David Kamper is a professor of American Indian studies, associate director and cofounder of the Center for Skateboarding, Action Sports, and Social Change, and cofounder of Surf/Skate Studies Collaborative at San Diego State University. His most recent book is Rezballers and Skate Elders: Joyful Futures in Indian Country. He is also the author of The Work of Sovereignty: Tribal Labor Relations and Self-Determination at the Navajo Nation and coeditor of Waves of Belonging: Indigeneity, Race, and Gender in the Surfing Lineup.

Ethnographer and American Indian studies scholar David Kamper examines how Indigenous youth and adults are making basketball and skateboarding meaningful to their communities by sustaining the transmission of intergenerational knowledge and combatting intergenerational trauma. Kamper looks at how the events and tournaments built around rezball are similar to powwows in how they bring people together across localized communities and generations and he coins the phrase “skate elders” for those who use the social nature of skateboarding to build community and mentorships.

Through a broad picture of North America, Kamper demonstrates how Native peoples have long indigenized cultural practices and material culture to assert Native sovereignty, creating joy and hope in the process. In Rezballers and Skate Elders Kamper considers how Native expressions of basketball and skateboarding show continuities with the historical transformation of practices that originated outside Indian Country to make them meaningful in Native life.

Introduction

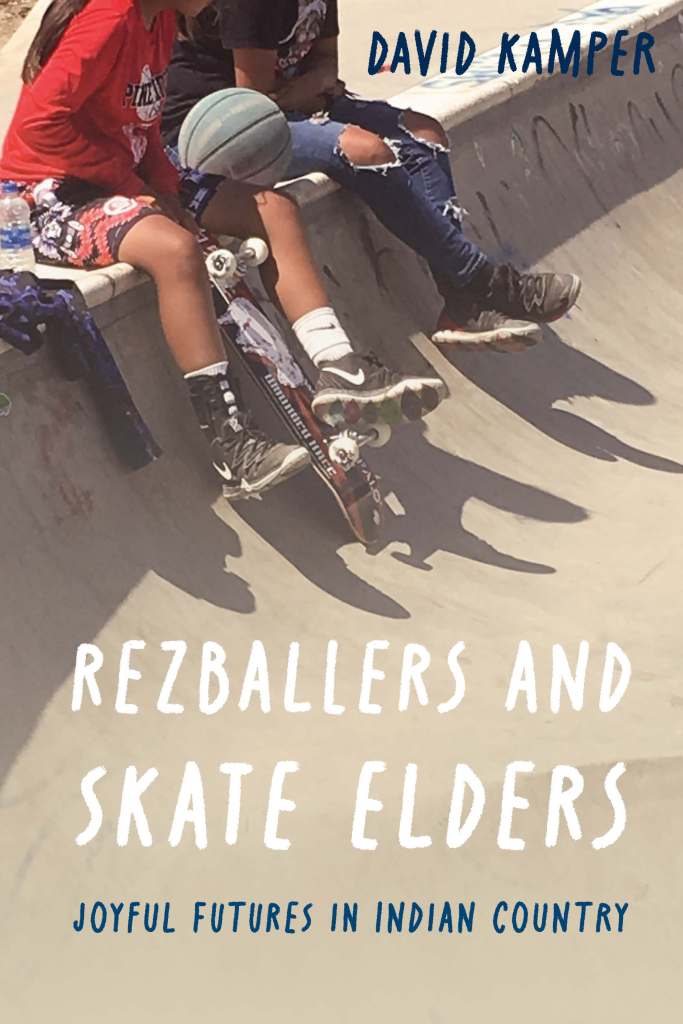

It was a gorgeous early August day in 2019, warm, bright, and colorful. Three hundred and sixty degrees around me was festive activity, smiles, cheers, and happiness. I was standing on the edge of the concrete bowl of the WK 4-Directions Skatepark in the town of Pine Ridge on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation—which is sandwiched between what the U.S. settler state labels as the Badlands National Park and the state of Nebraska. The skatepark was built with the help of the Native-owned Wounded Knee Skateboards company and two nonprofits, the Stronghold Society and Montana Pool Service. The WK 4-Directions Skatepark is part of a larger outdoor recreational complex in the heart of the reservation. As I stood at the park on this beautiful day in August: to the east of me was a softball game being played with the leisurely intensity that can only be found in softball; to the south kids were throwing a football around on an open field, no organized game, just running routes for fun; to the west was a pickup basketball game at which one teenager just arrived, riding bareback on his horse, to join the game despite wearing jeans; and to the north was the tail end of a community parade consisting of elders and tribal council representatives smiling, waving, and throwing candy from “floats” being pulled on trailers behind large pickup trucks or from the backseat of convertibles. Behind these floats were several powwow dancers marching or dancing in the parade wearing full regalia. This particular day was the annual Lakota Wicipi, a thoroughly community-based multiday event that combines powwow, rodeo, sports, and the promotion of Lakota culture in all forms and varieties. There was much joy in the air.

