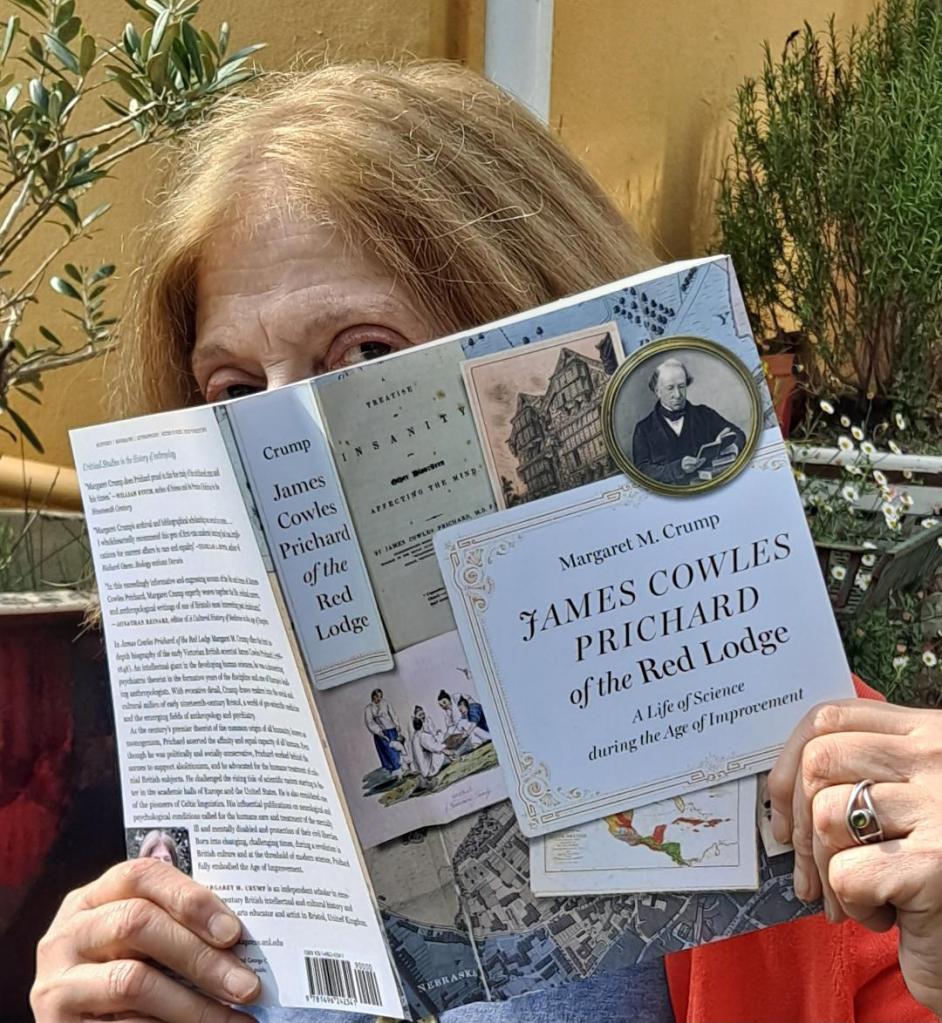

Margaret M. Crump is an independent scholar in nineteenth-century British intellectual and cultural history and works as an arts educator and artist in Bristol, United Kingdom. Her new book James Cowles Prichard of the Red Lodge: A Life of Science during the Age of Improvement (Nebraska, 2025) was published in June.

Below Margaret Crump describes some of the challenges of hunting down the man behind the science in her newly-published biography . . .

James Cowles Prichard was an early Victorian giant in the developing human sciences. A product of a revolution in British culture and at the threshold of modern science, this Bristol physician was renowned as not only the founder of the British discipline of anthropology, but the prime psychiatric theorist of his era and one of the founders of modern Celtic linguistics. He contributed to other disciplines, as well, and was noted as the greatest British scientific anti-racism advocate of the nineteenth century. His name eventually faded from the annals of science, however. To restore Prichard to his place in the history of science, I decided to write not merely an ‘intellectual biography’ analysing his varied contributions to science, but a comprehensive account that would uncover the person behind the science in the context of the culture of his era and, importantly, in terms of science as it was then understood. In historiographical lingo, I hoped to both contextualise and avoid presentism.

Prichard proved elusive. His son’s efforts to produce a handy Victorian ‘life and times’ came to nothing. Then an 1860 newspaper article described a disastrous fire in a warehouse in which Prichard’s scientific papers were likely stored while a large batch of Prichard family documents had become fodder in a WWII paper drive. His life would have to be reconstructed by other means.

