Jason Brown is a professor and director of the Creative Writing Program at the University of Oregon. He has published four books of short stories: A Faithful but Melancholy Account of Several Barbarities Lately Committed, Driving the Heart and Other Stories, Why the Devil Chose New England for His Work (an NPR summer reading pick), and Outermark. Brown has been a Stegner Fellow and his work has appeared in the New Yorker, The Atlantic, Harper’s, The Best American Short Stories, and The Best American Essays and won a Pushcart Prize. His newest book, Character Witness: A Memoir (Nebraska, 2025) was published last month.

When Jason Brown’s mother is arrested for stealing $38,000, he agrees to serve as a character witness for her, hoping to keep her out of prison.

Thus begins Character Witness, a memoir, a chronicle of a mother’s struggle with mental illness, addiction, and poverty, and an inquiry into whether we can escape the legacy of the past. Brown realizes that his troubles as a young man mirrored his mother’s, and as he chronicles how sexual abuse can pass down through generations—from father to daughter, and later from mother to son—he begins to look for answers about whether people can change.

Brown and his mother share a difficult history, but they also share a common sense of humor and a sense of the absurd. More than simply a recovery narrative, Character Witness centers the necessity of staying with loved ones even in their worst moments.

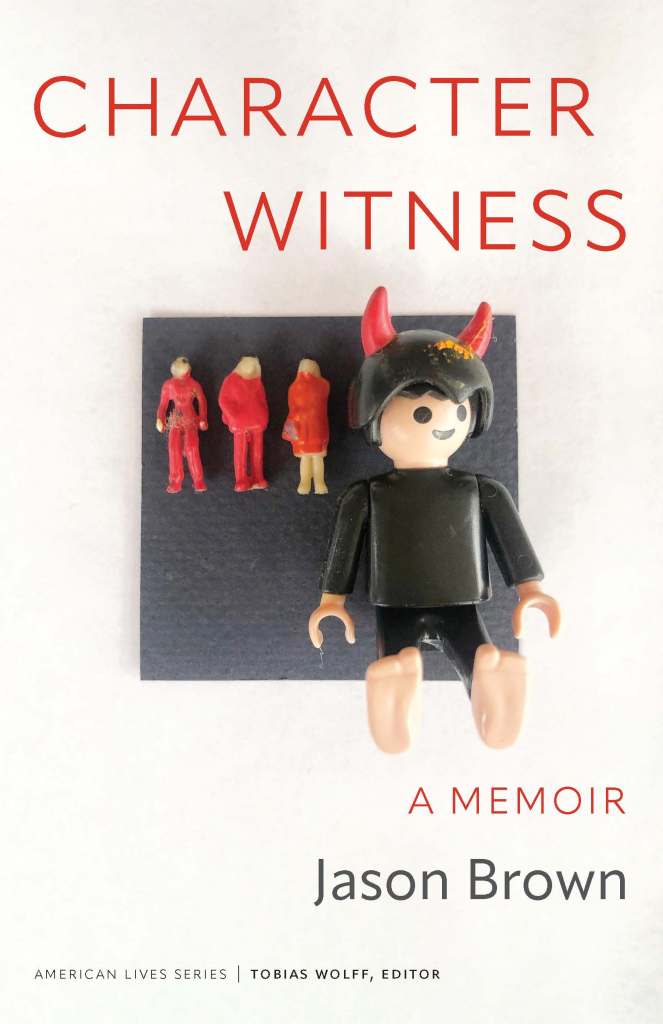

Character Witness

Several months after I came back from the therapy sessions at the Caron Foundation to my job in Tucson, I was sitting in my office trying not to fall asleep when the sixties-era phone on my desk started rattling. Because I had turned the volume all the way down, the ringer sounded like someone shaking a tambourine underwater. The phone was made from green plastic. The metal desk, the floor, and the bookcases were the same green. One dirty window high on the cinder-block wall framed a pigeon that stood looking in at me. This was where I worked, at a university

When I picked up the receiver, a woman’s voice said, “May I speak with Mr. Brown?” This didn’t sound like a student. Students rarely called the office.

The woman on the phone said, “Is Susan Wende your mother?”

In a process I didn’t understand, the institutions my mother owed money to had sold her debt to a guy who drove an eighties Olds with no muffler or hubcaps. He’d come to my house several times asking about her, and each time I’d said I didn’t know whom he was talking about. It was possible that this guy had sold her debt (presumably at a steep discount) to the woman on the phone.

