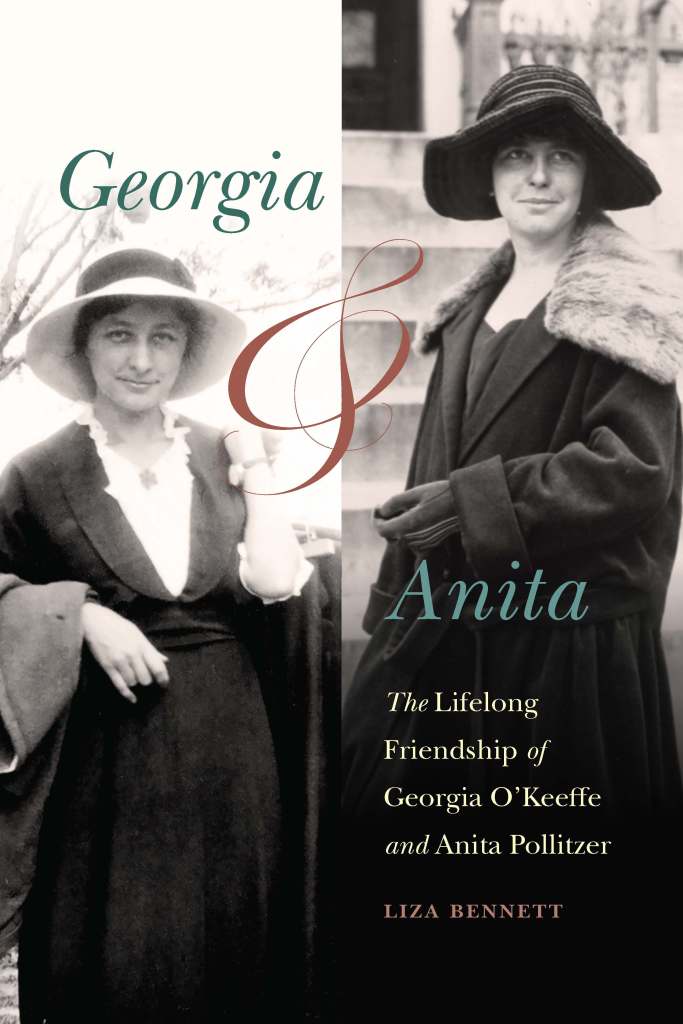

Liza Bennett is a full-time writer and former advertising executive. She has published ten novels, including Local Knowledge, So Near, A Place for Us, and Bleeding Heart under the name Liza Gyllenhaal. She divides her time between New York City and the Berkshire Hills in Massachusetts. Her newest novel Georgia and Anita: The Lifelong Friendship of Georgia O’Keeffe and Anita Pollitzer (Nebraska, 2025) was published last month.

In Georgia and Anita Liza Bennett tells the little-known story of Georgia O’Keefe and Anita Pollitzer’s enduring friendship and its ultimately tragic arc. It was Pollitzer who first showed O’Keeffe’s work to family friend and mentor Alfred Stieglitz, the world-famous photographer whose 291 Gallery in New York City was the epicenter of the modern art world. While O’Keeffe, Stieglitz, and their circle of friends were at the forefront of American modernism, Pollitzer became a leader of the National Woman’s Party and was instrumental in the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment, guaranteeing women the right to vote.

Based on extensive research, including their fifty-year correspondence, Georgia and Anita casts light on the friendship of these two women who, in different ways, helped to modernize the world and women’s roles in it.

1

The Charcoals

Did you ever have something to say and feel as if the whole side of the wall wouldn’t be big enough to say it on?

—Georgia O’Keeffe to Anita Pollitzer, Columbia, South Carolina, December 1915

Georgia was crawling around on her hands and knees, the stub of charcoal smearing her thumb and index finger black. Some outside power seemed to be guiding her hand, forcing her to press down so hard on the cheap porous drawing paper that her markings picked up the grain of the hardwood floor underneath. She didn’t care. Technique, framing, balance, harmony—all that she’d been taught—she was letting go. She was unlearning. Undoing. She’d put everything she’d ever done away, along with her watercolors and oils and brushes. No more color. She was starting over. She had to make something raw and true. Something that was hers alone. Time was running out.

The soft humid South Carolina night was warm for December, giving the Columbia College administration an excuse to turn off the steam heat. Georgia was still wearing one of the simple white shift dresses she’d sewn herself and laundered by hand every week. Solitary and aloof, she sensed she was an object of curiosity among the other teachers and students. What had drawn someone like her to this rundown women’s college on the outskirts of Columbia? Months into the semester, the rationale for her decision—to have the time and freedom to work on her art while making a living—seemed laughable. She hadn’t realized until after she arrived that Columbia College was a Methodist school, or that it had been hemorrhaging money and students. There was even talk of the place going under. That didn’t keep the college from maintaining its religious values while driving its faculty like field hands. Georgia had never shied away from hard work. It was the narrow-minded orthodoxy that made her feel so defeated. She was sick at heart, she’d written to Anita soon after her arrival. She slogged through her days. It was hard to keep motivated enough to teach her classes, almost impossible to find the stamina to create anything new.

