Larry C. Skogen is president emeritus of Bismarck State College, an independent historian, and a retired member of the U.S. Air Force. He is the editor of To Educate American Indians: Selected Writings from the National Educational Association’s Department of Indian Education, 1900–1904 and To Educate American Indians: Selected Writings from the National Educational Association’s Department of Indian Education, 1905–1909.

As a graduate student at Central Missouri State University, now University of Central Missouri, I gravitated toward researching something about the unique relationship the United States Government maintained with hundreds of American Indian sovereign nations. Chief Justice John Marshall had, after all, said that the relation of the United States with the Indian nations was “perhaps unlike that of any other two people in existence.” What would be better to study? And as I dived into my interest, I found frequent, almost too frequent, comments about “civilizing Indians.” Writers in and since the 1960s put “civilizing” into quotation marks. Earlier writers left off that punctuation apparently thinking that there was nothing unusual about saying one was civilizing Indians. All this led me to ask the very logical question: what did the white folk mean when they said they were civilizing Indians? I visited Mesa Verde. It looked like the Ancestral Puebloans had a civilization. I grew up in North Dakota where we had tipi rings in our pastures. The Plains Indians obviously had a civilization. In a seminar class I set out to define what was meant by the phrase “civilizing” Indians when used around the turn of the twentieth century.

I then rifled through the card catalog (for young readers, check Wikipedia under Library catalog). I wanted primary sources from the time, not secondary sources by others answering my question. My jottings on a piece of paper led me to the library’s basement—you know the place: flickering fluorescent tube lighting, a low-hanging ceiling, and stack after stack of books left unread for decades. I found encyclopedias, dictionaries, journals, and bound magazine collections from the turn of the twentieth century; plenty of sources for my exploration.

Among the volumes I found dozens of years of Journal of Proceedings and Addresses of the National Educational Association. (NEA dropped the “al” off Education in 1907.) Flipping to the indexes I saw entries for the Department of Indian Education. Turning to the indexed pages I found papers delivered at the NEA’s annual meetings by educators, both administrators and teachers, who worked in the Indian schools. What I learned in reading those papers is that “civilizing” and “educating” Indians were synonymous. Indian schools were “educating” Native students for their role of living in the dominant white society. That included everything from English language acquisition, to wearing “white man’s clothes,” to earning a living as a laborer, to housekeeping—not a tipi or a lodge, but a peaked roof, walled permanent structure. And, of course, Christianizing them. To “civilize” Indians, then, meant to teach them how to live in an English-speaking, Christian, capitalistic society. That is, how to be white men and women.

The papers were rich and illuminating. After reading nine-years-worth of these papers—they were only in the NEA volumes for the years 1900-1909—I knew what civilizing Indians meant. But I now had more questions: Many of the papers were labeled “Abstracts.” Where were the complete papers? Who were the presenters? Most of the names had been lost to history. And, why did the Department of Indian Education only last from 1900-1909? The federal government had been educating Indians much before 1900 and much after 1909. The NEA was founded in 1857 and is still with us today. Why was there an NEA Department of Indian Education for only ten years?

For the next nearly 40 years, that’s right, nearly four decades, I pondered these questions, followed leads on getting full papers, identified Indian school workers who presented at NEA meetings, and began weaving together the tapestry of the ten years of the Department of Indian Education. But I was worried. The papers were so rich in providing a window into Indian schools that I knew someone else, unencumbered by work responsibilities of a military officer and, later, college administrator, would jump at the chance to mine such a rich resource. With each passing decade I was relieved that no one else had. I continued my research.

