Regna Darnell is Distinguished University Professor of anthropology emerita at the University of Western Ontario. She is the author of History of Theory and Method in Anthropology (Nebraska, 2022), among other books. Wendy Leeds-Hurwitz is professor of communication emerita at the University of Wisconsin–Parkside. She is the author of Rolling in Ditches with Shamans: Jaime de Angulo and the Professionalization of American Anthropology (Nebraska, 2005). They are editors of Invisible Contrarian: Essays in Honor of Stephen O. Murray, the latest title in the Critical Studies in the History of Anthropology series.

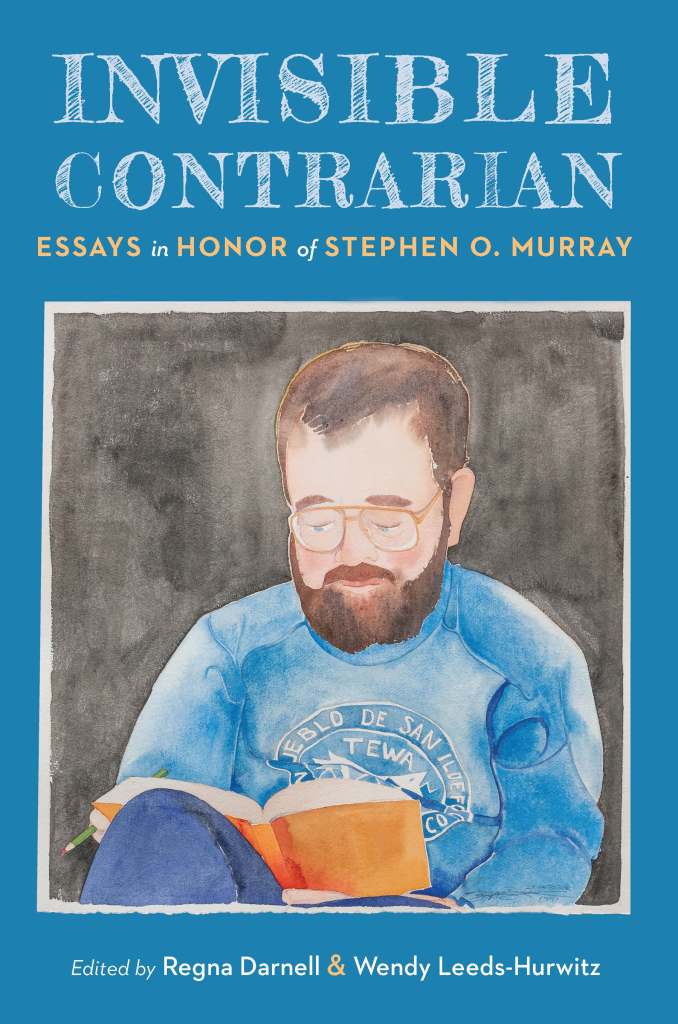

In Invisible Contrarian Regna Darnell and Wendy Leeds-Hurwitz have assembled scholars to memorialize and celebrate the late Stephen O. Murray (1950–2019), who did pioneering research in ethnolinguistics and anthropology of gender and homosexuality. Murray’s wide-ranging work included linguistics, regional ethnography in Latin America and Asia, activism, history of anthropology in relation to social sciences, and migration studies.

Along with a complete list of his publications, Invisible Contrarian highlights Murray’s methodological innovations and includes key writings that remain little known, since he never pursued a tenured research position.

Introduction

Stephen O. Murray as Invisible Contrarian

This book memorializes and celebrates the prescient vision and interdisciplinary contributions of the late Stephen O. Murray (1950–2019), whose ways of practicing anthropology continue to provide a cogent example of an emergent, forward-looking approach that attends to multiple points of view in its broad range of work, which includes linguistics, regional ethnography, activism, migration studies, and the history of anthropology and the social sciences as a whole. In addition, it highlights Murray’s methodological innovations, includes some of his own little-known work, and provides a complete list of his publications as an appendix. Anyone who has contributed as much over as long a period as Murray did deserves reexamination and sharing with contemporary and future audiences.

The book grew out of a panel at the American Anthropological Association convention in the fall of 2022. All of the contributors knew Murray well, most of us for decades. This book should be of interest to anyone who shares one or more of Murray’s interests, whether in disciplinary history, sociolinguistics, regional ethnography, or homosexualities around the world. It serves as a good introduction for those who have not yet read his work; for those already familiar with him, it demonstrates the range of his accomplishments. Many potential readers will have run across one or a few of his publications, given the breadth of his interests, but it is highly unlikely that many will have explored just how much ground he covered. This book makes that obvious and hopes to spur further work in response.

