Thomas A. Krainz is an associate professor of history at DePaul University. He is the author of Delivering Aid: Implementing Progressive Era Welfare in the American West. His latest book A Great Many Refugees: Progressive Era Assistance in the American West (Nebraska, 2025) was published in July.

Local communities in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries commonly addressed the needs of refugees, defined broadly during the Progressive Era to include internally displaced people and economic migrants. These communities’ efforts to assist people in need created a type of informal pop-up welfare system of short-term assistance that provided for hundreds, and often thousands of refugees.

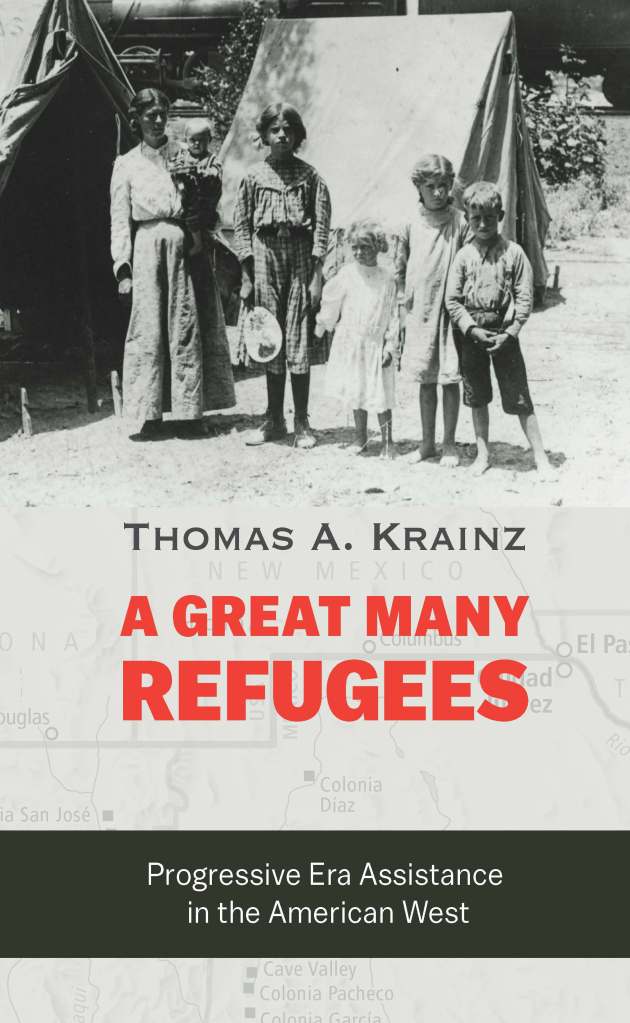

In A Great Many Refugees Thomas A. Krainz examines how communities in the American West cared for refugees. The ten case studies include a range of different causes that forced people to flee, including revolution, war, genocide, environmental disaster, and economic recession. Communities tapped into their local resources to provide for refugees, and this informal welfare proved—in the short term—remarkably efficient, effective, and, at times, flexible and innovative. However, local communities simply could not sustain their widespread relief efforts for long and providing meaningful and comprehensive long-term aid proved a near-universal failure.

Krainz’s examination of how Progressive Era residents cared for refugees uncovers a significant segment of welfare policies and practices that have remained largely obscured. These examples of informal, short-term assistance efforts profoundly challenge our standard depiction of local Progressive Era welfare practices as anemic and unresponsive to those in crisis.

Introduction

When Hurricane Katrina slammed into New Orleans and the surrounding Gulf Coast in August 2005, a debate arose over how to refer to people who had fled the category 4 storm. Tens of thousands of residents had left prior to the storm, and tens of thousands more departed after landfall, many having first been stranded for days in New Orleans or nearby communities. Some media outlets used the term “refugees” to identify people who had fled. Indeed, the large groups of residents carrying what they could or stranded together on elevated roadways looked much like refugees fleeing war-torn areas. The fact that official government assistance went largely missing during the first few days after the hurricane further reinforced the notion that these residents, much like refugees from overseas, were on their own. Other commentators, however, considered the use of the term “refugees” to identify those fleeing Katrina, especially the largely Black and poor residents, as racist. “To see them as refugees,” stated the Reverend Jesse Jackson, “is to see them as other than Americans.” What disturbed Jackson and others was the suggestion that the term “refugee” signified being “foreign,” as if these residents of New Orleans and the Gulf Coast had somehow lost their U.S. citizenship in the storm’s aftermath. “It is racist,” reiterated Jackson, “to call American citizens refugees.”

