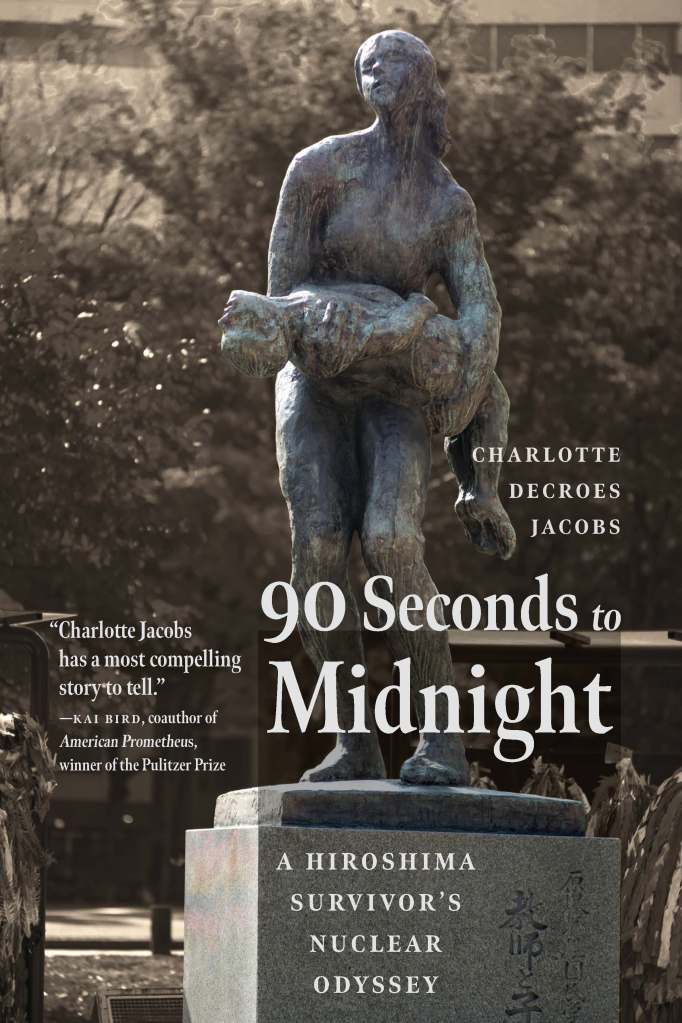

Charlotte DeCroes Jacobs is a professor of medicine emerita at Stanford University. She is the author of two critically acclaimed books, Jonas Salk: A Life and Henry Kaplan and the Story of Hodgkin’s Disease. Her latest book 90 Seconds to Midnight: A Hiroshima Survivor’s Nuclear Odyssey (Potomac Books, 2025) was published in June.

90 Seconds to Midnight tells the gripping and thought-provoking story of Setsuko Nakamura Thurlow, a thirteen-year-old girl living in Hiroshima in 1945, when the city was annihilated by an atomic bomb. Struggling with grief and anger, Thurlow set out to warn the world about the horrors of a nuclear attack in a crusade that has lasted seven decades.

In 2015 Thurlow sparked a rallying cry for activists when she proclaimed at the United Nations, “Humanity and nuclear weapons cannot coexist.” With that, she shifted the global discussion from nuclear deterrence to humanitarian consequences, the key in crafting the landmark Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons. Regarded as the conscience of the antinuclear movement, Thurlow accepted the 2017 Nobel Peace Prize on behalf of the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons. With the fate of humanity at stake and with the resolve of her samurai ancestors, Thurlow challenged leaders of the nuclear-armed states. On January 22, 2021, the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons went into effect, banning nuclear weapons under international law.

Critical historical events need a personal narrative, and Thurlow is such a storyteller for Hiroshima. 90 Seconds to Midnight recounts Thurlow’s ascent from the netherworld where she saw, heard, and smelled death and her relentless efforts to protect the world from an unspeakable fate. Knowing she would have to live with those nightmares, Thurlow turned them into a force to impel people across the globe to learn from Hiroshima, to admit that yes, it could happen again—and then to take action.

Prologue

When she reached the base of the mountain, she found an army training ground the size of two football fields packed with thousands of dead and dying. The air reeked of burnt flesh. What she saw stunned her: strips of skin hanging like ribbons, bones sticking out, stomachs burst open, people charred beyond recognition. Earlier that morning a bomb had struck her city just as she was to begin decoding messages for the Imperial Japanese Army. Buried in a grave of rubble, she had miraculously escaped from a burning building, in which twenty-seven of her classmates were incinerated. A soldier urged her and two other surviving girls to flee to the hills above the city. Her name was Setsuko Nakamura; she was thirteen years old.

All she could see in every direction was a bloodbath. An eerie silence was broken by moans and pleas for water. Setsuko didn’t call out for her parents or sit at the edge of the field covering her eyes to blot out this scene from hell, waiting for someone to rescue her. Instead, she found a stream nearby. With no buckets or cups to carry water, she directed her two classmates to tear strips from their blouses, soak them in the cold stream, then rush back and place the wet cloths over the mouths of the wounded. As they sucked the moisture Setsuko provided, they gazed up at a mere girl—calm, not terrified—who was focused on their comfort. She managed not to recoil at the blood oozing from gashes on heads and chests, hair singed to stubble, lips so swollen that the water dribbled over them. In some the nose, mouth, and ears appeared to have melted together like lava, eyes peering out from a mass of flesh. Sometimes she couldn’t distinguish men from women. People who may have been her neighbors or the local grocer or a revered teacher didn’t look human. Some held their intestines in their hands. A mother cradled a small, blackened mass.

Setsuko scanned the training ground, searching for a doctor or nurse. She found none. The three girls continued to run back and forth to the stream. What else could they do? When the dark clouds lifted, fierce sunlight seared the already blistered bodies. Setsuko couldn’t move fast enough to quench the crowd’s collective thirst. All around her a multitude of stricken people seemed to be waiting for their agony to end. Yet even in the last second of their lives, as she offered water, they looked at her and murmured, “arigato” (thank you). The staring gaze of death followed.

At dusk the three girls sat on the hillside, watching their city, Hiroshima, burn. They remained speechless, their grief incomprehensible. Setsuko thought briefly about her family, but the possibility that they had met the same fate as those around her was too painful. How could Setsuko not be paralyzed with grief when at dawn she saw nothing where Hiroshima used to be? Although she was just a young teen, from somewhere deep inside her emerged a strength that propelled her forward and willed her to hold on. So when the sun rose on August 7, 1945, she stood up, surveyed the unimaginable carnage on the ground below, and pressed on.

Out of the ashes of Hiroshima emerged a young woman who had lost almost everything except her indomitable will. She would vow to her family and classmates slaughtered by the first atomic bomb: never again. She would go on to speak on the world stage and command the attention of international leaders in her lifelong quest to abolish nuclear weapons. It was an arduous journey, and the odds were against her. Setsuko Nakamura was born into a family of samurai origin. Meaning “those who serve,” samurai embraced a code of conduct emphasizing devotion to the common cause and fearlessness in the face of the enemy. These tenets contributed to her fortitude and a spirit that would guide her actions throughout life. This is her story.