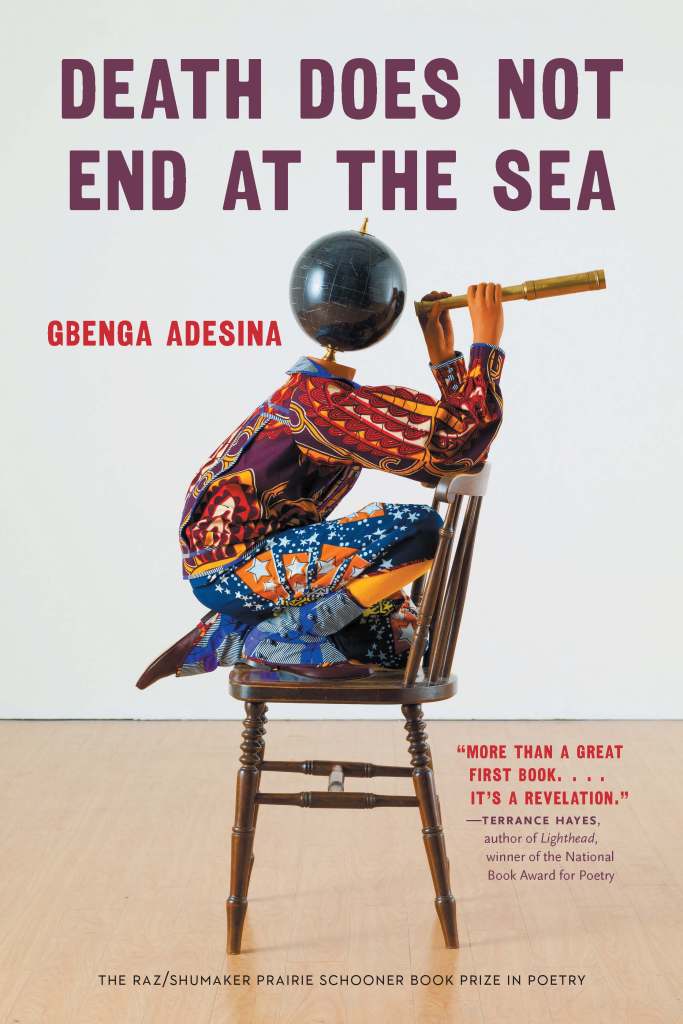

Gbenga Adesina, a Nigerian poet and essayist, is the inaugural Mellon Postdoctoral Fellow in Global Black and Diasporic Poetry at the Furious Flower Poetry Center, James Madison University. He received his Masters in Fine Arts from New York University, where he was mentored by Yusef Komunyakaa. He is the cofounder and editor of A Long House, a journal of diasporic art, thought, and literature. He has won multiple fellowships, and his poems have appeared in the Paris Review, Harvard Review, Guernica, Narrative, Yale Review, The Best American Poetry, the New York Times Magazine, and elsewhere. His book, Death Does Not End at the Sea (Nebraska 2025), was the winner of the 2024 Raz/Shumaker Prairie Schooner Book Prize in Poetry and was longlisted for the 2025 National Book Award in Poetry.

In Gbenga Adesina’s groundbreaking debut book of poems, a defiant and wise exploration of exile, voyages, and spiritual odysseys, we encounter figures embarking on journeys haunted by history—a son keeps dreaming he carried his dead father across the sea; a young Black father, tired of fear and breathlessness, travels with his son in search of the ghost of James Baldwin—to Paris, the south of France, Turkey, and Senegal to investigate his ancestral roots; and finally, a group of immigrants on small boats in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea sing in order not to drown, in a stunning sequence that invokes the middle passage.

In a lyrical voice at once new and surprisingly ancient, Adesina’s Death Does Not End at the Sea explores the complexity of elusive citizenship, an immigrant’s brokenhearted prayer for a new beginning, a chorus of elegies, and a cosmic love song between the living and the dead.

GLORY

Glory of plums, femur of Glory.

Glory of ferns

on a dark platter.

Glory of willows, Glory of Stag beetles

Glory of the long obedience

of the kingfisher.

Glory of waterbirds, Glory

of thirst.

Glory of the Latin

of the dead and their grammar

composed entirely of decay.

Glory of the eyes of my father

which, when he died, closed

inside his grave,

and opened even more brightly

inside me.

Glory of dark horses

running furiously

inside their own

dark horses.

I CARRIED MY FATHER ACROSS THE SEA

He was a child. He was dead.

He was the shaft of a long-tailed astrapia. He was a forest

of bruise. He wore a door on his face.

He wore the black suit

of his wedding. The square pocket

was still full of his vows.

He was light to carry,

his burdens and vows had bled out of him.

He was heavy

with the responsibility of the dead.

What sort of a son

leaves his father

chained to fatherhood?

I lifted and propped him up with my frame.

I measured the length of him with my length.

The feet stuck in sea sand, his weak knees,

his arms gripped my sides.

As the currents rose, the collar on his broken neck

flared into a float.

The gash the surgeon’s knife left on his head

became a halo, it signaled in the dark.

I put my nose to his nose.

I put my finger in his mouth.

I tied his IV tubes, now a human gill, around our waists

and swam in the vein

of the water.

“Look,” a sphinx in the waves said.

“A son carries a father.”

Death is not silence.

It is where I hear you most clearly.

What sort of a son

leaves his father’s body

chained to the dark grievance inside the earth?

I carried my father on my back.

I felt the bracing inside his afterlife heart

on the skin of my spine.

He wore his face as a door

he promised to open to me.

He bled

out his vows.

THE PEOPLE’S HISTORY OF 1998

France won the World Cup.

Our dark goggled dictator died from eating

a poisoned red apple

though everyone knew it was the CIA.

We lived miles from the Atlantic.

We watched Dr. Dolittle, Titanic, The Mask

of Zorro. Our grandfather, purblind and waiting

for the kingdom of God, sat on a throne in his dark

room, translating Dante.

The Galileo space probe revealed

there was an entire ocean hiding beneath a sheet

of ice in Jupiter’s moon.

The Yangtze River in China lost its nerve

and wanted vengeance.

Elsewhere a desert caught fire.

We got a plastic green turtle and named it Sir

Desmond Tutu.

A snake entered our house through the drain

and like any good son, I ran

and hid under the bed.

Google became a thing.

Viagra became a thing.

In July, it flooded at nights and a wind nearly

tore off our roof. I thought God is so in love

with us,

he wants to fill us with himself.

Mother, I saw her through a slit in the door, a glimpse

of amaranth-red scarf and swirling yellow skirt.

She thought no one was looking. She was dancing in a trance

to Fela Kuti. She laughed and clapped

at the mirror. It was the year our house became a house

of boys and girls, and a ghost, our little sister.

Calmaria. That’s what the Portuguese called it. When it rained

and the world was suddenly becalmed, we would run

and peel out of the door, waving at the aurora

of birds flitting past in the sky.

We knew one of them, the little one, used to be one of us,

those spectral white egrets.

At last- a contemporary poet who does not wallow in self pity but is a true visionary through the chaos.