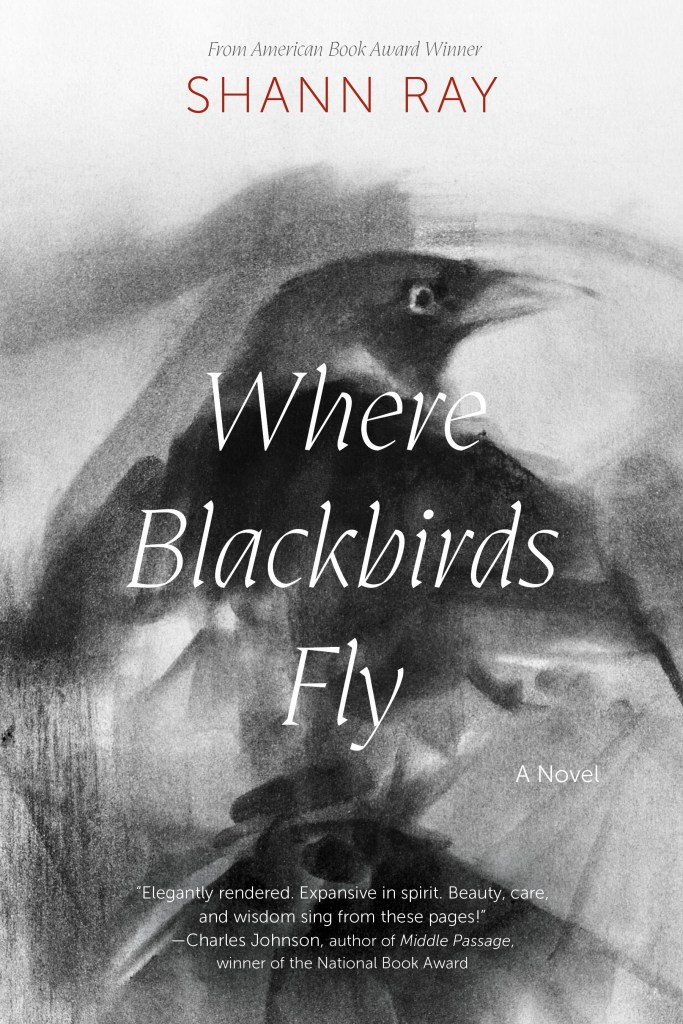

Shann Ray teaches leadership and forgiveness studies at Gonzaga University and poetry at Stanford University. He is the author of the story collection American Masculine, winner of numerous prizes including the American Book Award; the novel American Copper; and the poetry collection Atomic Theory 7. Ray grew up in Alaska and on the Northern Cheyenne Reservation in southeast Montana. Ray’s most recent book Where Blackbirds Fly (Nebraska, 2025) was published in October.

A novel in five novellas, Where Blackbirds Fly offers a prismatic deep dive into the human heart through fierce narratives of intimacy both lovely and heartbreaking. Countering social upheavals, Shann Ray affirms the power of empathy, the wisdom of wilderness, and the felt presence of divine mystery echoed in the recurring appearances of blackbirds, as if etching flight patterns of mercy over the landscapes of human life. John Sender and Samantha Valeria Arrarás seek love in the financial industry, their initial attraction leading to unforeseen perils that will echo in those who enter and exit their lives. The characters of this novel form a compelling cross section of humanity met with revelation, suffering, and possibility. With spare and muscular prose, luminosity, and psychological grace, Ray weaves a tapestry as multihued as America in a vision of love’s transgressive power.

The Simple Truth:

John Sender Believed in Love

Thirty-three. Still single. Driven, overly driven. So much head work, and such solitude, but into his self-doubt, love. Real love. A love he could hardly believe after such drought, but yes, he believed. He’d even gone home to Montana and borrowed his long-dead grandfather’s black Florsheim wingtips from his recently dead grandmother’s bedroom closet, and from her bureau the diamond ring she’d kept through two foreign wars—his mom wanted him to have it—the ring he’d be giving to his bride.

Only he hadn’t much spoken with his bride yet.

