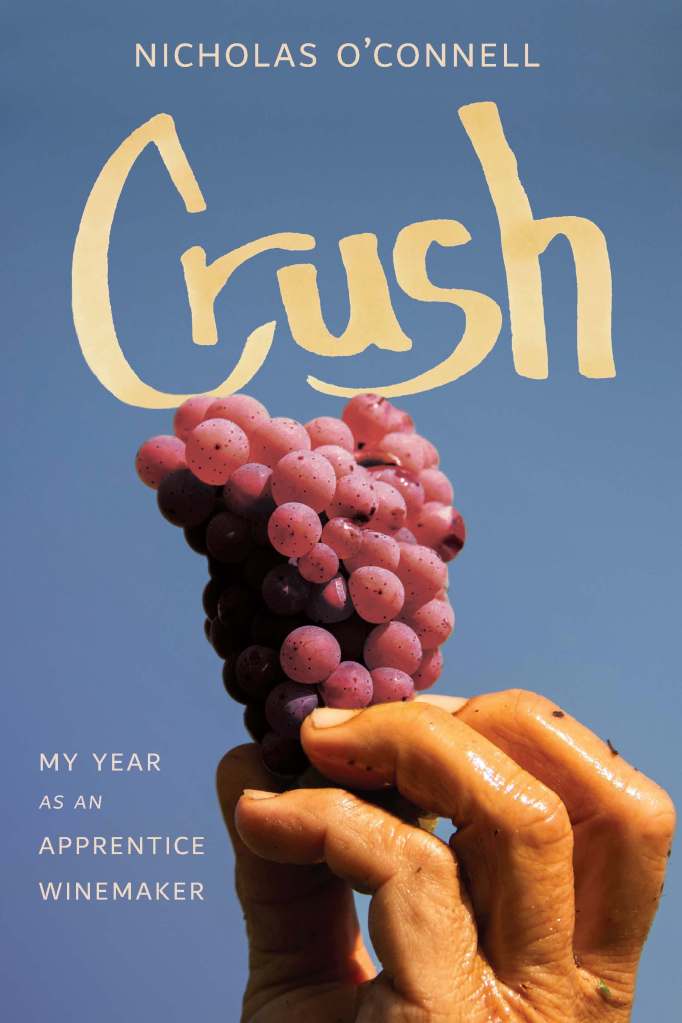

Nicholas O’Connell is based in Washington State and is the founder of the Writer’s Workshop. He contributes to media outlets such as Newsweek, Food & Wine, the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, and National Geographic Adventure. O’Connell is the author of five books, including The Storms of Denali: A Novel, On Sacred Ground: The Spirit of Place in Pacific Northwest Literature, and most recently Crush: My Year as an Apprentice Winemaker (Potomac Books, 2025).

In Crush Nicholas O’Connell provides a behind-the-scenes look at the daily operations of some of the world’s most prestigious wineries on the West Coast.

This insider’s view of the wine world includes the intense competition for the best grapes, the bizarre lingo of the tasting rooms, and the visionary winemakers who magically transform grapes into high-end wine. It is a world that includes not only romance and refinement but long hours, backbreaking labor, mind-numbing repetition, and fanatical dedication to quality. Such devotion resulted in the 1973 Stag’s Leap Wine Cellars Cabernet that won the best red wine at the 1976 Judgment of Paris and transformed the U.S. wine industry.

1

Garagiste

Winemakers call it the Long Haul. It’s a three-hour drive from Seattle to eastern Washington, where the state’s best wine grapes grow. The state’s wineries are largely located on the wet west side, while the vineyards are located on the dry eastern side. Every fall, winemakers make the 180-mile run.

My wine-making partner, or garagiste (garage winemaker), Tom Remmers lends me his ancient Ford F250 diesel, nicknamed “the Beast,” to pick up 1,200 pounds of Cabernet grapes from Ciel du Cheval Vineyard on Red Mountain—one of the finest red wine grape regions in Washington State and arguably the planet. I’d prefer to take my van, which is more reliable, but Tom argues the truck is the better choice for transporting that many grapes.

While I fetch the grapes, Tom prepares for the crush, setting up the big plastic fermenting tanks, cleaning out the stemmer/crusher, and assembling the crew. Timing is critical, with little margin for error, as the grapes need to be crushed as soon as possible after picking. Making the three-hour run should be a seemingly simple task, but nothing about wine making is simple.

The Beast shudders and shakes as I pull out of the driveway. Climbing a modest incline, it shimmies, backfires, and belches a cloud of black smoke. After merging onto I-90, I lean back into the Naugahyde bench seat. I’ve been making this run for fifteen years now, but this is the first time with the Beast. I was reluctant to take it, given its 250,000 miles on the odometer, but Tom encouraged me. “You’ll love it,” he said. “You can have them dump the grapes in the back. You don’t need to put them into buckets.”

This trip is the second of three runs to pick up grapes to make wine for our wine co-op, Les Copains (“the friends” in French). While I love the romance of wine making, I wonder, as do many aspiring amateurs, if I could take it to the next level. I’ve worked for years to gain access to the best fruit, with the famous boutique wineries gobbling up all but a fraction of it. A few years ago, Ciel du Cheval Vineyards (translation of nearby Horse Heaven Hills) agreed to sell to us as I write about wine and so am considered part of the industry. I don’t want to do anything to jeopardize getting fruit from one of the best vineyards in the state, a critical step in making outstanding wine. We’ve won first place awards at amateur competitions. I should be satisfied, but there seems so much more to learn.