Jackson and others were implicitly referring to the definition of “refugee” first formalized in the United Nations (UN) 1951 Convention and Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees. Here, the UN spelled out a three-part definition. A refugee is a person who has a “well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion”; who is “outside the country of his [or her] nationality”; and who is “unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to return to” that country. According to this three-part definition, those fleeing Katrina were not refugees because they were not fleeing a fear of persecution, they were still within their own country, and they wanted to return home. Instead, those who fled Katrina would more accurately be categorized as “internally displaced people” (IDPS), if one were using the UN’S definitions and terminology. But Americans have yet to be comfortable with the term “IDP,” and other labels such as “displaced citizens,” “evacuees,” “flood victims,” or “Katrina survivors” seemed awkward and partially inaccurate. In defense of using the term “refugee,” some pointed to its general definition, “a person who seeks refuge,” which did accurately reflect the situation. Still, this dictionary definition was at odds with the common cultural understanding of the term that had become widely accepted because of the UN’S actions. As a result of this disagreement in terminology, no clear trend developed as to what to call those who fled Katrina. The Boston Globe and the Washington Post, for instance, dropped the term “refugee,” while the Associated Press and the New York Times continued its use.

What was missing from these debates was an acknowledgment that the understanding of who is or is not a refugee changes depending on the time period. During the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the term “refugee” had a much more expansive meaning than the UN definition. Progressive Era communities used the term “refugees” for those fleeing a fear of persecution (like the UN definition) and to describe those whom many today would label as IDPS or economic migrants, including those pushed out because of natural disasters (such as fires, floods, hurricanes, tornados, storms, earthquakes, and landslides), economic downturns, or even civil unrest. Some of the people displaced in Chicago’s race riot of 1919, for instance, were referred to as “refugees.” The term was even used during labor disputes. When Arizona mine owners, for example, established a camp to house strikebreakers and nonunionized workers, it was referred to as a “refugee camp,” and when strikers were forcibly removed from Bisbee, Arizona, and abandoned near Columbus, New Mexico, they too were called “refugees,” and their temporary camp was also known as a “refugee camp.” The term “refugees” was widely used to cover an eclectic range of situations. The cause or reason for a group to flee seemed less important to communities in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries than the basic similarities shared among the various groups. Here were people who were often fleeing danger; seeking safety; in need of food, shelter, clothing, and transportation; and often lacking a clear destination. In a sense, the assorted groups that were pushed out by whatever cause or for whatever reason acted much the same and needed much the same assistance, making them all refugees. This all-encompassing notion of refugees from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries will be used throughout this study. Because of this broad definition, it means that addressing the needs of refugees was a common experience for many turn-of-the-century communities.

The ubiquitous nature of refugees seems a bit surprising given scholars’ focus. Like the general public, historians have mainly associated refugees with the post–World War II years, when waves of displaced people entered the United States. Often these refugees came from communist countries, and America’s welcoming of them clearly scored a propaganda victory against the human rights violations and economic failures of communism. “Refugee admissions,” states historian Carl J. Bon Tempo, “struck a rhetorical blow against the Soviets and reminded the world of the United States’ unbending commitment to anticommunism and winning the Cold War.” Tens of thousands of other refugees arrived as a consequence of America’s military wars in Southeast Asia, wars that the federal government justified as stemming the spread of communism. During this same period, however, the American government was far less welcoming of refugees fleeing pro-American dictatorships like those found in El Salvador or Nicaragua. Since the Cold War’s end, America’s conditional welcoming of refugees has further waned, and refugees have become a convenient target for far-right, authoritarian politicians, thrusting refugees into the nation’s heated and ever-expanding culture wars. Despite the groundbreaking work by scholars to provide a historical context for America’s refugee policies, the notion that refugees prior to World War II were not a concern or were few or largely absent still underpins both the literature as well as the public’s understanding.

This invisibility, however, is unwarranted and inaccurate. Our nation’s history is filled with rebellions and warfare, be it against Native Americans, European countries, Mexico, or among ourselves. Each one of these conflicts resulted in refugees, and conflicts in nearby nations also drove people across our borders and to our shores. As mentioned previously, natural and man-made disasters along with civil strife added to the forced migration of people. The displacement of people is by no means a sideshow to our history; in fact, it is deeply woven into our nation’s story. Even though the federal government lacked a robust refugee policy prior to World War II, this does not mean that local communities and governments at the local, state, and even federal levels did not grapple with refugees or policies toward refugees.

This study examines how local communities in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries cared for refugees, utilizing the broad definition of “refugee” from the period. The book, for the most part, follows refugees from their initial arrival in safe locations to the termination of assistance a few days, weeks, or even months later. Often, communities had little, if any, warning of refugees’ imminent arrival, forcing residents to respond quickly to the situation suddenly at hand. Upon their arrival, what almost all refugees immediately needed were the same basic necessities—food, shelter, clothing, and transportation. While in each case it is generally clear when this aid started, the ending of assistance can be murky, as news coverage frequently tapered off or even vanished after the excitement of hundreds or even thousands of newcomers faded. This focus on the tangible benefits, the nuts and bolts of aid, received by refugees grounds the book’s narrative and analytical core. How did communities care for refugees? Who led and funded these efforts? Who did and who did not receive assistance? Why did some get aid while others did not? Who decided who received aid? How much and what type of aid was distributed? When and why was aid ended? Answers to these questions and more flesh out the varied experiences of refugees.