The Lakota Reservation at Pine Ridge is a singularity in the public imagination of Indian Country. It often stands in for all the Indigenous communities in North America, as a synecdoche or prototype for American Indian reservations—at least from the perspective of non-Natives. With good reason though, given the number of historically significant events that took place on this land. Events that are keenly representative of different eras of Indigenous resistance to and suffering from North American settler colonialism. Yet at the same time this overrepresentation of Pine Ridge speaks to particular settler narratives of Indians being either barbaric savages that needed subduing or noble warriors who fought hard to maintain traditional lifeways. Either way, these tropes of “primitivism” have always marginalized Indigenous communities, making them seem to be out of time or irrelevant to the modern, civilized world. The overrepresentation and oversimplification of Lakota society, and Indian Country as a whole, as merely synonymous does harm to all of Indian Country by distilling the diversity of American Indian history, culture, and communities to a few simple tropes of barbarism. More recently, an overemphasis on Pine Ridge and the challenge it is to live on this reservation is frequently employed as a metaphor to highlight the tragedy and suffering of American Indians. Since the mid-twentieth century Pine Ridge has frequently been used as either a cautionary tale of poverty, addiction, and trauma or a halfhearted critique of (or semi-admission of blame for) the history of U.S. white supremacy and federal Indian policy (see the Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee book and film, Thunderheart, and countless documentaries, books, and academic articles). This overemphasis on Pine Ridge is deployed to code Indigenous spaces as devastated, depraved, and depressed. Certainly, these terms have some utility in describing part of Indian Country, but all too often damage-centered narratives obscure and override the true joy, happiness, and vibrancy that pulses through Indigenous communities (Tuck and Yang 2014).

This book attempts to highlight that joy, happiness, and vibrancy (without ignoring the pain and intergenerational trauma) of Native American communities by focusing on just two of the many things Native people do for fun: play basketball and skateboard. As an integral part of nearly all localized communities, sports sustain communal and individual life by building solidarity, promoting physical and mental health, and socializing youth (in both collaboratively beneficial and hegemonically problematic ways). On a regional and global scale, professional and Olympic sports play a major role in contemporary consumer capitalism, producing massive revenues from event-based competition and entertainment and providing far-reaching venues for the marketing of ancillary products and services (Carrington and McDonald 2009; Zirin 2009, 2016; Boykoff 2023). Despite the increasing global-facing articulation of professional sports, local community-based sports are still a significant part of communities all over the world, though this tends to be more in the realm of leisure, not professionalization.

American Indian communities are no exception when it comes to communal expression of sport. Sport has been a key part of Indigenous life well before and long after contact with European settlers. American Indian communities have always combined the physical with the spiritual to maintain a balance between mental, emotional, and corporeal health. Kinesthetic ability and endurance are key parts of the ceremonial-, leisure-, and sustenance-based activities of Indigenous peoples. Arguably, this holistic approach to health is the reason why what is now called “sport” has been so prevalent in American Indian communities. Yet I also take caution not to romanticize Native American participation in sports and physical activity. Historically discourses of Indians as “natural athletes” have been used to sustain settler colonial agendas pitting primitive versus civilized, ancient (and vanished) versus modern (see Deloria 2004). This book illustrates that there is much to suggest that contemporary Native folks participate in and conceptualize sports in ways that are hardly distinguishable for the rest of mainstream America. However, I seek to highlight the many and really important ways that certain sports, which may have originated outside of Indian Country, have become indigenized by Native athletes—that is, interpreted through Indigenous values and become an intricate part of Indigenous communal life.

This process of indigenization is what most interests me, and it is for this reason that this book deals with two sports that started outside of Indian Country.

It’s inspiring to see how sports like basketball and skateboarding are becoming tools for community building and cultural revival across generations in Native communities. The idea of “skate elders” is truly a special touch!