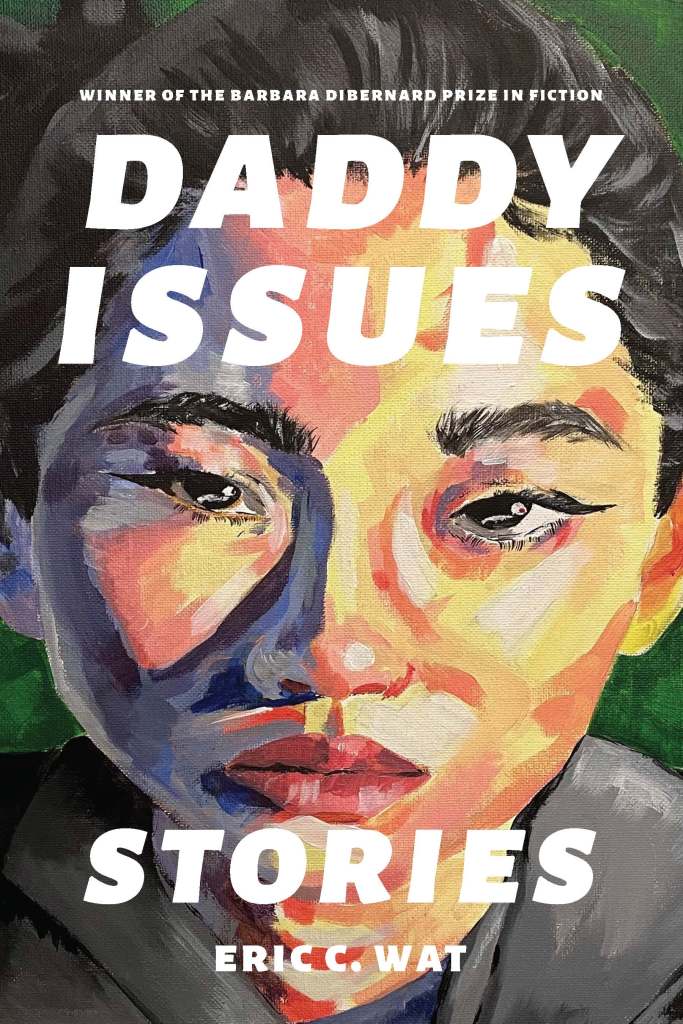

Eric C. Wat is the author of Love Your Asian Body: AIDS Activism in Los Angeles, winner of the 2023 Outstanding Achievement in History Award from the Association of Asian American Studies; the novel SWIM, a Los Angeles Times bestseller; and The Making of a Gay Asian Community: An Oral History of Pre-AIDS Los Angeles. He works as an independent consultant for nonprofit organizations and philanthropic foundations. His latest book, Daddy Issues: Stories (Nebraska, 2025) was published this month.

Daddy Issues is a collection of moving and complex—yet simply and directly told—stories of queer Asian American experiences in Los Angeles. In many of these stories, the protagonists are artists and writers and other creative thinkers living on the fringe of survival, attempting to align a life of the imagination with the practical considerations of career, income, and family: a gay father who hasn’t come out to his young son; a social worker, numbed by the destitution of his clients, who finds himself lost in self-destruction; a trans man who returns home to a father with dementia to help his family pack as they are pushed out by gentrification; a husband who can only stand aside as his wife heals from a miscarriage; and a broke writer who learns to love his stories again.

The stories in Daddy Issues offer different contemplations on solitude—the good and the bad of it. Ultimately, this collection by Eric C. Wat is full of hope, and it shows how we can find the connections we need once we allow ourselves to become vulnerable.

THIS BUSINESS OF DEATH

Because it was Sunday dim sum rush hour, the restaurant put our post-funeral luncheon in the small room upstairs that was usually reserved for the bridal party at a wedding banquet. From the tail end, I saw our people snake through the crowd and din of the dining hall to reach the loft above: generations of noises, waiters hustling with sauces and clean plates, cart ladies hawking their steaming tins on any table where you could still see glass on the lazy Susan. Despite our somber look, we had to stand in wait for these cart ladies to complete their transactions. Finally, we passed the last waiter’s station and then, one after the other, filed up the narrow staircase to our room. At the corner of the room was a bar without any liquor. The couch was pushed against the wall, along with the movable closet where the bride would hang her many changes of clothes. Empty hangers dangled from it. Carton boxes anchored it below. This had been my aunt’s favorite Chinese restaurant in all of San Gabriel Valley when she was alive. They’d managed to arrange five tables in this loft; she would’ve considered it a good showing.