“I am calling from the Pima County Correctional Facility,” the woman said. “Your mother gave your name as a contact person. She is being held in the facility and is scheduled for arraignment at 7:00 p.m.”

“But she’s a grandmother,” I said and fixed my stare on the pigeon in my window. My sister, Liz, had a child. I didn’t.

“She was picked up on a warrant sweep for a class two felony.”

“What did she do?” I didn’t really want to hear the answer.

“I’m afraid I do not have that information,” the woman said and hung up.

According to felonyguide.com, a class two felony carried a sentence of between three and eight years. As far as I could tell, the next step up from a class two was second-degree murder.

There was a knock on my office door, and a head in the shape of the Bell telephone logo appeared behind the frosted glass. A student. The one from Nebraska. I held still and hoped she couldn’t see the outline of my head, though of course she could. I could see the outline of her head, so she could see the outline of my head. Normally, I was happy to meet with students. One of the things I liked about myself was a need to prove to the world that I could be helpful and useful. Teaching fulfilled this need. Today was different, though. After a minute long standoff, her heels tapped to the end of the hall where she opened the door that led to the west side of the building.

I scooted to the east-side door. The Modern Languages Building, designed to thwart protest occupations in response to the student uprisings of the sixties, had no front or central area. Every exit, even the main entrance, felt like a back door. I jumped on my bike, pedaled standing up all the way to my house on Seventeenth Street, and once there drank a glass of lemonade I didn’t enjoy.

From my closet, I removed my only suit, the same one I’d worn to the interview for my current job. I shaved, bathed, and put on the suit and tie. I also pulled on my vintage wingtips, which I hastily cleaned with Windex and toilet paper.

*

My mother, who’d been living an hour south of Tucson with her boyfriend, Daryl, worked for a home-care company that sent her around to the homes of retirees. According to what she later told me, the home-care company had called recently and left a message saying, “You took some stuff from one of the clients.” Later a detective called and left a message: “Lady, we gotta talk.” She declined to return the calls. One of the rings she’d scooped up turned out to be worth $38,000, though her friends at the Cashbox Pawnshop only had given her $5,000. A week after the home-care company and the detective called, she was picked up in an unmarked car, cuffed, and driven to the Pima County Correctional facility, where a woman checked her underwear for weapons and insisted she change into an orange jumpsuit.

They took her picture and typed in her information. Then, according to what my mother later told me, “You go into an area where they offer you horrible sandwiches. It’s called the Pit.” She heard her name on a loudspeaker, but she refused to move. There were cells on the other side of the area with people lying on the floor and banging on bars. A Mexican guy named Pancho sitting next to her said they’d picked him up out of the canal. He’d jumped in to get away. When Pancho asked my mother what she was in for, and she said class two, he whistled and said, “Big time.” She introduced herself to her other immediate neighbors, Pedro, Bobby, and “some skinhead” and told them she was class two. “I was not the worst person on earth,” she later told me. “I didn’t kill anyone!” Then she added, “It does help to know that there are people who are worse off. It makes a person feel better.”

A woman in a pantsuit carrying a file folder approached and looked my mother sternly in the face. “Susan Wende?” the woman asked. “Did you hear me?” she asked again. “You are Susan Wende?”

“I heard you the first time,” my mother snapped. She’d been sitting there for over an hour. She was worn out, she told the pantsuit woman, and she was hungry. She requested a chicken sandwich. Not the garbage they had on offer in the Pit. Would someone bring her a chicken sandwich? In stressful situations, my mother tended to slur, so they might have thought she was drunk at first, but she had quit drinking several years before. Unlike me, she had never attended AA, never gone into the hospital. One day, she simply quit.

Instead of offering my mother a chicken sandwich, the pantsuit woman read off the charges: “Class two felony, trafficking in stolen goods over thirty thousand dollars.” The guys around my mother—the ones making her feel better because she was not as bad off as they were—suddenly perked up.

“Over thirty K. Jesus, lady,” Pedro said. “How the hell’d you do that?”

Ignoring my mother’s new admirers, the pantsuit woman said, “When the judge asks if you understand the charges, you stand up and say, ‘Yes.’ Do you understand what I’m saying to you now?”

“I’m not an idiot,” my mother said.