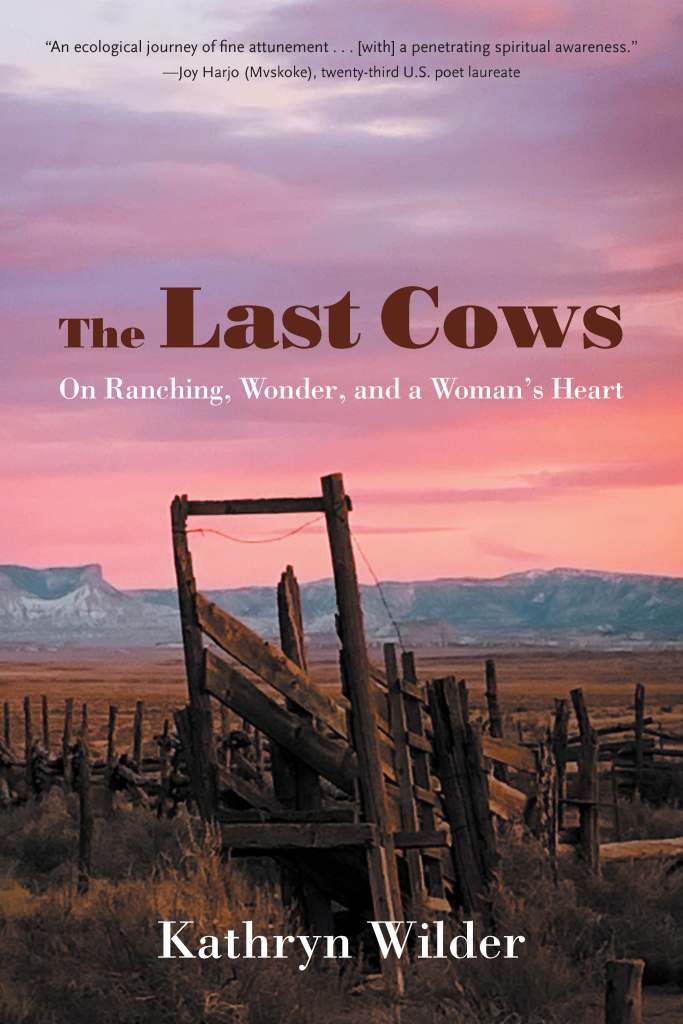

Kathryn Wilder is a writer and rancher in Dolores and Disappointment Valley, Colorado. She is the winner of a 2025 Western Heritage Award and the author of Desert Chrome: Water, a Woman, and Wild Horses in the West, coauthor of Forbidden Talent, with Redwing T. Nez, and editor of Walking the Twilight: Women Writers of the Southwest, volumes 1 and 2. Her latest memoir titled, The Last Cows: On Ranching, Wonder, and a Woman’s Heart (Bison Books, 2025) was published in November.

Told from the unique perspective of a woman, mother, environmentalist, cowboy, and rancher, this work of literary nonfiction conveys the joys, challenges, heartbreaks, and qualms of contemporary ranching in the American West.

On nineteen thousand acres of combined public and private land in southwest Colorado, Kathryn Wilder and her son, with the help of additional family members, run Criollo cattle, a heritage breed that originated in Spain. Smaller by hundreds of pounds than other European breeds, these cows are uniquely adapted to the desert. In The Last Cows Wilder considers whether the integrity of her program—Criollo cattle, holistic management practices, and organically raised, grass-fed-and-finished beef sold through local markets—is enough to support a regenerative relationship between cattle and desert. And as Wilder approaches seventy, she considers how long she can maintain the demanding physical labor and complex schedule that have been part of her life’s work.

Prologue

Tumbling

Endings come.

—David Lavender, “Rancho Los Alamitos” manuscript

Disappointment Valley, Colorado, 2023

As I approach my seventieth birthday, I find myself looking behind me as well as ahead, because a question looms: What will I do with the rest of my life? Followed by: How long can I keep this up? Keep my cows? If the higher They would tell me my off-date, planning might be easier. Instead I am left to figure this out on my own.

In southwestern Colorado, I run a working cattle ranch with my elder son, Ken, and the help of my younger son, Tyler, and Ken’s wife and children. Here the land tumbles out of the San Juan branch of the Rocky Mountains onto the Colorado Plateau, melding with southeastern Utah, northeastern Arizona, and northwestern New Mexico as if no artificial lines separated states, only a movement of geology oblivious to the mapping and geography that created the Four Corners.

The cattle are my day job. Sometimes I live in a cabin above a creek in Disappointment Valley, doing my part of the ranch work while Ken takes care of his part at the headquarters near Dolores, and wherever else he’s needed. The Bureau of Land Management tells us when our cattle can go onto our winter grazing allotment and when they come off—days on a calendar marked, known. The U.S. Forest Service does the same with our summer grazing permit. The days in between these on- and off-dates fill with activities prioritized by urgency—horses ridden, loved, and cared for; cattle checked, doctored, moved, removed; fences checked, fixed, built.

