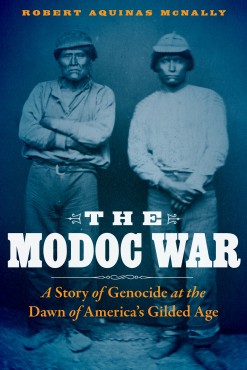

Robert Aquinas McNally is the author of The Modoc War: A Story of Genocide at the Dawn of America’s Gilded Age (Bison Books, 2017), which won a 2018 Commonwealth Club of California gold medal for the year’s best book on California.

California’s Genocide Steps into the Light

In the two years since The Modoc War: A Story of Genocide at the Dawn of America’s Gilded Age came off the press, something significant—and hopeful—has been shifting in the public mind. It’s gotten to the point where California’s long-hidden genocide is hardly news anymore.

The first readings and presentations I gave after my book appeared emphasized the state’s extermination campaigns against Native peoples in the late 19th century. At the time, few people, even avid readers, knew about the genocide. My audiences—mostly folks as white as I am—were startled and disturbed, sometimes even resisting the notion that such a home-grown atrocity could be real. Now, the presentation elicits more of an “Oh, yeah, we’ve heard about that.” That’s a big change in only two years.

Denial is the last stage of genocide, and, apart from a number of scholars who intimated that the destruction of California’s Indigenous peoples was too extensive to be accidental, the genocide was long kept under wraps. The first major unveiling came in 2012, when the University of Nebraska Press published Brendan Lindsay’s Murder State. This book wove various scholarly threads into whole historical cloth and named the California genocide for what it was. Importantly, Lindsay wrestled with how a democracy orchestrated mass murder, warning that democratic institutions are no guarantee against mass atrocity.

Denial is the last stage of genocide, and, apart from a number of scholars who intimated that the destruction of California’s Indigenous peoples was too extensive to be accidental, the genocide was long kept under wraps. The first major unveiling came in 2012, when the University of Nebraska Press published Brendan Lindsay’s Murder State. This book wove various scholarly threads into whole historical cloth and named the California genocide for what it was. Importantly, Lindsay wrestled with how a democracy orchestrated mass murder, warning that democratic institutions are no guarantee against mass atrocity.

That perspective was buttressed in 2016 by Benjamin Madley’s An American Genocide. This book proceeds year by year by year from 1846 to 1873, detailing laws passed to dehumanize Indians, murderous actions taken in more than 1,100 militia raids and some 115 military campaigns, and reservations starved out. The result was near annihilation on a scale unequaled anywhere else in the United States.

Since then, denial has further eroded, word keeps getting out, and more and more Californians outside tribal communities are owning up to what happened. That trend became obvious in June of this year, when Governor Gavin Newsom admitted to and apologized for the genocide before a gathering of Native leaders. And just as I was drafting this post, the California city of Eureka deeded over Tuluwat Island to the Wiyot tribe, which was nearly wiped out in an 1860 massacre at that very site. Returning the land constituted a step toward restorative justice the Wiyots had been advocating since 1970.

Historians like Lindsay and Madley and writers like myself want to believe that our books have helped bend the moral arc of the universe in the direction that prompted Newsom’s apology and Eureka’s repatriation. I’m sure they helped, at least a little. But rising awareness of the genocide is due far more to the persistence and presence of California’s Native citizens.

While promoting The Modoc War, I did several bookstore readings with Greg Sarris, a novelist and professor who chairs the Federated Indians of Graton Rancheria in Rohnert Park, California. Every enrolled member, Greg told me, is descended from just 14 Coast Miwok and Southern Pomo survivors. Yet today the population of the Federated Indians numbers 1,454.

In the end, as the Federated Indians of Graton Rancheria exemplify, the genocide failed. Today there are 109 federally recognized tribes in California, and another 78 are in the process of winning or regaining recognition. In addition, Native people from other parts of the country have moved to California. As a result, the 2010 census identified more than 723,000 residents as Native American or Native Alaskan, giving California the largest Indigenous population of any American state or territory.

Those swelling numbers have laid the foundation for a Native literary renaissance. The past two years have seen the publication of the acclaimed novel There There by Oakland-born Tommy Orange (Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes of Oklahoma) and the Twitter-inflected, award-winning Nature Poem by Tommy Pico (Viejas Band of Kumeyaay Indians). In addition, poet Natalie Diaz (Gila River Indian Community) was named the recipient of a $650,000 MacArther Foundation genius grant.

On the political side, Native power has been growing since activists occupied Alcatraz Island in 1969. That protest set the stage for a Native-led outcry against the effort to put Junípero Serra, founder of California’s violent mission system, on the ecclesiastical path to Catholic sainthood in the 1980s. Although Pope Francis made Serra a saint anyway in 2015, the well-publicized effort against canonization resulted in a 2017 state law requiring development of a model Native American studies curriculum for high school students.

As Governor Newsom offered his apology for the California genocide in June, he was flanked by James C. Ramos (Serrano/Cahuilla), the first California Indian elected to the state assembly, who opened the meeting with a blessing and a traditional bird song. And now the California Native Heritage Commission has unveiled the new “Protect Native Culture” license plate, which will raise funds to protect and preserve Indigenous cultural sites in the state.

The executive order accompanying Newsom’s June apology includes a mandate to the Governor’s Tribal Advisor Christina Snider (Dry Creek Rancheria of Pomo Indians) to establish a California Truth and Healing Council fashioned after the South African and Canadian Truth and Reconciliation Commissions. Made up primarily of tribal representatives, the council will produce an annual report beginning January 1, 2020, and issue a summary of findings in 2025.

California’s Truth and Healing Council will hardly be the last word on the genocide’s fraught, dark, and longstanding legacy. But, like Governor Newsom’s apology, the rise of California’s Native artists, and the return of Tuluwat, it is a first step from the darkness into the light, the initial chapter in a new history of hope written by California’s Native people themselves.