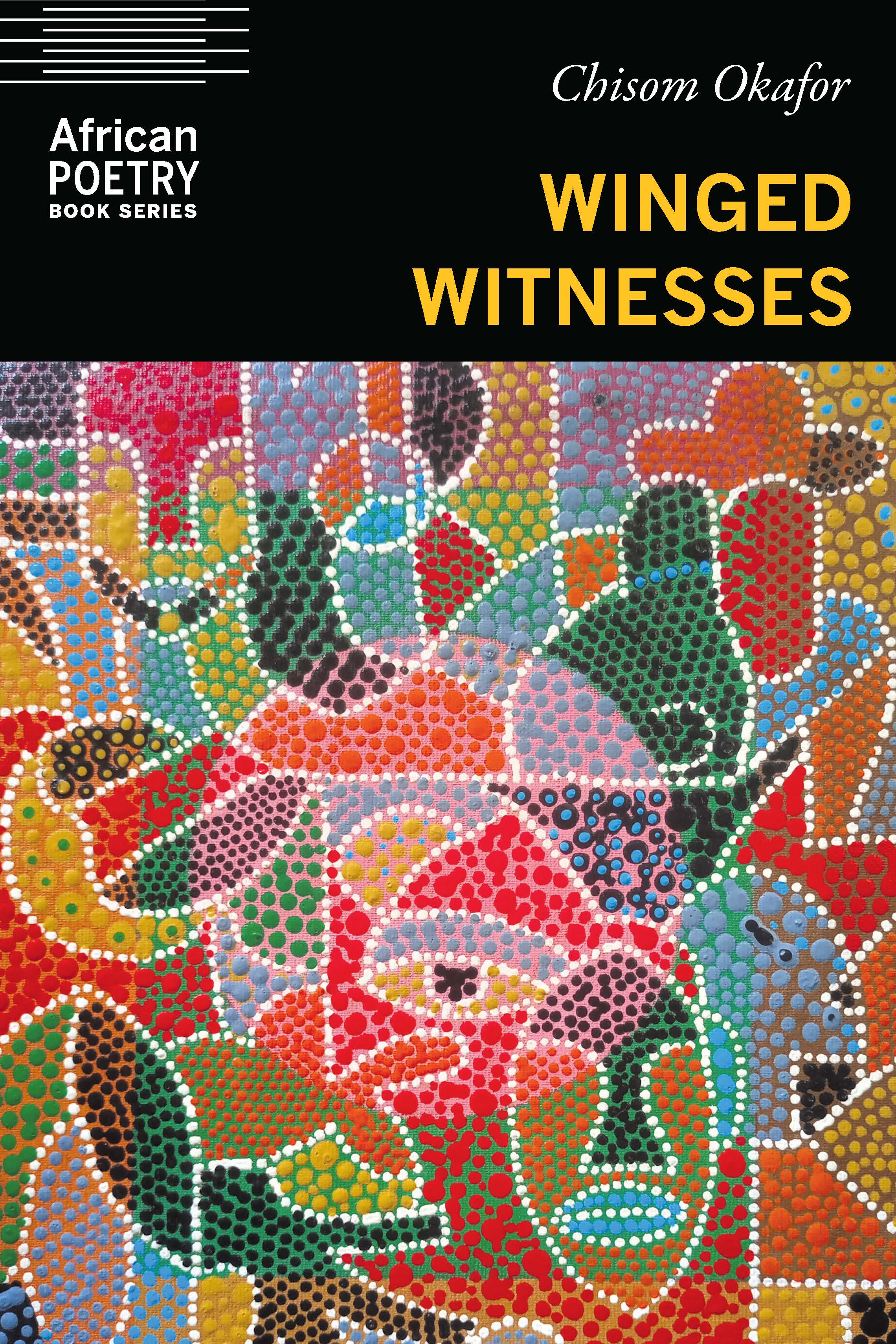

Chisom Okafor is a Nigerian poet and clinical nutritionist. His poems have appeared in Beloit Poetry Journal, Prairie Schooner, the Raven Review, the Hellebore, North Dakota Quarterly, Salt Hill, Sand Journal, the Account, Rattle, and elsewhere. His most recent book Winged Witnesses (Nebraska, 2025) was published in December.

Chisom Okafor offers poems that are intense, gripping, and perfect for pondering. The poems are a force field for questions: When we embody life through disabled, chronically ill, and neurodivergent body-minds, how do we grapple with love, time, and consciousness?

These poems are alive to history and highlight the way poetry’s memorial practices animate the raw intimacy between the seen and unseen. There is trauma in these poems, but also light and salvation, and everything that comes between.

Animalcules

What first greets anyone who enters this room

is not the medication, not my drooping eyes,

tarrying undecided between recovery and relapse,

but the old bible left on the stool, just beside my bed

where my father’s hand can swiftly reach it.

At midnight, he flips it open and for a long while

stares at the vignette of the Last Supper

on the first page, as if to crawl inside it

and save Jesus from imminent death

then I hear him recite his favorite bible verse

into his palms, supple with anointing oil,

his mouth dense with the book of Isaiah:

Ma ndi n’ele anya Chineke . . . ga-agbanwe ike ha

Ha ga-agba ósó, ike agaghi agwukwa ha

Ha ga-eje ije, ghara ida mba.

But those who wait for God . . . will renew their strength

They will run, and not be weary

They will walk, and not faint.

Afterward, he keeps vigil, his breaths

steady and drawn against the long moan

of the night like a snake’s hiss. His head

is bowed in a catnap, the way St. Francis

must have appeared on the night

of his first missionary trip, bent with exhaustion.

I fall into a trance and there is an army of bacteria

invading my body’s defenses

dressed in deceitful clothing.

They populate the islets of Langerhans

slice through the sphincter of Oddi

infiltrate the Bowman’s capsule

graze on the walls of the Cowper’s gland

and curl round the loop of Henle

while I’m left muttering every one of god’s names

I ever committed to memory

Rapha. Jaireh. Sabaoth

which is my most preferred name for god

Sabaoth: a platoon of insurgents

charioting into my body,

an invasion of an already-invaded land.

But it’s hard to think about horses when

my father’s voice stubbornly tickles my ears

and his prayers keep falling like many

little animals on my infected chest

as I pretend to fall asleep.

Petrichor

You invite me to the slow violence of your body.

I could feel your delight, like rain

turbaned around the circumference

of a rain-bathing child’s head,

and just after the entrance

I make a detour, convulsing

with hunger for the things

I have lost from my previous life.

Within the waves of your body

and up to the points where

the spiraling light is first refracted

before it turns impenetrable

like a passage through

a prism of glass

opaque and translucent in equal measure,

I search for a song

that used to be mine

but which has now become a sailor’s talisman lost at sea

and believed to be nestled

between membranes and tissues of your body.

There is a story hidden within the story

of my departure from home.

Peep through, and you’ll see my father

clutching a chest already squeezed out

with angina pains, or an uncle

dying slowly from an affliction

that has refused to grow old.

It is hard to die, he says to me.

It is life we should be afraid of, not death.

Lay me on the shelter of this new knowingness.

Sing me a buffet of vocables,

an à la carte of phosphenes until I’m satiated.

It’s seven years after my drifting

apart, but I still fail at the subtle art

of forging recovery psalms.

Tell me, how do you forgive what has refused

to stop punishing you?

How do you return to the sweet agonies of a previous life?