction

Astronauts are inherently insane. And really noble

— Andy Weir

Among the extremely small sliver of Earthlings who have left the planet for low Earth orbit and ventured out to the vicinity of our closest celestial neighbor—the moon—spacewalkers are an even more elite subgroup of humanity. It is estimated that in all of time, more than 108 billion human beings have inhabited the planet called Earth. Of the nearly 700 travelers who have left Earth to journey into the heavens, fewer than 300 have had the unique opportunity to exit the safety of their life-sustaining spacecraft and float in the vast emptiness of outer space.

Although no real “walking” ever occurred, the press coined the term space walk to describe to the world the technological achievements of Russia’s Alexei Leonov when he first exited his spacecraft in 1965 and American Edward White when he followed suit three months later. NASA’s official jargon used to describe such endeavors outside the spacecraft was extravehicular activity, better known by its three-lettered acronym EVA. The term applies to any activity undertaken exterior to the cabin, be it in orbit, during interplanetary coast, or on the surface of another celestial body either with or without an atmosphere. But aside from the fourteen EVAs conducted on the lunar surface in one-sixth gravity, every other EVA to date—the main subject of this book—has been undertaken in weightlessness.

Upon opening the hatch of their spacecraft, American and European astronauts, Russian cosmonauts, and now Chinese taikonauts find themselves in a bizarre world. Space is devoid of everything supportive to human life. Oxygen, air pressure, and water are present only in unmeasurable traces. Without any medium to propagate the tiny pressure disturbances that are sound waves, space is absolutely silent. While heat and cold exist in the extreme, gravity is seemingly absent, offset by the centripetal force created by the incredible speed of the spacecraft around the planet. As it and everything with it falls endlessly over a horizon that continuously curves away from it, the resulting orbit leaves the spacefarer floating without any resistance, like a swimmer in water with no viscosity. It is a world of nothingness.

Yet in this strange alien environment, a human’s eyes and brain, genetically programmed over millions of years to operate in the gravity of a solid surfaced planet, can adapt quickly to operate effectively in raw space. Despite the overwhelming beauty, enormity, and uniqueness of the universe engulfing them when they first emerge from their spacecraft, spacewalkers are able to push aside the distractions, thanks to intense and ever more realistic training on the ground. There is no one perfect method to recreate a space walk on Earth, no “zero gravity room” in which to train. So the challenge for them is to take each of the individual, imperfect pieces of simulation and mentally blend them into one experience. Even then, the learning curve for a rookie spacewalker is steep once out of the hatch.

The first spacewalkers of the 1960s entered uncharted territory. As earth bound theory became spaceflight reality once they exited their spacecraft, they abruptly realized that their abbreviated training had inadequately prepared them to work effectively. With time, experience, and many lessons learned, the true art of walking and working in space was mastered. The Americans and Soviets, the only space players in town during the 1960s, both had their sights set on conquering the moon, and placing boot prints on the lunar surface required a space suit that could withstand the harsh extremes of the vacuum and temperatures of space, keep their occupants alive, and facilitate exploration. And that space suit and the knowledge of how to function inside it had to be fully fleshed out before a landing on the moon could be attempted.

The space walks performed by Leonov and White in 1965 were much less choreographed and structured than those of modern-day spacewalkers, and the amount and type of preparation for the early space walks pales in comparison to that of today. Not only did the early astronauts have difficulty maintaining control of their bodies outside the spacecraft during EVA; they also often became overheated by the constant exertion in their efforts to maintain stability. EVA has evolved into a complex, procedural, step-by-step process honed over six decades, not only to accomplish useful work after they climb out of the airlock but also to ensure the astronaut’s safe return to the spacecraft’s life-sustaining artificial atmosphere. Gemini astronauts Gene Cernan, Michael Collins, and Dick Gordon, who all struggled with their space walks and failed to complete their assigned objectives in the mid-1960s, likely would have marveled at the long and exacting space walks carried out today on the International Space Station (ISS).

In the aftermath of their lunar programs, both the Soviets and Americans shifted their focus to space stations in low Earth orbit. Mission objectives brought forth new justification for EVA—both the U.S. Skylab and Soviet Salyut space stations required external inspections and repairs. The U.S. space shuttle was conceived with simple EVA contingency plans that evolved into dramatic satellite captures and repairs—such as regular servicing of the Hubble Space Telescope—spectacularly iconic jet pack flights, and construction of the ISS. In a time when the limits of what could be accomplished by spacefarers working in space were being tested, nothing seemed impossible. Surprisingly, although improvements have been made in both the American and Russian suits, new EVA space suits haven’t been utilized in nearly four decades. Thus, spacewalkers have had to adapt to the aging suits as new challenges were conceived.

A modern-day space walk is an all-encompassing exercise in intense focus and professionalism. Zipping along at an astonishing five miles per second, spacewalkers are all business, unlike fictional Hollywood portrayals of spacewalking astronauts, like Matt Kowalski in the popular sci-fi movie Gravity, cartoonishly gallivanting around the outside of the space shuttle as if on a joy ride. An EVA is considered a plum assignment for an astronaut, and with Mission Control, the crew, and the world watching your every move, the pressure to perform is palpable. Nobody wants to be the one who fails. It’s like being an athlete on the spot in a world championship game for nearly seven hours straight.

Venturing outside a spacecraft, while breathtaking, is potentially deadly. Micrometeoroids and the space junk orbiting Earth that has accumulated over the past sixty-plus years have the potential to strike a spacewalker and compromise their space suit. These tiny projectiles have been striking the ISS for two decades now, leaving its exterior pockmarked with tiny metallic impact craters and sharp edges that threaten to tear a pressurized glove or suit. If not immediately fatal, even a slow leak of the suit’s precious atmosphere could result in death. And yet against all these odds, we’ve never lost a spacewalker in space.

To read more about space and the history of spaceflight check out last year’s National Astronomy Day Reading list or Outward Odyssey: A People’s History of Spaceflight!

Thank you for this inspiring and profoundly human article filled with wonder.