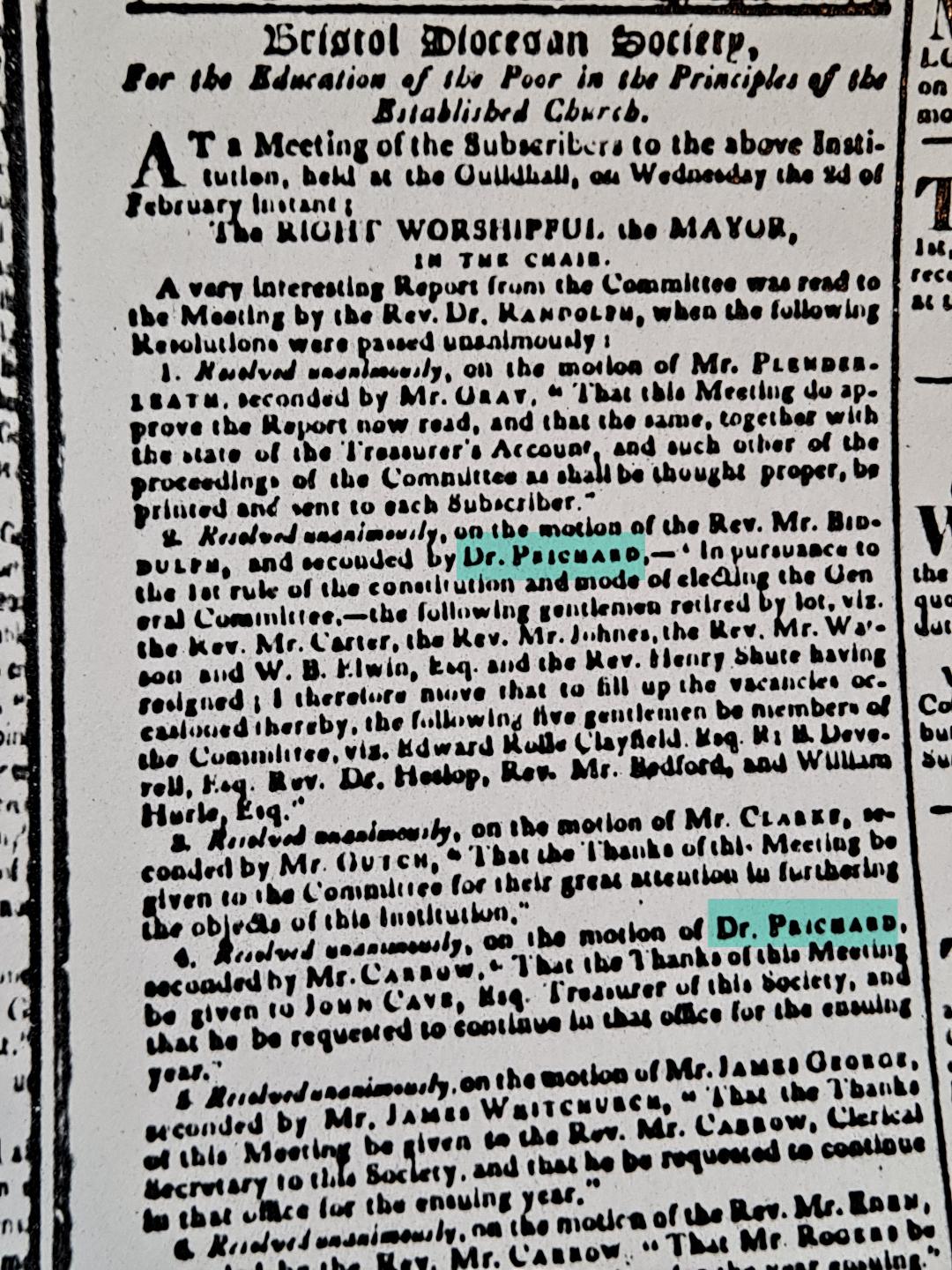

My late partner and I mined personal information about Prichard from a broad range of sources. First, a great deal of genealogical research led us to his many scattered descendants whose attics around England and Wales provided precious, and some not so precious, material. One gem was a manuscript family memoir, volume two of which was owned by a north Wales descendant while volume one was later found among the possessions of a Bristol branch of the family (fig. 1). Then there were a few years spent combing published obituaries; the archives of institutions in which he was involved; the biographies and personal papers of his friends, associates and rivals; accounts of the meetings of societies he attended; records pertaining to his duties as a government official; and the Bristol newspapers (fig. 2) spanning his medical career there—to name just a few. Institutions around the Atlantic world, from a former East German state archive to the Library of the University of Iowa, yielded up odd bits of correspondence. Armed with a mass of facts, there were still some serious gaps to plug.

Reconstructing Prichard’s university career is a case in point. This required the synthesis of facts, inferences, and context. Most tangible is his actual medical degree from the University of Edinburgh in 1808; his certificate is in the Bristol Archives, as is that of his membership to the Royal Medical Society of Edinburgh. But how did he spend the three years of his life there? What was it like being an Edinburgh medical student? The first volume of Prichard’s manuscript memoir contains his pious Quaker father’s letters warning of the perils of the liberal ‘Athens of the North’ and vetoing a proposed summer holiday jaunt to Constantinople. (It is like listening to one side of a telephone call with an errant son.) What was so dangerous about Scottish Enlightenment-tinged Edinburgh education?[i]

A picture of Prichard’s student life emerged piece by piece. The University of Edinburgh Library contains the register showing which books he borrowed and his printed Latin MD dissertation on the unity of the human species. In its archives his name can be found in some of his professors’ registers of fees paid for attending particular courses, so here were some solid facts about which courses he took and when, but what about the content of these lectures? The manuscript ‘Laureations’ marks his graduation, while his signing a special sheet of affirmations indicates he had not yet resigned from the Society of Friends.[ii] Facts.

