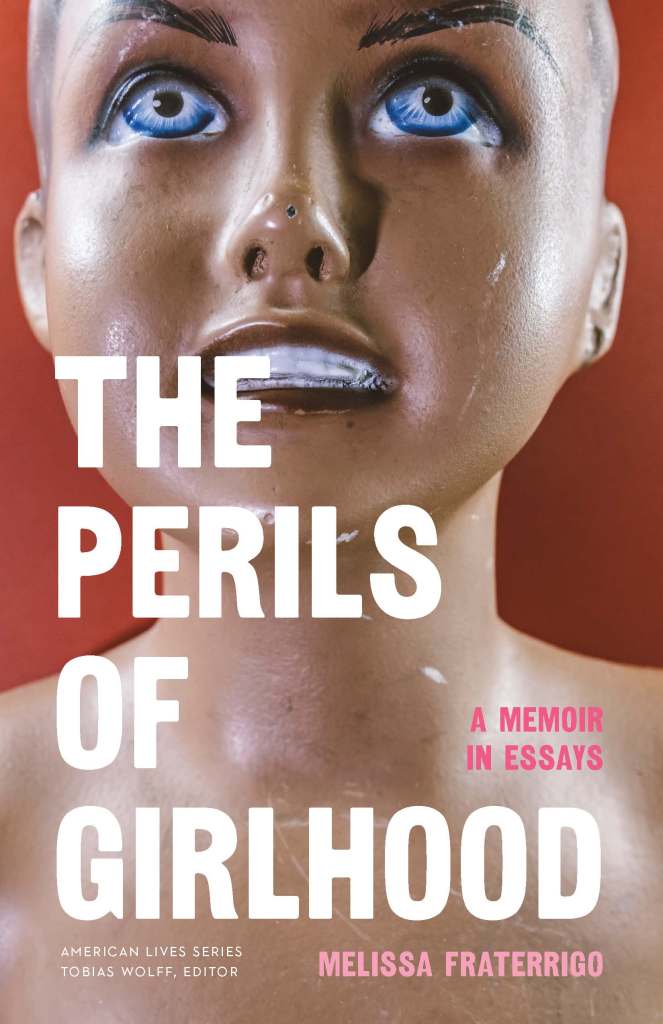

Melissa Fraterrigo is the executive director of the Lafayette Writer’s Studio in Lafayette, Indiana, and teaches at Purdue University. She is the author of the novel Glory Days (Nebraska, 2017) and a collection of short fiction, The Longest Pregnancy: Stories. Her latest book is The Perils of Girlhood: A Memoir in Essays (Nebraska, 2025).

“I don’t even remember what I had for dinner last night,” my sister texts when I send her a photo of the two of us and our brother as kids in a plastic-sided pool in our backyard. In the photo we are on our bellies, propped up on our elbows, our palms glued together. The water is only a few inches deep. “Are we praying?” she asks.

WE’RE PRETENDING TO BE DOLPHINS, I respond.

I can’t believe she’s forgotten.

I don’t know why some things stick in my mind, but for the memoirist, a rich memory offers a lot of material to wade through. I’ve learned to use such “autobiographic images or ‘river teeth’” as essayist David James Duncan calls them to recall moments that beg to be explored. I use such signs to lean closer and investigate.

To write my memoir-in-essays The Perils of Girlhood, I had to work my way into difficult memories by closely examining small, mundane details. I experienced sexual aggression at the hand of a high school date, and to write about it, I used my senses to delve into the memory and then tap into what could be seen and felt. Even from the safety of my current suburban home, I didn’t want to revisit the hotel room where my date led me but found that by reflecting on visual and bodily sensations, I could ground myself in a way that allowed me to move forward. I began by returning to the memory in my mind, listing what I saw, and then selected the details from this list that elicited physical reactions. “His breath rose above him as he talked and time seemed to slow. It was like he was visiting me from another country. I patted my lips and the skin around it, then looked down at my pinked palm. I crossed my arms. Held myself.”

I wrote such a scene through various iterations, working with a kitchen timer for a set amount of time. Those were challenging scenes to write, so once the timer went off, I stopped working and stepped away from my desk.

I needed that reprieve.

Of course, memory can be fallible. Cultural artifacts can combat that and expand a story’s scope.

In “Coach Matt,” an essay that details my teenage crush on my swim coach and how he took advantage of me, I used music to add to the setting and mood of the essay. “Finally, much of the meet had been packed up and Madonna’s ‘Open Your Heart’ played from overhead speakers. A bunch of younger swimmers started pushing each other into the pool, some already dressed. The sun strode high, shattered the water’s surface into tiny pieces of glass. High school classes would start in a few weeks, but now Madonna was singing, ‘If you gave me half a chance, you’d see my desire burning inside of me.’”

I wanted to make sure the story was not just about me and my experience but addressed universal truths. Here Madonna’s song brings in another layer of life in the 1980s with subliminal messages about gender, power, and the male gaze.

A writer must be deeply interested in themselves and the world, but they must also remain open to uncertainty. Often during the drafting process, I asked myself questions. Why did I do what I did? What was I thinking in this moment? And then I worked to integrate such interrogations into the essay draft.

In “Diabetic Vernacular,” the essay that concludes the book, the narrative jostles between the present, as I walk with my high school friend Emily, and the past, when the two of us were teenagers and lifeguards, trying to make sense of the world. Here the word “perhaps” brings in conjecture, allowing me to arrive at a larger understanding. “Many cultures believe that girlhood is something that must end in order to get to the next state. I imagine that many mothers mourn this transition, this giving up and giving away. How many of them, like me, discover echoes of their own childhoods as their daughters grow up? I wonder if perhaps girlhood is something we still carry with us, like the Russian nesting dolls I keep on my bedroom dresser, and that without it, we cannot become women.”

Memories are not fixed. They can be elicited by looking closely at what is uniquely interesting to you and how your own recollection of what was continues to make you today. Even if your own memory is not your strong suit, you can use photographs to elicit your senses, focus on pop cultural artifacts, and pose questions to yourself to tease out what you believe to be true about a moment. Such choices can further memory’s reach and lead to greater understanding in a memoir draft.