The cart ladies wouldn’t come up. They didn’t have to. On behalf of my cousins, I’d ordered the same set of dishes, eight in all, for every table ahead of time. By the time the soup came, the room was as rowdy as the scene below us. The rest of the dishes came fast and furious, and the eaters devoured them in the same fashion. In another ten minutes, the salt-and-pepper pork chops was just a plate of bones. After dessert (a watered-down red bean paste, pretty much a soup), some guests began to stand up and visit with each other. The waiters brought a stack of Styrofoam boxes to each table for the leftovers.

The host table included the three surviving children, my cousins Ben, Clark, and Eliza (in that birth order); Clark’s wife, Zara, and their two teenage children, twins; and our two uncles, bachelors who had outlived the last woman in their generation. There had been some debate, and in the end Eliza’s boyfriend, Xander, was also invited to that table. When it looked like people wanted to leave, Clark stood up. Eliza followed, and then Ben. They lined up by the door to say thanks and goodbye. I was pretty sure you only did that at weddings. This might be the most matrimonial vestige in the room.

Eliza was collecting envelopes from the departing guests. The way she was clutching them, I could tell she was feeling their heft. My eight-year old son Jeremy looked up between levels of Angry Birds on his iPad and asked me what was in those envelopes. I only had him every other weekend. This was not supposed to be my weekend, but the ex made a rare exception for funerals.

I said it was money.

“Like birthdays?” Jeremy asked.

“Kind of.”

When I had told him about his great-aunt’s death, he took it matter-of-factly, as far as I could tell over the phone. I had a feeling that my ex had already talked to him about it, not trusting me to handle a delicate subject like death with a boy his age. She had a knack about talking to children like they were adults. I was loath to admit that the philosophy came in handy this time. I was off the hook. My vague answer about the envelopes puzzled him more, though not enough to keep him from his game. I let this one go, too, thinking this was not the kind of tradition he would have to worry about.

I looked up at Clark and saw that my aunt’s mahjong friends began to queue up. In the spectrum of guests, I was an in-between, closer to the hosts than other guests but not enough to sit at the head table. I couldn’t leave before other guests, but I wasn’t expected to stay behind to settle the check. While I waited, Clark’s wife, Zara, came to my table and scooted next to me.

“Hey, Jer,” Zara said to my son on my other side. From his iPad, Jeremy looked up at her to confirm the voice’s identity. He did this a lot, at least with people on my side. Sometimes I thought he could tell his mother’s friends by their voices without looking up. He looked at her for three full seconds before he finally said, “Hi, Aunt Zara.” I could see the dark crown of her head, silky strands straightened and cascading down.

“You look taller than the last time I saw you.”

“How would you know? I’m sitting down.”

“Jeremy!” I shouted at him and put my hand on the screen, fingers spreading and covering as much of it as possible. I knew why he said it. He had missed a trick because she broke his concentration. Jeremy had always been a “sensitive” child, as the ex would say. She said “sensitive” like it was a virtue that needed to be encouraged, but Jeremy was not sensitive like empathetic, just easily hurt or irritated. He used to cry readily when life wasn’t turning out as he’d expected; now, he acted out against people with what the ex thought was wit. A wuss with a smart mouth will get himself in a lot of trouble. It was not the kind of thing that a father should think or say (though I had done both). “Apologize to your aunt,” I said.

“I’m sorry.” He wasn’t disingenuous about it. At least he still listened to a stern voice.

“It’s all right. We’re all a little on edge these days.” She reached over and roughed up his hair a little. Jeremy was smart enough to let her, but he still rubbed one in when he turned to me and protested, “But I’m not growing taller.”

“Be patient, kid. You will soon.” For all our sakes, I acted like it was a complaint, not truth-telling. I sensed by now that Zara hadn’t come to my table for company. So I sent my son away. “Go play with your cousins.”

Head down and iPad in both hands, Jeremy went between Zara’s twins, as if he were passing through two redwoods.

I told Zara, “Now your sons. Look at them. They’re much taller than I thought anyone in our family could be. Must be your genes.”

The boys always had dark eyes like their mother’s. When Clark and Zara were dating, she told me that her mother taught her how to put on eye makeup, and nobody knew how to do that better than Arabic women because for centuries eyes were all they could show to the world. Her sons always reminded me of that conversation. The boys had lashes thicker than any of the young men in my school, or many young women, for that matter. Zara usually grew soft when people complimented her children. When I turned to her, I was surprised to find her brows furrowed, making her own eyelashes fan in a beautiful way, delicate by their length and intimidating by their precision.

“Clark told me what happened,” she began hesitantly, “when you were young.”