But the campus had emptied out now for the Christmas holidays, and she had the shabby rooms to herself. As everyone was leaving, she’d experienced a wave of madness when she decided she had to take the train up to New York City to see Arthur. She was so close to going, she wrote Anita, she had to force herself to lock her money away so she wouldn’t spend it on a ticket. She’d first met Arthur that summer on a weekend camping trip with a group of hikers in the mountains outside Charlottesville. A political science professor at Columbia University, Arthur was giving a course during the summer session at the University of Virginia, where Georgia had also been teaching. They were soon hiking alone together whenever they could find a chance.

Three years younger than she was, Arthur Whittier Macmahon at twenty-four was already a presence in the world: scholar, professor, activist, sought-after speaker. Good family. Fine education. Brilliant future. Everything she lacked. The father who was a freethinking Christian Socialist. His mother, a strong-willed suffragist. She deflected his questions about her own upbringing. The mildewy stench of the cinder block home Papa had built for the family in Williamsburg, Virginia midway through his parade of failed ventures. The cooking smells that permeated the boardinghouse her mother was now running in Charlottesville. How far they’d all fallen. These were things she kept to herself and had been working hard to put behind her. But she worried that whiffs of the past still clung to her somehow, giving her away.

Self-assured and expansive, Arthur rambled on about himself. He advised her on what she should be reading and thinking. She watched his lips move and let the rise and fall of his words wash over her. She’d allowed his four-day visit to her college over Thanksgiving to unmoor her. She might even be falling in love with him, she confided to Anita, though she couldn’t afford to be. She had to keep her mind free to work. Damn it. Her feet were cramping up. She made herself sit back, massaging her bare toes. This little piggie went to market.

The oldest girl in a family of seven children, Georgia was naturally put in charge of her five younger sisters and little brother. Only her older brother Francis had more stature and say. The O’Keeffe family had been happy once. Even prosperous, for dairy farmers. When she was growing up, her father, Frank, had owned six hundred acres in Sun Prairie, Wisconsin, one of the most fertile expanses in the whole Midwest. Folks called it “the O’Keeffe neighborhood.” Georgia’s father had been a different man then, hardworking but lighthearted, his good fortune spilling over into love for his children. He’d bring them home horehound drops and candy corn. But, in his heart, he was an adventurer. The skin of a buffalo he’d shot as a young man in the Dakotas held pride of place on their living room floor.

The Wisconsin winters could be cruel, and when tuberculosis started cutting down Frank’s three brothers one by one, rumor spread that the O’Keeffe milk had also become infected. Convinced he’d be the next to die, Georgia’s father fell for a brochure promoting the healthy climate of Williamsburg, Virginia, and sold his land for the promise of a better life. But, for Frank O’Keeffe, the grass elsewhere would never be as green as that rolling away as far as the eye could see on the bountiful land the O’Keeffes had called home.

Georgia picked up the piece of charcoal again and drew a zigzag up the length of the soft dark bulbous forms that had flowered earlier under the palm of her hand. Not flowers. Not things. She’d won first prize and a hundred dollars at the Art Students League for her still life of a dead rabbit and copper pot. A Dutch Masters’ painting. Every piece she’d ever done she could identify its inspiration at a glance. Durer. Rembrandt. Marin. Dove. All men, of course. She’d opened herself up to them without thinking, allowing their influences to seep into her being. She had not only tried to emulate them, she’d also yearned to please them. That had to stop. She’d never get anywhere if she didn’t learn to please herself first.

The charcoal was soft and giving. She shut out every other thought and let her hand guide her—a river curving along the swollen embankment, or maybe it was the length of a body. Pale and undulating, the shape pressed against the darkness of the encroaching shoreline. Arthur’s arm around her waist. Georgia’s lips brushing across his chaste forehead. Cool against the warmth of her skin, a heat she couldn’t control. She and Arthur had tramped and tramped through the woods. She’d told him she was glad he finally knew how reckless and foolish she could be. With the edge of her eraser, she gently outlined the zigzag of the mountain ridge and highlighted the unstoppable flow of water and longing.

How many days had she been at this? The drawings were piling up. She’d forgotten all about Arthur. She was going deeper, tapping into something new and enthralling, something she had no words for. Feelings became shapes. Black and white contained all the colors of the rainbow. She had never felt so alone—or so free. She was startled to realize she was talking out loud to herself. She thought she might be going crazy, she wrote to Anita. All the great artists were raving mad, Anita wrote back, urging her on.