Chris Serb is deputy district chief for the Chicago Fire Department. He is also a veteran Chicago freelance writer with almost thirty years of experience as a journalist. Serb’s articles, concentrated in sports and history, have appeared in the Chicago Tribune, Chicago History, Writer’s Digest, Chicago Athlete, and Men’s Fitness. He is the author of War Football: World War I and the Birth of the NFL and Sam’s Boys: The History of Chicago’s Leone Beach and Legendary Lifeguard Sam Leone. His most recent book Eckie: Walter Eckersall and the Rise of Chicago Sports (Nebraska, 2025) was published in October.

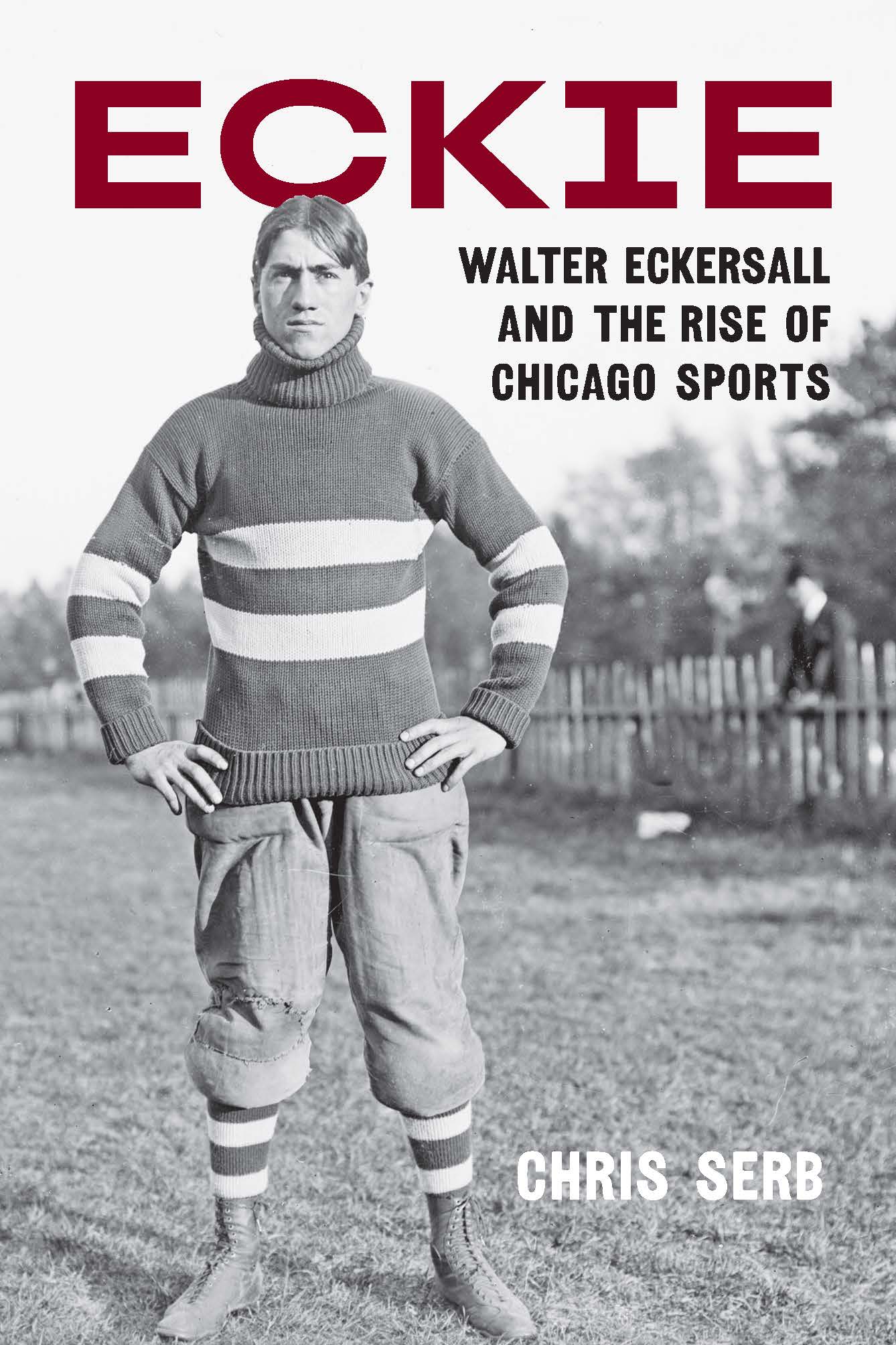

Walter “Eckie” Eckersall was one of the most famous people in Chicago for three decades: He was the city’s first high school athlete superstar when the competitive prep athletics scene was maturing in Illinois, then quarterback of the University of Chicago Maroons, and finally a prominent sports journalist for the Chicago Tribune. While Eckersall was a great player and well-known writer, he had many flaws, some unknown to the public for decades. Chris Serb’s biography sheds new light on Eckersall’s long-forgotten career in the context of Chicago’s burgeoning sports scene.