After crossing Snoqualmie Pass, the low point in the Cascade Range that vertically bisects the state, I turn south onto I-82, which rises steeply toward Umtanum Ridge. The truck grumbles as the grade increases. I keep my foot on the gas, willing it up the hill. My coffee cup dances along the top of the dashboard. A burnt smell seeps out of the heater. I keep it floored, praying the heap will make it over the top. Black, acrid smoke billows out of the dashboard vent. I open the window and stick my head outside to avoid asphyxiation. I ease up on the pedal, but the smoke keeps coming. Finally, the truck clears the top of the ridge.

I pull off to the side and let the Beast cool off. Leaning against the side panel, I take a drink of water, resolving never to drive this piece of shit again! But I’ve got to get the Beast to Ciel. The grapes are ready. If you pick too early, the grapes taste green and vegetal. If you pick too late, they have too much sugar and produce a strong, alcoholic wine. You have to pick them right on time. Our crew of a half-dozen Les Copains members has already committed to helping with the crush. Turning back is not an option.

With the smoke cleared, I fire up the truck and keep going. The road traverses the undulating brown hills and scabrock country outside Yakima. I keep my foot on the gas, coaxing the Beast up the hills and making up time on the downhill, hitting sixty.

My appointment is at 1:00 p.m. with Ryan Johnson, the manager at Ciel du Cheval Vineyard, located outside of the Tri-Cities. Ciel has produced several hundred-point scores from renowned wine critic Robert Parker Jr., and dozens of others were rated in the nineties over the last decade. Beyond the scores, I consider this my favorite site, with bold, powerful red wines that display balance and elegance, similar to some of the best French wines but with a richer, rounder new-world taste.

I glance at my watch: 12:30 p.m. Right on track. I’m fifteen minutes away from Ciel, the Beast humming along the straightaway.

KABOOM! The truck bucks violently and veers to the right, heading for the ditch. I whip the wheel to the left, overcompensate, and swerve into the passing lane, narrowly missing a truck. I swerve back to the right, tires squealing on the asphalt. The Beast bobs and weaves like a rodeo bull, trying to throw me. Slamming on the brakes, I fight to regain control. Finally, I wrestle it to a stop on the shoulder of the highway.

Breathing rapidly, I look around. What was that? A stray tank round from the nearby U.S. Army’s Yakima Training Center? The cab doesn’t seem to have any physical damage, other than the dregs of my coffee spilled on the floor. I breathe deeply to slow the pounding of my heart. Taking a look to make sure no cars are heading my way, I open the driver’s door and get out. I walk around to the right side of the truck. The right front tire looks as if someone carved it up with a chainsaw. There are scorch marks behind the truck on the asphalt. The smell of burned rubber fills the air.

At the back of the truck, I spot a spare tire underneath the truck bed. The bolts securing it are rusted in place. Damn! I call Ryan on my cell phone.

“I’m going to be a little late,” I say, trying to sound calm. “I’ve got a flat

tire. Is there any place around here that can fix it?”

“There’s a Les Schwab in Benton City,” he says. “Can you get there?”

“I’ll try,” I reply, hoping he’s not judging me a bumbling amateur.

I start up the truck again. The diesel engine coughs and sputters to life. Slowly, I push down on the gas pedal. The Beast lurches forward, making a horrible metallic grating sound as the shredded tire grinds into the asphalt. I keep going, the tire smoking and squealing, a ragged cloud of burned rubber trailing behind. I keep the speedometer at five miles an hour and pray the truck will make it to the Les Schwab station.

Turning off the highway, I head for downtown Benton City. There’s one main street with gas stations and feed stores. People stare as the Beast belches smoke and limps along like a wounded water buffalo. I’m providing the afternoon’s entertainment.

I spot the Les Schwab sign and turn into the lot. A young man greets me and frowns at the tire. “Looks like you need a new tire,” he says enthusiastically.

While he replaces the tire, I walk down to a store to buy a diet soda. I shake my head about the flat; the rubber was probably so old it just fell apart. Would the other tires do the same? By the time I return, he has replaced the old tire. I pay and thank him. Then I rev up the Beast and get back on the highway.

The road to Red Mountain rises above Benton City, passing fields of sagebrush and rusted-out tractors. It looks more like farm country than a world-class vineyard site, but so did Napa Valley thirty years ago. “Welcome to Red Mountain,” proclaims a stone and wood sign of a vaguely old-world design, the only indication I’m approaching a famous viticultural area. Low brown hills rise in the distance, dotted with sagebrush and covered with shattered volcanic rock. Beneath them appear the bright green geometric patterns of vineyards. There are no restaurants, hotels, or wine trains on Red Mountain; the area is as pure and abstract in its undulating beauty as a landscape in Tuscany.

It is just after 2:00 p.m. when I turn right on a gravel road lined with poplars. I’m an hour late, but at least the truck hasn’t broken down again. I pass a Ciel du Cheval sign, a rusted-out truck, and then strict rows of vines with carefully tended clusters of Cabernet, Merlot, and Syrah grapes hanging beneath them, reflecting the perfectionism of owner Jim Holmes and his manager Ryan Johnson. The astonishing Ciel fruit reveals the power and elegance of the Red Mountain region. It’s a wine lover’s idea of heaven.

Rising up from the vines is not a chateau but a large wooden outbuilding, a kind of glorified tractor shed, surrounded by workers. Forklifts ferry bins of grapes to waiting trucks, loading them up for the long haul to the west side. The bins are stenciled with the names of the vineyard’s customers: Quilceda Creek, DeLille, Andrew Will, McCrea Cellars, Cadence, Betz Family, Fidélitas, Mark Ryan—a who’s who of Washington wine. The place hums with order and purpose. The harvest is in full swing.