Murray had two major projects: homosexualities (12 books mostly documenting the range of same-sex sexual relations around the world) and disciplinary history (5 books on the history of linguistic anthropology in North America). Yet he published another 7 books on additional topics: 4 can be described as regional ethnography or areal studies, and 3 are related to either fiction (his own, or critique of that by others) or film. For most of us, 7 books could easily represent a life’s work, but for Murray, those books were only evidence of secondary interests. Other topics, such as his original contributions to sociolinguistic analysis, did not result in books but led to book chapters or journal articles. Across all topics he published dozens and dozens of book reviews of the work he read in preparing his own, as well as entries for various encyclopedias and dictionaries, either explaining key concepts or providing biographies of key people. Even the long list of his publications provided in the appendix does not encompass the thousands of reviews he posted online (of books, movies, music, and occasional events)—many of these are included in his journal, some are still available online, and some have been preserved in various collections (mostly his own), but others have now disappeared.

Murray’s Life and Career

We begin by summarizing Murray’s life and career, then return to his published work. He grew up in the town of Blue Earth, Minnesota; his father worked for Standard Oil, and his mother was a teacher, active in her church and the Republican party. He granted them much credit for his efforts, saying, “without my parents’ encouragement, support, and high valuation of education, I would never have written this or any other book” (Murray 1983a, ix). For the BA, he completed a double major at Michigan State University in 1972, the first in social psychology and the second in justice, morality, and constitutional democracy (an interdisciplinary program intended mostly as preparation for law school). Not interested in law school and discovering that “there were no jobs for philosopher kings” (Murray, journal entry, February 19, 2007), he chose sociology for his MA at the University of Arizona, graduating in 1975. That degree was memorable in part for the response from one of his professors to his research proposal on gay men that “no one is interested in your lifestyle” (Murray 2021, xix); as a result, he “did not even think of doing gay research for my dissertation” (Murray 1996a, 277). He left the United States to earn his PhD at the University of Toronto in 1979, again in sociology. He served as teaching assistant and instructor while a graduate student at both Arizona and Toronto, his only formal teaching experiences. He settled in San Francisco in 1978 to write up the dissertation, becoming a postdoctoral fellow in anthropology at the University of California, Berkeley, under John Gumperz from 1980 to 1982, courtesy of a National Institute of Mental Health fellowship. Awkwardly, Gumperz was absent the first year on a fellowship of his own at the Institute of Advanced Study at Princeton; however, in his absence, Murray got to know Gumperz’s graduate students at the time, many of whom were international (for example, Niyi Akinnaso from Nigeria and Amparo Tusón from Spain, both of whom Murray later acknowledged for their support), and with many of whom he maintained lifelong connections. Along with other postdocs and graduate students, Murray (2010a) presented at the American Anthropological Association meeting in 1981, part of a double panel organized by peers Cheryl Ajirotutu and Douglas Campbell, with Frederick Erickson (in education) and Ronald Scollon (linguistics) as discussants. Many of those presentations, though not Murray’s own, were published as chapters in Gumperz’s 1982 collection Language and Social Identity.

Murray specifically mentions that as part of this peer group he was reading work by Gregory Bateson, Erving Goffman, and Alton Becker (in anthropology, sociology, and linguistics, respectively). He also read the work of French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu, whose concept of cultural capital “was a buzz word in this group” (Murray 2010a, 111). With Akinnaso, Murray audited a course offered by the Norwegian anthropologist Fredrik Barth in 1981 and attended lectures by French philosopher Michel Foucault, a visiting professor at Berkeley, in 1980 and 1983 (Murray 2010a, 2012b, 80–87). A subset of the group, “[Ruth] Borker, [Daniel] Maltz, ([Deborah] Tannen, already departed from Berkeley), and I[,] were also interested in genderlects and the relationships between sexuality and language patterns” (Murray 2010a, 110). Of the larger group of peers, he says: “We were immodestly confident that we were studying what was really going on in interaction, and that mismatched interpretive conventions used by speakers from differing backgrounds had important consequences, and, in particular, explained interactional breakdowns, failures of communication, and concomitant reinforcement of intergroup stereotyping in interethnic encounters, especially gatekeeping ones” (Murray 2010a, 110). Together these comments make clear that the postdoc significantly influenced his later research and publications across multiple topics and provided a cohesive group of others with common interests.