Steve Bialostok is a professor of anthropology at the University of Wyoming. He is the coeditor of Education and the Risk Society: Theories, Discourse, and Risk Identities in Education Contexts. His most recent book Playing to the End: Elder Black Men, Placemaking, and Dominoes in Denver (Nebraska, 2026) was published in January.

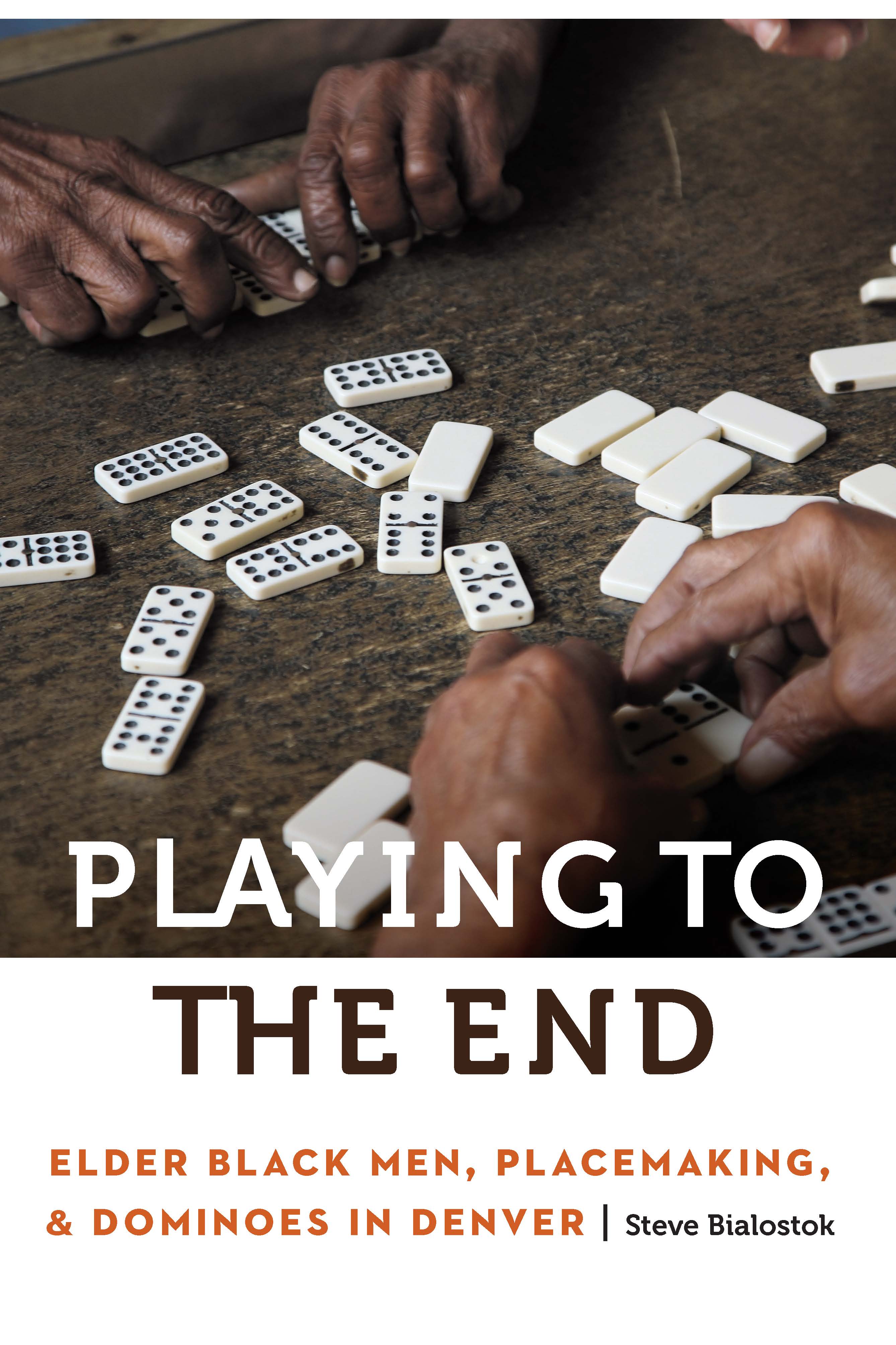

In Playing to the End, Steve Bialostok immerses readers in the vibrant world of the card room at Denver’s Hiawatha Davis Jr. Recreation Center, where a group of older Black men gather to play dominoes, exchange playful banter known as “talking shit,” and cultivate a space of belonging. More than just a game, their gatherings are acts of Black placemaking—resisting cultural erasure, gentrification, and societal marginalization while fostering joy, resilience, and community.

Through five years of ethnographic study, Bialostok reveals how these men transform the card room into a sanctuary of identity and defiance, where humor and camaraderie become tools of self-determination. As they navigate the pressures of a changing neighborhood, their interactions affirm the power of play, talk, and collective memory in sustaining Black spaces. Playing to the End is a compelling testament to the significance of these gatherings and the ongoing struggle for autonomy, cultural affirmation, and social connection in an inequitable world.

