The one hundredth Tour de France started Saturday,

The one hundredth Tour de France started Saturday,

June 29. Each summer for the past fifteen or so years, I anticipate the guilty

pleasure of sitting on the couch in a climate-controlled house—watching as the

Tour riders gut it out in a range of weather conditions on their epic journey

to Paris. The three-week, twenty-one-stage race packs in a surprising amount of

human drama as the ever-shifting alliances and tactics play themselves out

against the backdrop of long-standing rivalries.

The riders endure desperate ascents, thrilling and

terrifying descents, daring breakaways, heartbreaking crashes, injuries, and

sickness. They do this within reach of hundreds of thousands of fans who line

the course—mostly adoring, often drunk, and at times dangerously hapless. The

race finally ends on the cobblestones of Paris with a mad sprint for the final-stage

victory.

When the Tour riders cross the finish line in

mid-July, they will have covered 3,479

kilometers, averaging something like one

hundred miles per day for three weeks, much of it in the

mountains, with just two rest days. Their will to undergo the necessary

suffering, with or without doping, never ceases to amaze me. The glory of a Tour

rider’s triumph, however, is often eclipsed

by the shadow of doping. Although doping has possibly existed (in more

rudimentary forms) as long as racing itself, its modern pervasiveness is frustrating

and confounding. With darkness threatening to overshadow cycling’s most iconic

race, I return to a book that I love because it celebrates the bike as a thing

of beauty and a renewable source of joy.

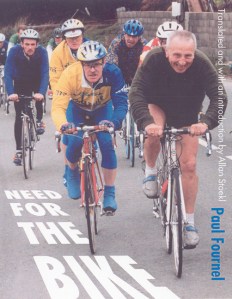

The book is Frenchman Paul Fournel’s compact and understated

gem Need for the Bike, translated and introduced by Allan Stoekl and published

in 2003. Fournel has had a career in publishing and is a longtime member of the

Oulipo literary collective. His wonderful writing and his deep and abiding love

of the bike are both antidotes to despair. I cannot resist quoting from Fournel,

but you will soon understand why:

“The

bike is a brilliant device that permits a seated person by the force of just

his or her own muscles to go twice as far and twice as fast as a person on

foot. Thanks to the bike, there is a faster man. The bike is itself a form of

doping. Which doesn’t simplify things. It’s the tool of natural speed; it’s the

shortest path to the doubling of yourself. Twice as fast, two times less tired,

twice as much wind in your face. It’s all right always to want more.”

Fournel’s drug of choice is the bike. And it seems

he was a very young addict. In the chapter titled “Miracle,” he describes the

joy of first liftoff: “The bike always

starts with a miracle. For days you tremble, you hesitate; you tell yourself

that you’ll never get rid of that hand guiding you, under the seat. . . . And

then one morning I no longer heard the sound of someone running behind me, the

sound of rhythmic breathing at my back. The miracle had taken place. I was

riding. . . . I’ve never gotten over this miracle.”

Fournel says that he discovered reading and riding

within a few months of each other and at the age of five had discovered both

his work and his leisure. His Need for

the Bike is a magical marriage of both passions. His series of vignettes—ranging

from one paragraph to four pages—forms an extended meditation on cycling.

Grouped into five sections, “The Violent Bike,” “Bike Desire,” “Need for Air,” “Pedaling

Within,” and “Spinning Circles,” Fournel spins stories about cycling with others

and cycling alone. He writes about bikers’ tans, bikers’ legs, haute couture, watching

the Tour, wind, sounds, landscapes, doping, the need for hunger, the need for

exhaustion, and the need for rest. He speculates about being a racer and a bike

mechanic and about what animals think when a bicycle passes.

In Stoekl’s introduction he compares the rich bicycle

lexicon and lingo of the French to the Eskimos’ vocabulary for snow. As he explains,

“Fournel presents a world, a very

personal one, whose axis is the bicycle. It’s a world of communication, of

connection, where all people and things pass by way of the bike. . . . Cycling

is not simply a series of techniques but rather a descriptive

universe—colorful, lyrical, peopled with gods and demons—a coherent universe in

which one lives, or wants to live, and from which, on occasion, one senses a

bitter exile.”

My husband, a former amateur road racer, also has a

serious bike habit. He now prefers to ride off-road or grind out very long rides

on gravel back roads. Perhaps unwisely, and although I have my excuses, I’ve mostly

replaced cycling with running for now. Nevertheless, Need for the Bike takes

me back to the pleasures of cycling, some of which overlap with the pleasures

of running.

Our four-year-old daughter is now learning the ways

of the bike as we accompany her around the neighborhood while she rides her bike

with training wheels. Her mix of fear and excitement when descending a hill and

her efforts ascending a “really, really, really”

big hill return us to cycling’s essential challenges and satisfactions. One day,

sooner than I’m ready, she’s going to leave her training wheels behind as she finds

new equilibrium and discovers the joys of flight. In the meantime, she’s content

with her training wheels—as well as her rides in the Burley pulled by my

husband, making up songs as she goes.

Although Fournel focuses attention on “The Violent

Bike” and the variety of accidents he has endured, he seems at heart to be a

gentle soul who continually returns to the bike for its restorative powers:

“I’ve

ridden with stitches, with bandages, with scabs. I’ve ridden out of focus,

undefined, until the luminous clarity of being in shape returned. I’ve never

lacked the desire. It’s been a sunny and twisting road, from the childish

desire to own a bike to the need to ride it. Up to now every time I’ve

questioned myself, I’ve just jumped back on my lovely bike and gone for a

spin.”

I can’t resist closing with a final excerpt from

Fournel—that merges publishing and the Tour—as he heads for vacation on his

bike:

“My ideal

vacation starts at the beginning of July. Work in Paris is slowing down. The

last cocktails have been served. Summer books have been out for a number of weeks,

the fall books are at the printer, and the Tour de France is still in the

first, flat stages. The need for silence has become crucial. It’s time to get

on the road. . . . . Four days of

perfect peace without saying anything other than what’s dictated by the bike’s

refrains, four days of hard-core silence to purge me of the torrent of words that

constitute my everyday work, four days of physical violence to get revenge on

my armchair. There’s nobody on these French back roads and the transformation

of Homo intellectus into Homo bicycletus takes place in private.

-Tish