Next, a host of primary and secondary sources allowed inferences to be made. A fairly contemporary ‘how to’ book lists the qualities a medical student must possess and explains Edinburgh’s medical curriculum and the ideal behaviour of a student. An anonymous little volume by one of Prichard’s professors outlines each course in great detail and even provides a recommended reading list. Obituary memoirs describe his professors and their pedagogy, while contemporary (or near contemporary) fellow students’ manuscript lecture notes furnish further contextualising details. The Royal Society of Medicine’s archives hold the manuscripts of some of Prichard’s rather verbose student essays and its minutes record his participation in the running of the society, including involvement in a bit of a row.[iii] In the RSM’s membership lists are the names of his lifelong friends.

As for Prichard’s day-to-day life from 1805 to 1808, fellow students’ letters and memoirs describe study habits and bemoan the bitter winter weather, high cost of living in Edinburgh, dodgy sanitation, a scarcity of cadavers for dissection, bedbug-infested lodgings, overcrowded lecture theatres and some gruelling and not so gruelling final examinations. A student magazine points the finger at landladies of questionable morality. One young Cumbrian student’s tales of woe include amazement at how his money seems to slip through his fingers at an alarming rate. (Some things never change.) The name of Prichard’s landlady can be found in a local street directory while an Edinburgh newspaper describes some hangings. Modern secondary sources supplied further material, for instance, on the influence of Scottish Enlightenment philosophy and Scottish attitudes towards medical education.[iv]

In synthesising all the manuscript and published, primary and secondary material into a coherent description of Prichard’s university life, I tried to leave readers in no doubt as to what is factual or inferred. Take one sentence containing several facts followed by an inference: “James was among the nearly 250 students attending the course in obstetrics in the autumn of 1806, but he skipped its clinical lectures as he had apparently acquired practical experience in midwifery at Dr Pole’s.” In other words, the class list shows he took the course and how many others did so while his name is not on the clinical lecture list. I can only suppose that Prichard gained practical experience with his pre-university tutor, obstetrician Dr. Thomas Pole where his education was broadly scientific as the content of his course of lectures (fig. 3) and a manuscript memoir of his son John Pole indicate.

Instead of producing a standard ‘intellectual’ biography, I think I managed to set Prichard’s life firmly in the context of Regency and Early Victorian culture. I enriched a mass of facts gathered from a wide variety of sources with inferences and contextualising detail to lead readers into James Cowles Prichard’s life of science. At 666 pages, it has turned out a big read (fig. 4).

[i] M. D. Certificate of James Cowles Prichard, University of Edinburgh and Certificate creating James Cowles Prichard a member of the Edinburgh Society of Medicine, Documents relating to James Cowles Prichard and Augustin Prichard, of Red Lodge, Park Row, Bristol, Bristol Archives, UK, 16082/1a and b; Prichard, J.C. (1847) ‘A Memoir of the Late Thomas Prichard Esq. of Ross, Part 1’, property of the Orton family.

[ii] Examples: Hope, T.C., Class List [for Chemistry 1806–1826], Special Collections, University of Edinburgh Library, UK; University of Edinburgh, Record of University of Edinburgh Laureations and Degrees, 1587–1809, Special Collections, University of Edinburgh Library, UK.

[iii] Examples: Parkinson, J. (1800) The Hospital Pupil: or An Essay Intended to Facilitate the Study of Medicine and Surgery, London: Printed for H. D. Symonds; Johnson, J. (1792) A Guide for Gentlemen Studying Medicine, at the University of Edinburgh, London: Printed for G. G. J. and J. Robinson; Prichard, J.C., ‘Of the Varieties of the Human Race’, Royal Medical Society Dissertations, Royal Medical Society of Edinburgh, UK.

[iv] Examples: Tyson, B. (1991) ‘A Cumbrian Medical Student at Edinburgh University in 1806–7’ in Transactions of the Cumberland & Westmorland Antiquarian & Archaeological Society, 91, pp. 199–211; Chitnis, A.C. (1968) ‘The Edinburgh Professoriate, 1790–1826, and the University’s Contribution to Nineteenth Century British Life’, PhD dissertation, University of Edinburgh, UK.

This contribution is based on Margaret Crump’s article ‘Disparate Measures: Reconstructing the Life of Physician, Psychiatrist and Anthropologist James Cowles Prichard’, due for publication in the September edition of The Historian, the magazine of the Historical Association – the UK’s voice for history. Publications: The Historian / Historical Association