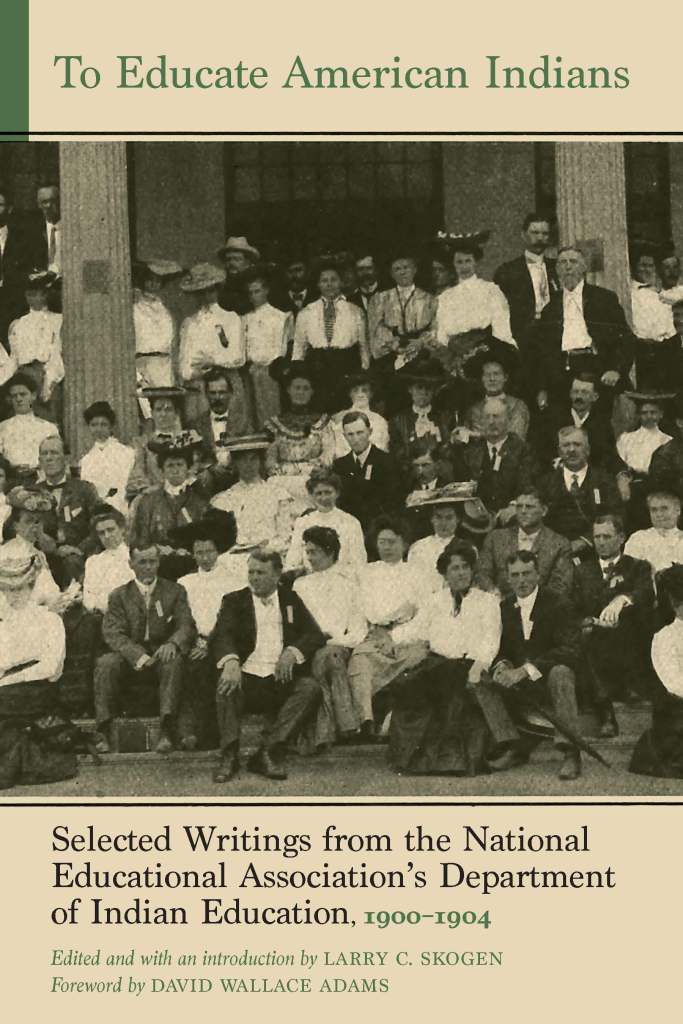

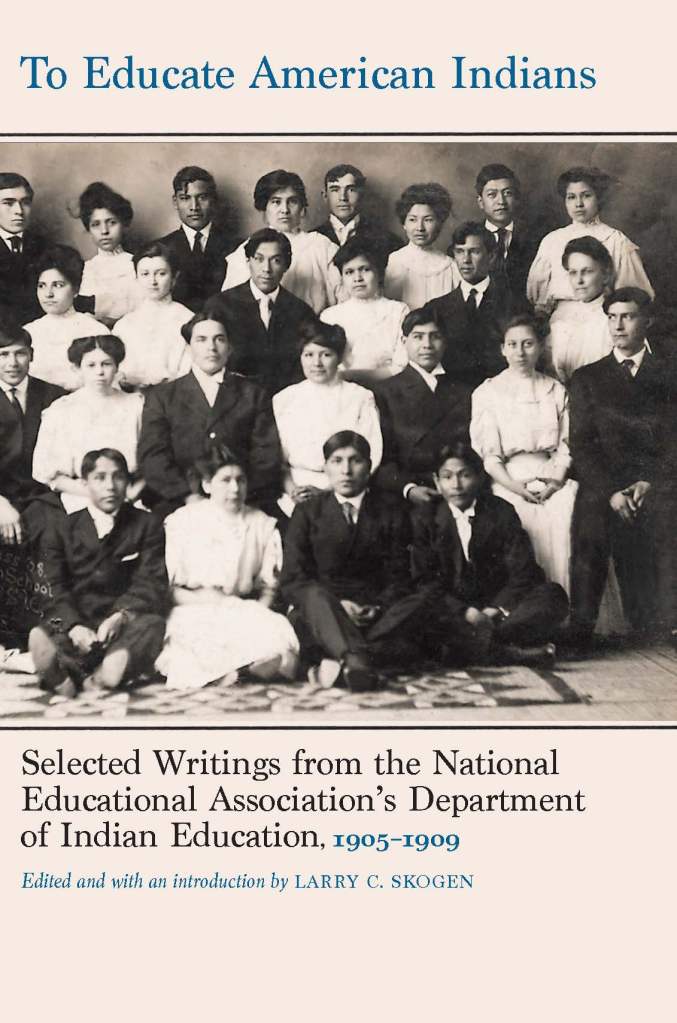

When I retired in 2020, I knew there were things I would not do: play golf, drink coffee with the guys, or join a bridge club. Rather I would work on a volume of papers from the NEA meetings that would highlight the work and attitudes of Indian school workers; introduce those individuals to modern readers; and tell the story of the NEA Department of Indian Education. Sixty-four papers, dozens of individuals identified, and the history of the department turned out to be too massive for a single volume. The good folk at the University of Nebraska Press asked me to divide it in half. Serendipitously, two commissioners of Indian affairs oversaw the entire ten years of the NEA department, except the last two weeks in 1909. The first volume covers 1900-1904, the administration of Commissioner William A. Jones (1897-1904). The second volume comprises 1905-1909, the administration of Commissioner Francis E. Leupp (1905-1909).

My hope is that students of Indian education, federal Indian policy, and Native studies will want to mine these two volumes. They will find illuminated the attitudes of Indian school workers toward their Native students; the realization that those things about the Indian boarding school experience we condemn today were equally criticized by Indian school workers then; and, the strongest condemnation of this “civilization” process I’ve ever read: “To let these [cultural traits] perish is a crime for which our codes have no penalty and our lexicon no name. It is the slaughter of the soul of a people.” Yes, that was said in 1908. There is much to learn about Indian boarding schools, federal policies regarding Indian education, and this nation’s “civilizing” of our Indigenous citizens. The selected papers of the Department of Indian Education is a good place to start.