Beginnings

“Give us fifteen!” Mr. Buford calls out his score loudly, having added the numbers of white domino pips on the exposed end of a line. Mr. Buford, a feisty and loveably cantankerous octogenarian, rarely misses a domino game.

“Partner, you play so pretty,” Mr. Hall says. Domino plays, as in other sports, can be praised for their beauty.

“You know what?” D-Ray’s throaty tone always sounds agitated. “There’s a whole lot of fives and shit out here.”

“Huh? . . . I don’t see no five.” Mr. Taylor feigns confusion. His constant quips keep the others amused.

“Quit talkin’ the game!” says Mr. Hall, normally of gravelly voice and laconic manner, playfully admonishing the men’s loud, showy, and “out-of-control” talk. His comment is intentionally ironic since boisterous talk is the point.

“You ain’t shit!” says D-Ray, who is filled with willful bravado but intimidates no one. It’s only a matter of time before his momentary scowl is replaced by a thick smoker’s laugh. As Mr. Taylor once described it, the “shit talk” that accompanies the game of dominoes is “a whole lot of nothing”—but they wouldn’t have it any other way.

I learned to play dominoes with Mr. Buford, Mr. Hall, Mr. Taylor, Mr. Carr, and D-Ray—who, unlike most of the elderly men in the group, declined the honorific. These retired Black men, ranging from their mid-seventies to ninety, taught me the game with patience and care, even if I never fully caught on.

How I Discovered Dominoes

In 2015 I was introduced to the Hiawatha Davis Jr. Recreation Center, where I began participating twice a week in a Silver Sneakers exercise program and took a ceramics class every Wednesday. Like me, most of the participants were seniors, many of whom lived in Denver’s Northeast Park Hill neighborhood. Each time I attended, I passed the card room and sometimes stopped to listen in. The energetic banter among the men inside gradually captivated my attention and caused me to slow my pace. Eventually, I mustered the courage to enter, offering a nod and a smile each time I settled at an empty table to watch the spirited card game and merciless teasing that accompanied it. One day, after many visits, Samuel, one of the four Black octogenarians playing that day, approached me after his game ended. He stood up, pivoted with his walker, and—after I naively failed to introduce myself, asked, “Are you undercover?” “No,” I responded with a slightly awkward laugh, “I’m just interested in your game. What are you playing?” “Pinochle,” he answered.

This brief exchange helped break the ice. Samuel silently pushed his walker back to the card table and introduced me to the men sitting there. From that day forward, whenever I entered the card room, Samuel and I exchanged nods. The regular pinochle players followed his lead.

Then one afternoon, I met Grover. Before entering, he momentarily stood just inside the doorway, with a grin on his face and an Oakland Raiders baseball cap worn backward. A youngster by comparison—he was only in his fifties—Grover drew attention by flicking the room lights and boisterously announcing, “The champ is here!” I would later learn that this performance was typical for Grover. He came over and asked what I was doing. I told him I was interested in the game, but especially in how the men spoke to each other. Grover gave me a puzzled but curious look. After I provided a couple of examples of the banter I’d overheard, he grinned and said, “Yeah, that is interesting. I never thought about it that way.” Grover then helpfully volunteered one of the most important rules of card room banter: “You don’t talk about your wife or your family.” He led me to the pinochle table and began explaining the game as the men played. “It’s easy,” Grover reassured me, perhaps noticing my eyes widen with fear as he talked. I sat at the table for several weeks, usually with Grover by my side, socializing with the men and trying to figure out the game.

Serendipity brought me to dominoes. One afternoon, I happened to stay later than usual and witnessed a changing of the guards around 4:00 p.m.The pinochle players stood up, gathered their belongings, and put the cards away in the closet. Gradually, a new group of elderly men walked in and settled at several tables. I watched my first domino game, which featured even more spirited banter than cards. Later that week, during a Silver Sneakers luncheon, I mentioned my brief observation to my exercise “neighbor.” As luck would have it, she lived next door to Bobby Cummings, who had organized the first dominoes game in the mid-1960s and attended every night. She offered to contact him on my behalf.

The following week in the card room, I heard a lean and spry octogenarian say in a ringing voice to the group of men he sat with, “Some guy is supposed to come here and talk to me about the tournament. I don’t know what happened to him.” I raised my hand like a shy elementary school student, hesitantly vying for a turn. “I think that’s me,” I said. We moved to a tiny and cluttered office next to the card room. A former medical technician, Mr. Cummings had worked at a local hospital in the 1960s where he started as the only Black employee. He recalled the days at the center when “we used to play in front,” referring to the early years when the recreation center was known as Skyland.

Mr. Cummings shared a wealth of information about the domino tournament and its previous management, the origin of the domino sets in the room, and his purchase of new plastic tables to withstand the domino slamming. He also mentioned that the National Basketball Association star Chauncey Billups had grown up at the center and still came around. Mr. Cummings detailed the lobbying and planning that went into the center’s massive renovation in 2000, including his efforts to ensure they set aside a room for cards, chess, and dominoes. When I

expressed my admiration for the men’s unwavering commitment to playing five times a week, he told me that the men drove over every afternoon to play, with most staying for about four hours. “Do their wives care?” I asked. “I don’t know,” he responded with a wry smile. “But they play!”