Often I also tumble from the mountains to the desert, loosely following a pattern of seasons. Following our cows. Or following the trails of wildness toward a story. In winter and its shoulder seasons I tend to do this afoot. Summer into fall I’m ahorseback high in the mountains. That’s our ranch—pieces of desert linked to a mountain summer pasture by a watershed like stories linked together by a life.

I grew up with ranches in my background. Rancho Los Alamitos, among the first ranches in my family’s lineage, was built where the Native village of Puvungna once thrived—Puvungna, a sacred place of emergence and gathering for the Tongva people of Southern California. Their creation story begins at a flourishing spring on a hilltop near the Pacific Ocean, where a village blossomed. From there the people spread up and down the coast, inland, and across the water to the southern Channel Islands, living in more than a hundred villages in a vast area called Tovaangar, world. For thousands of years Tongva occupied this region. Then came Spanish exploration and colonization, and thus began for the coastal tribes the years of displacement and death resulting from disease, forced relocation to California missions, enslavement, and starvation.

The Spanish Crown took the land and gave grazing rights, to which it had no right, to patrons such as José Manuel Nieto of the Gaspar de Portolá expedition; Nieto’s provisional “land-use permit” included Puvungna and three hundred thousand surrounding acres and became Rancho Los Nietos. An erasure. The Mexican government replaced the Spanish government in 1822 and distributed Mexican land grants—deeds to the land—and in 1834 Nieto’s descendants received five land grants partitioned from Rancho Los Nietos. From Puvungna. Nieto’s eldest son soon sold his portion, Rancho Los Alamitos. Nearly fifty years later, my great-greatgrandfather, having dabbled with his cousins in buying cattle, sheep, and land since he arrived in California from Maine in 1870, leased Rancho Los Alamitos, and then purchased it in 1881. The spring on the hill is still called Puvungna.

My great-grandfather, raised on and then running Rancho Los Alamitos, acquired another ranch, Rancho el Cojo, in 1913 and the adjoining Rancho Jalama a few years later, both located in Santa Barbara County, where the California coastline elbows from its east-west slant to stretch north at Point Conception. Named by a Spanish explorer sailing past in 1602, La Punta de la Limpia Concepción—Point of Immaculate Conception—already had a Chumash name, Humqaq, the Raven comes. Humqaq has long been considered a stepping-off point by local Chumash, “where our souls leave this earth [for] the afterlife,” says Brian Holguin, Indigenous archaeologist and descendant of the Santa Ynez Band of Chumash Indians. Point Conception, then, is a land of beginnings and endings, as the Cojo turned out to be.

Memories of Rancho el Cojo span my first fifty years: eight miles of California coastline, cattle, horses. I remember foreman Floyd showing my big sister and me how to milk a cow in the old barn that still stands. And my family having breakfast at the long wooden table in the cookhouse, me eating pancakes and peeking at the cowboys seated at the other end of the table. I remember the Appaloosa stallion, Cojo Mapachi, foaled at the Cojo just months after I was born in Berkeley. (Cojo means “lame” in Spanish—the stallion was named for the ranch, not an injury, while Rancho el Cojo was named because of a Chumash chief in the area who walked with a limp.) Cojo Mapachi went on to sire Cojo Rojo, who literally starred under Marlon Brando in the 1966 movie The Appaloosa.

I remember gathering cattle on the Jalama, stopping on a high point beside the ranch foreman, whose hand circled his head as if he were swinging a lariat as he told me that every bit of land we saw was part of the ranches—the north-facing hills of chaparral, deep canyons of poison oak, the ridgelines of coast live oaks, the slope to the sea.

The Cojo had a summer program for family youth, like a ranch internship. I applied, but the ranch-company president said no. I was a girl. And, he said, I could do better than being around cowboys and doing grunt labor. Plus he thought boys and men might feel concerned about bathroom etiquette.

When I told the foreman this, he said, “I don’t care if you’re a man or a woman, as far as I’m concerned you should use the facilities on the other side of the hill.” Meaning, find a tree or a bush and keep out of sight.

Sorting through old papers recently, I found an unsent letter addressed to: To Whom It May Concern (probably me). I had apparently written the letter while under the influence—in it I describe a conversation with a friend in which I tell him about the rejection, my whiskey scrawl full of misspelled words (puek, oficially, sence). I didn’t say that I was in trouble, that I’d hoped working at the Cojo might straighten me out.

“I must create a new plan,” I wrote. “I know what I want to do. What kind of life I want. But how to get what I want . . .”

To my friend I’d said, “I’m going to marry a rich cowboy and own a ranch. Or I’ll find my own ranch and then I can do anything I want. No men around to tell me it’s not my place.”

“Or you could marry a poor cowboy and just be happy,” he said.

And that’s what I did.