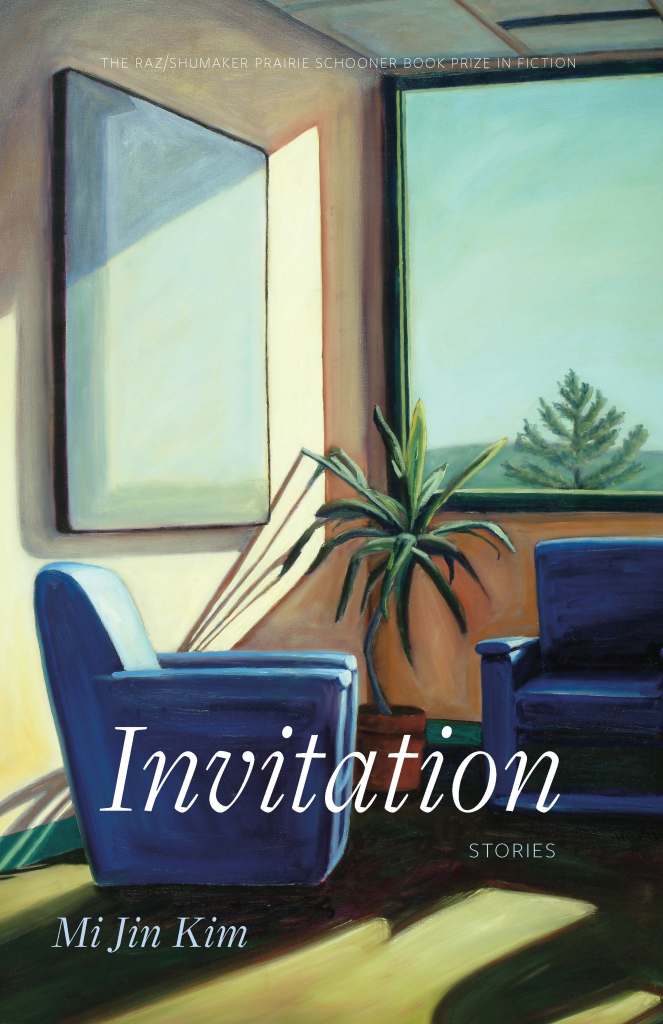

Mi Jin Kim was born in Seoul and grew up in Los Angeles. A graduate of the Helen Zell Writers’ Program at the University of Michigan, her fiction has appeared in A Public Space, Quarter after Eight, and swamp pink. Her new book Invitation: Stories (Nebraska, 2025) is the winner of the 2024 Prairie Schooner Book Prize in Fiction. She lives in rural South Korea with her family.

In Invitation, men and women try and fail to connect to the people they want to be with. As they remember the first people who dominated their lives—parents, best friends, cousins, crushes—they find themselves repeating old patterns. A boy shares seemingly disturbing details about his mother’s disappearance with an aloof tutor. A man stalks an ex-girlfriend but finds her missing. A woman wakes up in an empty apartment—and to every mother’s worst nightmare. When a callous young man penetrates the bell jar of an elderly couple’s quiet life, their live-in assistant learns a cruel lesson about loyalty.

Why are we the way we are with one another? And what do our relationships ask us to become? In these stories, set mostly in South Korea, all must contend with the uncertainty and danger that comes with connection, real or imagined. These stories by Mi Jin Kim ask us to consider what it is we really want from the people we think we need.

1

Acapulco

I knew when Hojun’s mother disappeared, more or less, because she, or someone with her phone, texted back to my question of tacking on an extra 150,000 won to her son’s monthly tuition fee for an international shipment of books we needed and then—nothing. The family was upper–middle class so I felt comfortable billing them like this occasionally, but also I was resentful of them precisely because they were upper–middle class and pretended to me that either they didn’t know, or couldn’t do, something like ordering their own books for the one son they were supposed to be rearing. In this country, such people could pay anyone to do anything for them.

I had seen and interacted in person only with the mother and son but I had a good sense of what sort of father was involved—an older man, probably, someone who didn’t work very much but whose work brought in all the money; his hands-off, distant and indifferent, even willfully ignorant and uninterested paternal style was likely supported by his circle and, of course, this sort of thing was still culturally encouraged. Hojun, as the product of this type of father and the kind of mother I knew the woman to be, had turned out exactly as you’d expect from this grotesque and far too common familial arrangement. He was a humorless and subtly defiant child; to me he was mostly cold and frequently cranky. I found him to be intellectually mediocre, the type of student I would have preferred not to take on if it had been up to me. My friends claim not to understand me when I say this sort of thing, that I truly can’t help but take on any prospective who comes along, but it’s true: I don’t always need the money, and I’d be much better off not working with anyone else’s child. Long after I discovered the truth of what had likely happened to his mother, I became more certain about my stance on odd and unpleasant children and what I should do about them. But at the time, I disliked Hojun from the onset and still agreed to teach him what I could.

The day after his mother supposedly disappeared, he showed up for our tutoring session at seven o’clock. I disliked him even more because he encroached on my evenings in this way while all my other students had nicely open weekends. Only this one had such a packed schedule we had to meet on his Tuesday and Thursday evenings, seven o’clock, and at my apartment because he lived close enough that he could walk over from his luxury town house. I couldn’t eat dinner before he arrived, because then I’d have to floss and brush my teeth before our sessions—but what if I wanted to snack on something later? I’d have to drink tea while he was here, which would stain my teeth if I brushed right before I had my evening cup. After he left it would be too late in the day to sit down to a full meal; ravenous as I was after working with a student, I couldn’t break my diet and hope to keep slim while maintaining such a sedentary life at my desk, in my little apartment, only taking walks when I felt up to sketching in my eyebrows and putting on actual shoes instead of the plastic slippers I wore to take the food waste out to the bins.

I dreaded seven o’clock; twice a week I waited for it to come, pacing on my balcony. That day when he arrived, neither of us knew yet that his mother had left the family. At the end of our lesson, Hojun informed me that she hadn’t been home when he got back from his after-school academy. I didn’t care about the comings and goings of his mother and was annoyed that he thought I would be interested. “I’m sure she’s just busy,” I said, walking him to the door. Hojun was a little fat, which I found suspicious. Usually boys of his class and type were naturally thin, or burned off the expensive fruit and imported milk and high-quality beef their mothers fed them by running around everywhere as soon as they were dismissed from their lessons. A clever child could always surprise me, offer something new that only someone so young and little could notice or think about. But almost right from the beginning, Hojun made our lessons unendurable. He moved slowly and spoke slowly but only when I asked him a question. He almost never answered immediately but only after asking for clarification, because he hadn’t been listening or hadn’t understood though I always spoke plainly to him. I hated waiting for him to speak, but I also hated listening to him when he did.

“See you Thursday,” I said, hurrying him out of my apartment with my eyes. We’d only just ended our lesson but already I dreaded seeing him again.