He pressed his hands down on the desk, flattening them, staring. Big boned, rough. Late night; everyone gone. Alone again. The day had been difficult, another without tone or hue, loans drawn up, rates secured, moneys meted out. He worked for the world renowned National American Bank, on the seventh floor of its massive headquarters in downtown Seattle. Strange, the bones of a hand, beautiful in their way. His were like his father’s, not afraid of work. White as moonlight and pocked from field work, he thought, with his Czech-German blood, a fraction of it Cheyenne. His hands were also strong like his father’s, but shy with women. His grandfather, a suicide, had been shy with women too. In that echo John always felt uneasy, but he took comfort in how the outline of his fingers against the woodgrain made him think of home.

He had thought he might just stick to horses. They calmed him every bit as much as he calmed them, the kind-spirited ones, the wild ones too, like bolts of lightning he could get a heel into and fight. He missed it, breaking for Dad and the neighbors. That and all the rodeoing he’d done.

Spooked since he could remember, he felt awkward on every date he’d been on, which were few. Tall man: six foot one, wired tight. Bridge of the nose bony as a crowbar, broken on a fence in Flagstaff. Rodeo docs always salty, that one laid him flat on the ground, shoved two metal rods up his nose and got on top of him, then jerked the rods hard. The sound was unnatural, the pain like a landslide in the brain. Straightened things out but left a crude notch. Too tall for saddle broncs, the doc said, but he’d made do.

“Hardnosed,” his dad said when he saw the nose.

“Keeps the women away,” John answered, and they chuckled.

John’s looks were distinctive. Shoulder-length black hair, drawn back, crow-like. Dark blue eyes. Bold features. Big. Just quiet with women, and morose, he thought. His mind tended to focus on things that depressed him. He put his hands through his hair. Easier to see people enter his office hoping to secure a loan, a home. Single or together, they were enthused or subdued. Alone or fused, sometimes disoriented, often good-hearted, isolate or bound like the threading on well-mated nuts and bolts. Secretly, he loved the spectrum of all who hoped for a better life together. He often found the older couples the most savvy. From his own yearning he was undoubtedly biased. Some who married called each other pet names. Others used first names. Still others, silent, said nothing. Engaged, married, or simply together, they don’t know what they have, John thought. When it comes to love, they should realize what they borrow is a person: we borrow them from their family, from their parents. Maybe we borrow them from God. He admitted he hadn’t had much luck with love. But he knew when people thought love dead it surprised you with its presence, and those who commodified love were bankrupt.

Tailored suit and silk tie. Late again, after dark, he needed to finish the paperwork and get home. No cowboy hat, no boots, he felt at odds with himself. A rodeo scholarship and a BA in English from the University of Montana, then three seasons on the professional rodeo circuit and an MBA along with a smattering of additional graduate work in philosophy from Seattle University. He’d been in loans now for a few years, and until he met Samantha everything had seemed caught in a time foreign to him and uglified. Hollow, missing the land and sky. The ranch. Mom and Dad by themselves and him a corporate hired hand, trapped like a pawn in some thoughtless efficiency. He was leery, and still afraid of women. But he wasn’t one to be afraid of darkness. He loved the night—the ocean north of the city not held in city light but illumined by an immensity of stars and the night’s own lan tern. The scent of kelp and mud wash and cold.

And of the women and men who borrowed?

He suffered over them, as he did himself, and his heart went out to them.

John never forgot a face, and those days it was true, life so hectic, so recessed and downhearted, so bubbled with economy, so mealy with anxiety, no one felt compelled to remember, though even slight remembering might have meant help, and remembering well might have meant salvation. People stayed the same or arced upward or fell like meteors from an incomprehensible height. He recalled both the feminist thought leader bell hooks and the Enlightenment philosopher Rousseau: we borrow the land we live on, whispers in the dark, shouts of exultation, the ways we listen or speak, draw near or fade away, the very fruits of the earth and the absolute clarity of unexpected grace. We not only borrow money, he thought, we borrow the unique and versatile manner of our individual and collective lives, and even our common deaths.