1. Woodlawn

Located about halfway between downtown Chicago and the city’s border with Indiana, the Woodlawn neighborhood is best known today as the site of the Obama Presidential Center, honoring the legacy of the former U.S. president and longtime Chicagoan. In its not-too-distant past, Woodlawn was a center for community activism and the advancement of civil rights. Before that, Woodlawn was at the center of massive, rapid demographic change, as the neighborhood shifted from 83 percent white to 89 percent Black between 1940 and 1960.

Today’s Woodlawn bears little resemblance to the neighborhood where Walter Eckersall grew up, and even less to the one where his parents settled. Like many Chicagoans of the late nineteenth century, Walter Eckersall Sr. and Minnie Killerlain moved to the area from far away. Walter was born in 1848 in Stalybridge, a textile-manufacturing town in northwest England, and arrived in the United States in the late 1860s. Shortly after his arrival, Walter met Minnie, who was born to Irish immigrants in Vermont in 1850 and moved to Wisconsin as a child. The couple married in Chicago on September 22, 1871, two weeks before the Great Chicago Fire that threw the city into chaos but also spurred tremendous growth.

Woodlawn, where the newlyweds settled, was spared much of this chaos, along with much of the growth. The neighborhood was then part of Hyde Park Township, which was independent from Chicago. Originally settled by Dutch farmers, Woodlawn had between five hundred and a thousand residents scattered through two square miles. That same area has about twenty-five thousand residents today and had more than eighty thousand at its peak.

One of the area’s early attractions was Oak Woods Cemetery, a beautifully landscaped 180-acre burial ground south of Sixty-Seventh Street and east of Cottage Grove Avenue. The now-historic cemetery has become the final resting place for politicians, mob bosses, sports heroes, musicians, and civil rights activists. In 1872 Walter worked as a caretaker at Oak Woods, moving with Minnie into a small cottage on its grounds. During this time, the name “Walter Eckersall” first appeared in the Chicago Tribune, when he took out a classified ad seeking help tending his horses and garden.

The Eckersalls soon moved out of the cemetery and into a small house on Sixty-Fifth Street between Drexel and Maryland Avenues. The house was conveniently down the street from Holy Cross Catholic Church, which opened in 1891. Walter Sr. does not appear to have been formally religious, but Minnie was a lifelong Catholic who raised their children in the faith.

Walter spent his adulthood in working-class occupations. At different times, he worked as a gardener, a laborer, and a construction foreman for a rapid-transit railroad line. Along the way, Walter also pursued a few improbable dreams. In October 1879 he participated in a six-day race-walking tournament in New York City with a grand prize of $5,000, worth more than $150,000 today, along with a host of lesser prizes. (Walter didn’t win anything.) In January 1886 Eckersall was awarded U.S. patent #334,761 for a spring-loaded burglar alarm, though it’s doubtful he made much money from this invention.

Over time, the Eckersalls welcomed three sons and two daughters. Arthur was born in 1876; Elmer in 1877; Etta in 1879; Walter Jr. sometime in the mid-1880s; and Jessie in 1889. Walter Jr.’s birth date is consistently given as June 17, but the year remains unclear. The College Football Hall of Fame lists his birth year as 1886. On his World War I draft registration card, Walter recorded it as 1885. In the 1900 census and on his gravestone, his birth year is given as 1883. And on his marriage and death certificates, Walter’s birth year is listed as 1884. Any year within this narrow range would mesh with the dates of Walter’s major milestones. Most likely, he was born in 1884 or 1885.

Over the course of four short years during Walter Jr.’s childhood, three major events radically transformed his neighborhood. In 1889 Chicago quadrupled in area when it annexed Hyde Park and three other large townships, bringing much-needed services to those areas. In 1892 the University of Chicago, funded by oil baron John D. Rockefeller, opened in the Hyde Park neighborhood, just north of Woodlawn. And in 1893 Jackson Park, on the eastern edge of Woodlawn, hosted the World’s Columbian Exposition, also known as the Chicago World’s Fair, drawing more than twenty-seven million visitors to architect Daniel Burnham’s stunning, though temporary, “White City.”

This period saw a tremendous building boom in Woodlawn, shaping it into a solidly residential neighborhood, without the industrial corridors that developed to the southeast and west. Caught up in this bubble, Walter Sr. made an ambitious financial gamble.